Abstract

Despite innovative discoveries, there are challenges amidst gaps in diagnosing depression within the location selected by the doctorate candidate. Hence, in an effort to allay this finding, it is vital to initiate proper screening. Notwithstanding the acceptance that screening is a significant step towards the alleviation of treating depression, it remains uncertain what screening tool ought to be used that is most effective. Quality of standard in care planning for depression in combination with the protocol of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) can service the diagnoses and treatment tailored to an individual. The literature review provides EB analysis for the topic of depression to identify the need for an appropriate screening tool in addition to the PHQ-9 in the assessment evaluation process. An ongoing objective is to provide optimum care for depressed adults with fewer patient safety risks. This document affords an introduction to the selected topic; lists the methodology and search strategy used for the literature search; and a critical review of the literature, as well as the execution plan and a conclusion with predicted findings.

Introduction

Depression is a common serious mental health disorder that adversely impacts individual feelings, thought processes and actions. 1 in 23 Americans lives with a serious mental illness like major depression. Per year, 210.5 billion dollars is estimated as the economic burden associated with major depression. This includes missed workdays, decreased work productivity with an upsurge in medical costs (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018). The American Psychological Association [APA] (2019) is the leading authority concerning mental health matters. According to APA, depression causes loneliness, sadness, a loss of interest in activities once enjoyed and can lead to deep emotional and physical problems (APA, 2019; World Health Organization, 2020).

Depression screening is crucial for ensuring the high quality of life of patients with the disorder, but it is not easy to perform, and multiple different screening tools exist for that goal (American Psychiatric Association, 2017). As a result, figuring out the best approach to depression screening is an important clinical problem that can benefit the patients and families of different healthcare settings, including the Orlando Psychiatric clinic. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9 and PHQ-2) is among the screening tools that seem to be effective in this regard (Kamenov et al, 2017; Levis, Benedetti, & Thombs, 2019), but it is not mandated for use in the Orlando Psychiatric clinic. In this project, the usefulness of applying this tool to the context of the Orlando Psychiatric clinic is going to be investigated.

Pathophysiology of Depression

The exact etiology of depression is unknown. Depression is the most common mental health disorder. Research suggested major depressive disorder could have a substantial effect on morbidity and mortality, contributing poor outcomes, disruption of interpersonal relationships, lost time at work, substance abuse, poor health, and may lead to suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2017; Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2018). According to Fekadu et al. (2017) depression may be caused by a combination of genetic, biological, environmental, and psychological factors. The added concern references the improper functioning of the estrogen, vasopressin, thyroid hormones and chemical imbalances. With depression, there is pessimism and despondency that interferes with one’s daily life (APA, 2019). Because of all these negative effects, the timely diagnosing of depression is critical (American Psychiatric Association, 2017).

PICOT Topic Depression

The project focuses on adult people (between 18 and 65 years of age), which are the population that is most susceptible to major depressive disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In other words, the population was determined as a result of this susceptibility and also to improve the project’s feasibility and avoid recruiting children or older adults. The settings of primary care were chosen because of the specifics of the intervention.

In terms of intervention, based on the literature review (see below), a specific questionnaire (PHQ-9 ) was chosen that is used as a screening tool for depression in various settings but especially primary care (Kamenov et al, 2017; Levis et al., 2019). Furthermore, the comparison is the absence of a questionnaire, which is a not uncommon practice in healthcare (Levis et al., 2019). From the perspective of the outcome, the ability of the questionnaire to detect depression will be compared with the help of patients who will also be tested through an alternative mean such as structured interviews (Munoz-Navarro et al., 2017). In terms of time, the project will take up six weeks. The resulting PICOT question can be found below.

Among adults 18-65 years (P) can a questionnaire-screening tool for depression along with DSM-5 standard protocol of care (I) compared with not having the questionnaire ( C) assist with the accuracy of detecting depression (O) over six weeks during evaluation (T)?

Review of Evidence

A literature search was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of the PHQ-9 tool in EBP comparison and contrast to not using the PHQ-9 in clinical practice.

Selecting Screening Tools for Depression

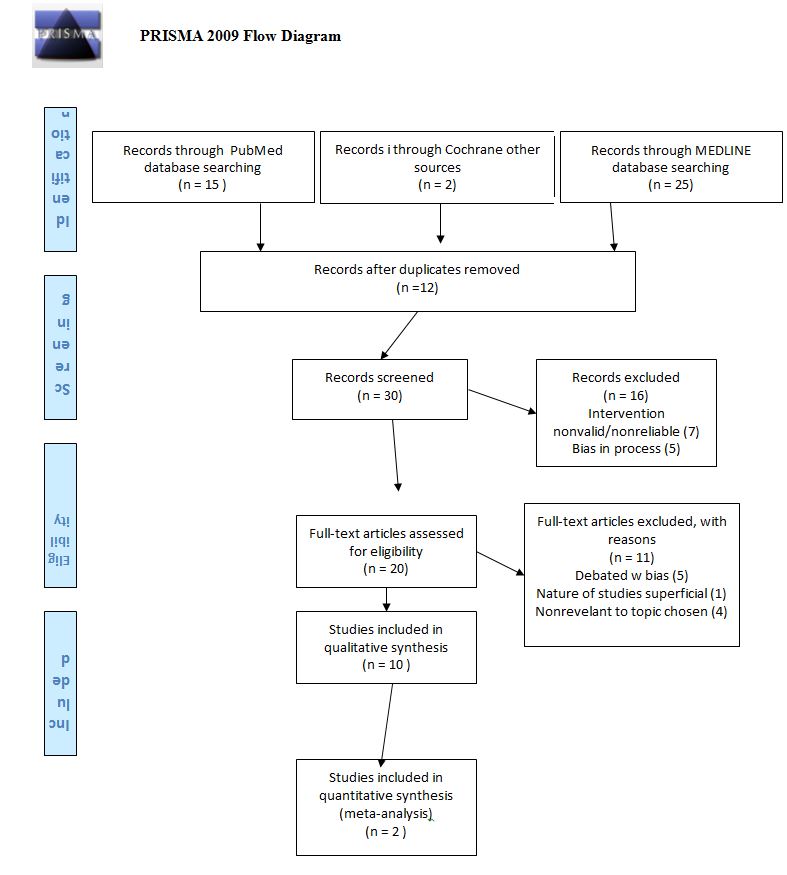

The importance of selecting an appropriate screening tool is vital and relies on a timely accurate result in diagnosing depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2017). The keywords utilized were adult depression, PHQ-9, and Major Depressive Disorder. MEDLINE, Cochrane, and PubMed were searched for systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized clinical trials (RCTs), cohort studies within association of diagnosing major depression. There were twenty-five articles reviewed of which ten were selected. The process consisted of obtaining full-text peer-reviewed articles, and filters involved evidence-based articles from 2015-2020.

The studies were evaluated with the selected inclusion and exclusion criteria in practice. These studies were researched worldwide and written in the English language. The participants reviewed in the articles were adults within primary care settings. The PRISMA flow chart is illustrated below.

Search Results

The search generated a total of 10 studies after duplicates were removed from the 20 full text articles reviewed. Among the studies, meta-analyses were included, which resulted in an increase of the literature and sample sizes explored.

Thus, Levis et al. (2019) conducted a meta-analysis that researched 58 of 72 eligible studies (N=17357; major depression cases n=2312). Combined sensitivity and specificity maximized at a cut off of 10 above among studies with a qualitative semi-structured interview (29 studies, 6725 participants, sensitivity 0.88, 95% confidence interval 0.83 to 0.92; specificity 0.85, 0.82 to 0.88). Across cut-off scores 5-15, sensitivity with semi-structured interviews was 5-22% higher than for fully structured interviews (MINI excluded; 14 studies, 7680 participants). Levis et al. (2019) concluded PHQ-9 sensitivity compared with semi-structured diagnostic interviews was greater than previous conventional meta-analyses that reference standards.

Brooke, Benedetti, and Thombs (2019) prepared a meta-analysis, a cross cut-off scores 5-15, sensitivity with semi-structured interviews was 5-22% higher than for fully structured interviews (MINI excluded; 14 studies, 7680 participants) and 2-15% higher than for the MINI (15 studies, 2952 participants). In addition, finding summarized of Level I evidence, over all author reported clinician and patient perspectives are essential for informing the context of clinical research, and overcoming the gap between clinical research and the care of individual patients. The authors concluded that greater accuracy and comprehensive evidence on the effectiveness of available interventions (questionnaire) for depression is needed to answer the steadily escalating societal and economic burden of the disease.

The systematic literature review of Kamenov et al. (2017) set in a European clinic incorporated 247 articles, including 71,904 participants. A total of 66 interventions were identified, all of them grouped into three main categories: psychotherapies (N = 22), pharmacotherapies (N = 20) or other therapies (N = 24). An expert survey was sent to clinicians as well. Of 250 practicing clinicians, with a 52% response rate, 130 clinicians from around the world filled out the survey. Of them, 95 were professionals from 21 countries in Europe, and 35 (27%) were residing outside Europe. Kamenov et al.(2017) explained results from the expert survey did not reveal major differences in the answers of European and non-European clinicians; however, these results are not generalizable due to the small number of non-European clinicians. This lack of evidence suggests that a new instrument comprehensively assessing all relevant functioning areas should be also validated in different cross-national samples. Moreover, the instrument should be sensitive to country differences and be validated in different settings. Recommendation is for more research from low-, middle-, and high-income countries is needed to provide country-specific functioning information.

Additional studies reviewed that were individually classified, performed in the United States, Canada, Peru, Spain, Europe and Africa. Villarreal-Zegarra, Lopez-Lonzoy, Bernabé-Ortiz, Melendez-Torres, and Bazo-Alvarez (2019) conducted a mixed cross-sectional longitudinal study of a valid group comparison made with the PHQ-9 of a measurement invariance study across groups by demographic characteristics of Peruvian health care. Of the population studied, participants included 30,449 subjects (56.7% of women, average age 40.5 years, age greater than 18 years (standard deviation (SD)= 16.3), lived in urban areas, 74.6 un-married, had 9 years of education on average (SD= 4.6)). Of standard CFA, one-dimensional best fit (CFI -0.936; RMSEA = 0.089; SRMR =0.039) statically. The PHQ-9 had presented adequate levels of reliability (a = 0.84) and adequate levels of specificity (>0.90); low sensitivity, between 0.39 and 0.73. The result of Villarreal-Zegarra et al. (2019) established reliability with strong rigor. The PHQ-9 displayed consistently good measurement invariance, allowing comparisons between groups by age, sex, educational level, socioeconomic status, marital status, and residential area. Measurement invariance provides confidence (reliability) that any difference between PHQ-9 one-dimension measures across these groups comes from a real difference in depressive symptomatology and not from group-specific properties of the instrument itself, strength in this study. Additionally, this evidence supported the optimal reliability of PHQ-9. This study concluded that the PHQ-9 studies dependable and can be duplicated with minimal limitation. An example of minimal limitation documented was based on the requirement delaying weeks for the evaluator intensive training in both Spanish and the English language.

Ferenchick, Ramanuj, and Pincus (2019) conducted a cross-sectional longitudinal study on Depression in Primary Care: Part 1-Screening and Diagnosis. The initial studies consisted of eight health centers providing care for a population of over 160,000 individuals. The participants were primary care attendees aged 18 years and more. Ferenchick et al. (2019) indicated the utilization of a validated version of the PHQ-9; it was distributed as an indicator for possible depression. The authors included a supplemental clinician encounter form completed by primary care clinicians. A total of 1014 participants were assessed. Primary care clinicians diagnosed 13 attendees (1.3%) with depression. The PHQ-9 prevalence of depression at a cut-off score of ten was 11.5% (n = 117), of whom 5% (n = 6/117) had received a diagnosis of depression by primary care clinicians. The data collection and data analysis were appropriate. The statistical value was represented in the population. This research demonstrated rigor, showed credibility, dependability, transferability, and feasibility in findings. Limitations were minimally identified. Ferenchick et al. (2019) noted that primary care providers play a central role in the management of depression

Ramanuj, Ferenchick, and Pincus (2019) revisited the reproducibility in a part two research. A subsequent longitudinal cross-sectional study in a primary care setting for depression was conducted. In a research-based analysis of 14 studies comprising over 5,000 participants, the PHQ-9 tool recorded 80% sensitivity at the confidence level of 95%. Statistically, the specificity stood at 92% for the confidence interval of between 88% and 95%. With minimal limitations for both studies, the consensus was that PHQ-9 satisfied the standards of a reliable and valid screening tool. Moreover, it was pointed out that the tool was in the public domain for use. Authors indicated that a meta-analysis covering 17 validation studies affirmed that the PHQ-9 tool was acceptable across various settings, populations, and countries. Authors asserted and concluded the validity of the PHQ-9 is uncontested since it was confirmed roughly 20 years ago.

Munoz-Navarro et al. (2017) conducted research of a randomized clinical trial (RCT) and utility of the PHQ-9 to identify the major depressive disorder in adult patients in Spanish primary care. The RCT was designed to evaluate, diagnose, and treat emotional disorders among primary care patients in Spain. The location was of several cities in Spain (two centers in Valencia, and one each in Albacete, Vizcaya, and Mallorca). A total of 836 participants agreed to participate and were therefore included in the baseline sample used to study the factor structure of the PHQ-9. Of these 836 patients, a subgroup of 218 participants (who were finally included in the RCT and re-evaluated with the PHQ-9 three months later) was used to assess factorial invariance over that time. A total of 178 patients completed the full PHQ test, including the depression module (PHQ-9). Also, a Spanish version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I) was implemented by clinical psychologists that were blinded to the PHQ-9 results. The psychometric properties of the PHQ-9 as a screening tool was evaluated as compared to the SCID-I as a reference standard. The statistical results calculated areas under the ROC curves for the PHQ-9 (n=172) and the PHQ-9/CA and PHQ-p/S sub-scales were 0.914, 0.924, and 0.846, correspondingly the PHQ-9 with more accuracy than the PHQ-9S (p=0.002) with no additional difference. The areas under the ROC curves of the PHQ-9 and the NDDI-E showed similar accuracy (n=127; 0.0930 vs 0.934; p=0.864).

Munoz-Navarro et al. (2017) concluded that PHQ-9 was an efficient and non-proprietary depression screening instrument for use in adults with depression in multiple medical populations. With awareness, the results concluded the most important validating efficacy of blinding, choosing outcome measurements, data collection, and accurate sample size. Authors Munoz-Navarro et al. (2019) concluded the effectiveness of the PHQ-9 as meaningful in medical advancement when screening for depression.

Fekadu et al. (2017) conducted a cross-sectional survey study in eight health primary clinics in rural Ethiopia serving over 160,000 people and using a validated version of the PHQ-9 administered as an indicator of depression. Participants were consecutive primary care attendees aged 18 years and above. A total of 1014 participants were assessed. Primary care clinicians diagnosed 13 attendees (1.3%) with depression. The PHQ9 prevalence of depression at a cut-off score of ten was 11.5% (n = 117), of whom 5% (n = 6/117) had received a diagnosis of depression by primary care clinicians. The PHQ9 prevalence of depression at a cut-off score of ten was 11.5% (n = 117), of whom 5% (n = 6/117) had received a diagnosis of depression by primary care clinicians. Attendees with higher PHQ scores and suicidal individuals were significantly more likely to receive a diagnosis of depression by clinicians. Women (n = 9/13) and participants with higher educational attainment were more likely to be diagnosed with depression, albeit non-significantly.

Denson, & Kim (2018), in a retrospective electronic chart review study of adults in the primary clinic, intended to identify potential gaps in the management of depression and assess the perception of primary care. The population included patients 18 or greater in years of age seen in primary care clinics in Los Angeles County with a documented annual health screening (AHS) conducted between January 1, 2015, through December 31, 2015. Of the patients who received an AHS (n = 6797), 63% received PHQ assessments. Of 145 individuals with a positive PHQ-2, 69% had a positive PHQ-9. Primary outcomes were the number and percentage of patients screened for depression with patient health questionnaire (PHQ) assessments, positive depression screenings, and interventions made for positive depression screenings. Secondary outcomes were PCPs’ perceptions of the management of depression, the use of AHS, and roles for psychiatric pharmacists through evaluation of the provider survey

Kroenke et al. (2016) conducted an RCT study measured and compared outcomes with PHQ Scale: Initial Validation in three clinical trials that exhibited Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale (PHQ-ADS). RCT combines the nine-item PHQ-9 and seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale-as a composite measure of depression and anxiety within an oncology clinic. Baseline data from 896 patients enrolled in two primary-care based trials of chronic pain and one oncology-practice-based trial of depression and pain were analyzed (Kroenke et al., 2016). PHQ-ADS statistic scores can range from 0 to 48 with higher scores indicating more severe depression/anxiety), and the estimated standard error of measurement was approximately 3 to 4 points. The PHQ-ADS showed strong convergent (most correlations, 0.7-0.8 range) and construct (most correlations, 0.4-0.6 range) validity when examining its association with other mental health, quality of life, and disability measures. PHQ-ADS cut points of 10, 20, and 30 indicated mild, moderate, and severe levels of depression/anxiety, respectively. Bi-factorial analysis showed sufficient dimensionality of the PHQ-ADS score. PHQ-ADS change scores at 3 months differentiated (p <.0001) between subjects that were classified as inferior

Strength and Limitations of Evidence

The selected articles included 3 Level I sources, 2 Level II sources, and 1 Level IV sources according to Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt’s (2019) levels of evidence. Level of Evidence for the research articles are listed in the table of sources below.

The individual studies reviewed using the criteria for evaluation of the level of evidence in design by Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2019). The systematic reviews of cohort studies belong to the category of level IV evidence based on Melnyk and Fineout-Overholt (2019). The strength of the systematic review of cohort studies is within use of primary data having a high level of evidence. In addition, the cohort studies were evaluated using criteria for evidence-based evaluation of this design. The weakness of the systematic review of cohort studies is the high risk for bias introduced by the selection of sample and the data analysis tool

Screening tool accuracy

The process identified in the meta-analysis, systematic review, RCT and cohort studies utilized PHQ2 and PHQ9. The evaluation of screening tool was based on specificity, sensitivity and other statistical analysis methods. However, a section of studies failed to report tool sensitivity and specificity. The values were assessed to determine favorable high accuracy. Brooke et al. (2019), Levis et al. (2019), Kamenov et al. (2017), examined PHQ-2 and PHQ-9 use in the assessment of major depressive disorder. The PHQ-9 screening tool was assessed by Munoz-Nevarro et al. (2017), Korenke et al. (2016), Villarreal-Zegarraet et al. (2019); The cohort studies of Ferencheck et al. (2019), Fekadu et al. (2017), Danson, & Kim (2018) studies utilized a two-step approach.

Final Outcome

The discussed studies established PHQ-9 reliability with strong rigor. The PHQ-9 displayed consistently good measurement invariance, allowing comparisons between groups by age, sex, educational level, socioeconomic status, marital status, and residence area (Villarreal-Zegarra et al., 2019). Measurement invariance provides confidence (reliability) that any difference between PHQ-9 one-dimension measures across these groups comes from a real difference in depressive symptomatology and not from group-specific properties of the instrument itself. Additionally, the evidence supported the optimal reliability of PHQ-9. This study concluded that the PHQ-9 studies dependable and can be duplicated with minimal limitation.

Ferenchick et al. (2019) in both studies regarded it with a minute limitation for both studies and a consensus that the PHQ-9 satisfied the standards of a reliable and valid screening tool. Moreover, the tool is in the public domain for use. Authors indicated that a meta-analysis covering 17 validation studies affirmed that the PHQ-9 tool is acceptable across various settings, populations, and countries. Authors asserted and concluded the validity of the PHQ-9 is uncontested since it was confirmed roughly 20 years ago Both studies conducted for part-1 and part-2 supported evidence-based research, which is transferable as the PHQ-9 is practical and demonstrated reliability for primary care clinical practice.

Results of the studies conducted by Munoz-Navarro et al. (2017) validated that the PHQ-9 is an efficient and nonproprietary depression screening instrument for use in adults with depression in multiple medical populations. With awareness, the results concluded the most important validating efficacy of blinding, choosing outcome measurements, and an accurate sample size.

Munoz-Navarro et al. concluded the effectiveness of the PHQ-9 is meaningful in medical advancement when screening for depression. The PHQ-ADS showed strong convergent (most correlations, 0.7-0.8 range) and construct (most correlations, 0.4-0.6 range) validity when examining its association with other mental health, quality of life, and disability measures. The research by Kroenke et al. (2016) concluded that PHQ-ADS maybe a reliable and valid composite measure of depression and anxiety which, if validated in other populations, could be useful as a single measure for jointly assessing two of the most common psychological conditions in clinical practice and research.

Brooke et al. (2019) reported that specificity was similar across diagnostic interviews. A cut-off score of 10 or above maximized combined sensitivity and specificity overall and for subgroups. In regard to rigor, the PHQ-9 seemed to be similarly sensitive, but limitation perhaps is less specific for younger patients than for older patients. There is a cut-off score of 10 or above can be used regardless of age. The research concluded that PHQ-9 sensitivity compared with semi-structured diagnostic interviews was greater than in previous conventional meta-analyses that combined reference standards. The use of PHQ-9 demonstrated effective satisfaction. Based on empirical research findings, gaps in the management of depression were identified.

Denson and Kim (2018) reported although depression screenings were performed for the majority of individuals receiving an AHS, no documented interventions were made for most of those individuals who screened positive for depression. Greater than 50% of individuals with a positive PHQ-9 had no preexisting depression diagnosis. Seventy-six percent of individuals with a positive PHQ-9 and 78% with reported suicide ideation had no documented intervention. The limitation was that the intervention was not documented. Although depression screenings were performed for the majority of individuals receiving an AHS, no documented interventions were made for most of those individuals who screened positive for depression. The majority of providers reported there is a role for psychiatric pharmacists in primary care. Primary care clinics could benefit from psychiatric pharmacist involvement in depression screening and follow-up processes.

Application to Practice

Levis et al. (2019) utilized a meta-analysis to determine the accuracy of PHQ-9 for screening accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression. Kamenov et al. (2017) concluded in the studies that a personalized approach in treatment decision-making better measurement will facilitate clinical decision making and answer the escalating burden of depression. Fedaku et al. concluded, although not based on a gold standard diagnosis, that over 98% of cases with PHQ-9 depression were undetected. Failure to the recognition of depression may pose a serious threat to the scale-up of mental healthcare in low-income countries (American Psychiatric Association, 2017). Addressing this threat should be an urgent priority, and requires a better understanding of the nature of depression and its presentation in rural low-income primary care settings.

The PHQ-9 tool reliability was captured and was significant in the literature research validation that demonstrated efficacy in overall effectiveness mostly in primary clinical setting. The robust studies expounded that the PHQ-9 is most effective tailored to patients when screening for depression. There were minor limitations unavoidable central to patient personal issues. The conclusion of the literature purposed there is compelling evident that implementing the PHQ-9 tool along with the protocol of the DSM-5 for depression is a valid and reliable tool. PHQ-9 would benefit patient diagnosis for depression by healthcare professionals in the primary clinical setting.

Thus, for this research, the problem is identified as the screening of depression in primary care. The stakeholders are recognized to be internal and external; specifically, the healthcare professionals and other staff of primary care settings and patients with their families are the primary stakeholders. The literature search was conducted in regard to the screening tools utilized in diagnosing depression. The research suggested that there is a variation with the screening tools’ when comparing for accuracy, but PHQ-9 is shown to be an effective screening tool for detecting depression in adults within primary care settings. The utilization of most effective screening tools will decrease errors in diagnosing depression in the primary care settings and lighten the burden of higher healthcare cost that is associated with the mis-diagnosing depression (American Psychiatric Association, 2017), which calls for the development of the proposed research.

The Change Model

The evidence-based practice (EBP) theory selected for this project is the IOWA change model. The IOWA model is a guideline to assist providers, nurses, and supporting staff members to make clinical decisions in regards to clinical and managerial practices that affect patient outcomes (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019). The fundament of IOWA theory is based on scientific processes for problem-solving. It prioritizes patient safety, quality care, nursing care directives, decreases suffering, and is pertinent to quality, cost, and access of care. The application of this model is based on the underpinning of promoting standards in quality care for best practices. It is a seven-point process.

- Identify triggers, encourage nurses and clinical healthcare staff to identify problems, concerns, or questions.

- Clinical applications, having the ability to pinpoint imperative and clinically relevant medical practice questions that can be addressed through the EBP process.

- Organizational priorities, having the ability to decipher the order of importance of the clinical issue when assessing the need to complete the EBP projects.

- Forming a team that would initiate, implement, and facilitate the EBP change.

- Piloting a practice change, having the ability to calculate and plan the implementation and evaluation of the process.

- Evaluating the pilot by assessing the appropriateness of the beginning and the ending of the process.

- Evaluating practice change by assessing improvements, evaluating trends, and outcomes (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019, p. 395).

The key points are emphasized on critically appraising and judging the strength of the evidence, synthesizing the evidence and assessing the feasibility, benefits, and risk of implementing it in the practice (Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2019).

Change Model & Application to Practice

There are other methods and screening tools utilized in diagnosing depression. However, there are innumerable and may not present benefits in sensitivity and specificity or may not be tailored to be beneficial for the individual. In other words, there is variation in comparison to the screening tools’ accuracy. The study has demonstrated that PHQ-9 and PHQ-2 have better screening accuracy compared to not using the screening tool. The related result provides evidence for healthcare professionals and nurses to develop a consensus on the most effective screening approach for detecting depression in adults in primary care settings to improve best practice outcomes.

Iowa Model Topic & Problem

PICOT

Among adults 18-65 years (P) can a questionnaire-screening tool for depression (PHQ-9) along with DSM-5 standard protocol of care (I) compared with not having the questionnaire ( C) assist with the accuracy of detecting depression (O) over six weeks during evaluation (T).

Implementing the Model Process

In the greater Orlando Psychiatric clinic, the IOWA model technique will be implemented as was agreed upon by the medical director. While the issue is already identified, it can be suggested that more information about depression screening in the clinic takes place for the first stage of the process. Additional concerns may be found as a result. Similarly, while the decision on the EBP has been made, more research on the topic would be a helpful second step, as well as the prioritization of clinical issues (third step). As a fourth step, the team that will be implementing the change will be created, and as the fifth step, the change will be piloted as discussed below. The pilot will then be evaluated, but the final step would be reserved for another research.

Interdisciplinary and professional involvement will be necessary for topic discussion and resource personnel. It will ensure effective management of quality, safety, efficacy, bringing the project to a conclusion. In order for the success of adopting the change process, there will be evaluated within the risk management assessment for two basic activities to occur simultaneously evaluating strength, weakness, opportunities, threats, SWOT, and gap analysis (Harrison, Noel-Storr, Demeyere, Reynish, & Quinn, 2016). These tools will assist in determining the relevant outcomes of the project and its potential for ensuring EBP change.

Action Plan/Method for Measuring Outcomes

The proposed site of project is the Orlando Psychiatric clinic. Currently, it is known that the chair is Dr. Jennifer Serotta, but the co-chair and mentor are to be announced. The project will run over a period of six weeks to determine during the evaluation process can the PHQ-2 and the PHQ-9 along with the DSM-5 standard protocol of care compared with none assist in the accuracy of detecting depression. The medical assistant will check in the patient and with the page application of the screening tool applied to be recorded. A practice site manager will recruit patients according to diagnosis and criteria related to depression. The PHQ-2/PHQ-9 questionnaire will be added to the interview process for evaluation in the intervention group, but it will not be added for control group evaluation (two practitioners) during a trial of six weeks. During the six-week period, there will be a documented tracking system of the questions and selected patients with a diagnosis of depression in the clinical setting as a method of control and measurement.

The provider (NP, Physician, PA) serves as the clinical expert, utilizes the diagnosis screening process, along with the tailored treatment plan and patient education. The provider in primary care serves as the EBP preceptor, noting tools, timeline, and appropriate treatment plan. Over a 6-week timeframe, there will be a measurement of the total number of subjects, use of the screening tool implantation, topic guided selection (outcomes). Additionally, the patients will be evaluated for the signs of depression with a structured interview, and the results of PHQ-9 will be compared to the results of the structured interviews to determine the effectiveness of the former with the help of inferential statistics for statistically significant differences (Munoz-Navarro et al., 2017); the specific statistical test will depend on the characteristics of the data. An approximate timeline of the project is presented below (Zaccagnini & Pechacek, 2019).

Conclusion: Prediction of Findings and Summary

It is difficult to predict all the outcomes, but the following suggestions can be made based on the literature review. Most likely, the participants will be taking care to apply the PHQ-9 to the intervention group, and most probably, the number of patients in both groups is not going to differ by much. The number of people with depression cannot be predicted, but in terms of the PHQ-9 comparison to structured interviews, the two tools seem to support each other’s validity (Munoz-Navarro et al., 2017). As a result of the project, the effectiveness of PHQ-9 as a primary care depression screening tool will be further supported and, more importantly, the project site will have adopted it, improving its ability to screen patients for depression. Additionally, the research will provide an example of an IOWA-model EBP project, and its longitudinal effects can become another topic for a future research. Thus, the project is important for EBP, and it can be feasibly carried out.

Indeed, the proposed study is very feasible because of its similarity to other research that focused on the same topic of PHQ-9 usability (Levis et al., 2019; Munoz-Navarro et al., 2017). Specifically, the project will involve an IOWA-based EBP with a focus on the comparison of PHQ-9 to no questionnaire within the Orlando Psychiatric clinic that will take six weeks and will involve adults. By screening the intervention group with PHQ-9 and comparing the results to those of the control group, the project will be able to demonstrate the relative efficacy of both options and promote the use of an EBP tool in the Orlando Psychiatric clinic, potentially improving its ability to screen for depression.

References

American Psychological Association. (2019). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th Ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder (5th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing.

American Psychiatric Association. (2017). Depression screening rates in primary care remain low. Web.

Brooke, L., Benedetti, A., & Thombs, B.D., (2019). Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. (2019). BMJ, 365(1476), 1781.

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2018). Mental health. Web.

Denson, B., & Kim, R. (2018). Evaluation of provider response to positive depression screenings and physician attitudes on integrating psychiatric pharmacist services in primary care settings. Mental Health Clinician, 8(1), 28-32.

Fekadu, A., Medhin, G., Selamu, M., Giorgis, T. W., Lund, C., Alem, A.,… Hanlon, C. (2017). Recognition of depression by primary care clinicians in rural Ethiopia. BMC Family Practice, 18(1).

Ferenchick, E., Ramanuj, P., & Pincus, H. (2019). Depression in primary care: part 1—screening and diagnosis. BMJ, 365(1794), l794.

Ramanuj, P., Ferenchick, E., & Pincus, H. (2019). Depression in primary care: part 2—management. BMJ, 365(1835), l835.

Harrison, J., Noel-Storr, A., Demeyere, N., Reynish, E., & Quinn, T. (2016). Outcomes measures in a decade of dementia and mild cognitive impairment trials. Alzheimer’s Research & Therapy, 8(1), 1-10.

Kamenov, K., Cabello, M., Nieto, M., Bernard, R., Kohls, E., Rummel-Kluge, C., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. (2017). Research recommendations for improving measurement of treatment effectiveness in depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(356), 1-9.

Kroenke, K., Wu, J., Yu, Z., Bair, M.J., Kean, J., Stump, T., & Monahan, P.O. (2016). Patient Health Questionnaire Anxiety and Depression Scale: Initial validation in three clinical trials. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(6), 716-727.

Levis, B., Benedetti, A., & Thombs, B.D. (2019). Accuracy of Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for screening to detect major depression: individual participant data meta-analysis. BMJ, 365, 1781.

Melnyk, B. M., & Fineout-Overholt, E. (2019). Evidence-based practice in nursing & healthcare: A guide to best practice. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Muñoz-Navarro, R., Cano-Vindel, A., Medrano, L. A., Schmitz, F., Ruiz-Rodríguez, P., Abellán-Maeso, C.,… Hermosilla-Pasamar, A. M. (2017). Utility of the PHQ-9 to identify major depressive disorder in adult patients in Spanish primary care centres. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 291.

Villarreal-Zegarra, D., Copez-Lonzoy, A., Bernabé-Ortiz, A., Melendez-Torres, G., & Bazo-Alvarez, J. (2019). Valid group comparisons can be made with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9): A measurement invariance study across groups by demographic characteristics. PLOS ONE, 14(9), e0221717.

World Health Organization (2020). Depression. Web.

Zaccagnini, M., & Pechacek, J. M. (2019). The doctor of nursing practice essentials: A new model for advanced practice nursing. New York, NY: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Appendix A

Table of Evidence