Introduction

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD), like all personality disorders represents a stable, pervasive pattern of behavior that is present for an individual’s entire life. In generally, the configuration is primarily one of a disregard for, and a violation of, the rights of others. This manifests itself in the individual fundamentally not caring about the wants, needs, and desires of others. The result of this core belief that others do not matter is behavior that frequently leads to arrest for petty offenses like theft. Though these crimes are not personality traits, the record that they create is reliable and traceable, making a good diagnostic tool. Another similar diagnostic tool is the individual’s work and school record. ASPD traits make listening to authority figures nearly impossible so most of these individuals have spotty educational and work histories.

These behavioral markers are the result of several personality traits. One of these chief characteristics is impulsiveness. Individuals with ASPD do not stop to carefully consider the consequences of their activity, rather they simply do what they want for themselves in the moment. This impulsivity can lead to reckless and dangerous activity both for their own safety and for the safety of others. They may drive with excessive speed or push others near a traffic filled intersection. If they desire the property of others and they can take it, they will. This same attitude that is used toward property is used toward other people. They will lie or con others in order to fulfill their personal desires.

If the individual with ASPD is not able to meet their desires through theft or con, they will not stop trying to fulfill their needs. They are prone to get very irritable and often get very aggressive towards others. Fighting with others will likely be prevalent in their personal history. At the end of their theft, maltreatment, and aggressiveness they will not feel sorry for their actions. They will either not care that they have caused harm or rationalize the situation.

In order to qualify for a diagnosis three other criteria must be met:

- The individual must be at least 18 years old. Individuals who are growing up and going through puberty do not have the stable personality required to be diagnosed with a personality disorder.

- There must also be proof in their developmental history that the individual had antisocial traits as a child. This is demonstrated by fulfilling criteria for Conduct Disorder before age 15. Diagnosticians want to know that the individual’s personality has been set. They would like to know that the individual was like this before puberty and will be like this long after puberty before diagnosing a personality disorder.

- The antisocial behavior must not be exclusively during schizophrenia or a manic episode. The behavior should not be because of an Axis I condition.

Psychopathy & Sociopathy

In the literature there is a much greater emphasis on studying psychopathy and sociopathy than there is antisocial personality disorder. These three are related but are not identical. Antisocial personality disorder is the only one of these three terms that exists in the DSM-IV-TR. Psychopathy is defined by characteristics such as a lack of empathy and remorse, criminality, antisocial behavior, egocentricity, manipulativeness, irresponsibility and a parasitic lifestyle. It is commonly conceptualized that psychopathy is a more severe form of ASPD and this thinking is reasonably accurate. Almost all individuals who fulfill the requirements to receive the label of psychopathy fulfill the requirements for ASPD but most of the individuals who fulfill the requirements of ASPD do not also get the label of psychopath. The term sociopath is an attempt to demystify the term psychopath since many generalize the term psycho in psychopath to apply to other terms like psychotic. Sociopathy is also an attempt by some clinicians to explain the etiology of the condition as characterized by early socialization experiences.

Subtypes

One of the diagnostic challenges with any personality disorder is that there is typically significant overlap between the personality disorders. This is due both to the diagnostic overlap in the definition of each of the personality disorders and the fact that individuals typically display many different traits throughout their lifetime. In order to get a better understanding of the common personality trait overlaps, Theodore Miller created a series of 5 subtypes of ASPD:

Subtypes of ASPD

Coveteus—this type is purely made up of ASPD traits. This individual feels intentionally denied and deprived and seeks to get the things s/he covets but gets little satisfaction from ownership.

Nomadic—this type is ASPD with schizoid, schizotypal and avoidant features. This individual feels cast aside and is typically a drifter and societal dropout. When this individual acts out it is against that impulse.

Malevolent—this type is a mix of ASPD with paranoid personality features. This individual is typically more violent than the other personality disorder types. He expects betrayal and punishment and attempts to get revenge in a pre-emptive manner.

Risk-taking—this type is a mix of ASPD and histrionic features. This individual has the risk taking features of ASPD amplified heavily. They are very audacious and bold to the point of recklessness and they continuously pursue perilous adventures.

Reputation-defending—this type is a mix between ASPD and narcissistic features. This individual has a need to be thought of as unflawed and formidable and will react extremely negatively to perceived slights to status.

Differences

Two of the most difficult differences for ASPD are Narcissistic and Histrionic personality disorder. Narcissistic Personality Disorder shows similar distorted thinking about others. They care little for the wants and needs of others and have limited empathy. Individuals with Narcissistic PD can be manipulative as well. However, Narcissistic individuals rarely show evidence of conduct disorder in youth or antisocial aggression. The underlying thought process behind their rules and norms breaking behavior is different as well. With ASPD the individual feels that they are entitled and special and that they can break the rules because of this fact. The ASPD individual does not need the rationalization, typically they do what they want because they want to do it.

Individuals with Histrionic PD are often impulsive, show very little depth in their empathy and understanding of others. Their dramatic flair can be seen as impulsivity and can do things like maintaining affairs that can be characterized as violating social norms. However, histrionic individuals are not aggressive and will not show evidence of Conduct Disorder in typical presentation.

Etiology

The nature of personality disorders makes their etiology more problematic to pin down than other disorders. ASPD requires even more evidence of prolonged atypical functioning than other personality disorders because it requires evidence of maladaptive functioning before age 18. This requirement muddies the already murky waters that are the interplay of genetics and environment and their expression in both brain anatomy and psychological activity.

Irregularities of the serotonin network in the brain responsible for the release, use, and reuptake of the neurotransmitter are linked to individuals with ASPD. This network has been linked separately both to individuals diagnosed with ASPD and to highly impulsive behavior. The theory is that this deficit can lead either to arousal thresholds being too low in individuals who show impulsivity or the arousal threshold is too high in individuals who are cold or callous.

Psychological and family systems factors have also been shown to have an effect on the expression of ASPD. The researchers used national epidemiological survey and found individuals from a data set of alcohol users who also were antisocial, finding 1200 individuals on which to base their results. They found that significant childhood experiences of abuse and neglect significantly predict eventual display of ASPD. These early experiences of violence or abandonment have significant effects on attachment and relationship formation.

Duggan (Duggan, Howard, Khalifa, & Lumsden, 2012) showed a positive relationship between early onset of alcohol use and the transition of conduct disorder to ASPD. Those who used alcohol and other substances at an earlier age more often wound up being diagnosed with ASPD than those who did not. This effect can easily by hypothesized to have an etiological function in either biological or social bases. Perhaps the drug use affected neurological pathways to make the individuals more susceptible. Perhaps early onset drug use was indicative of a social network that was more conducive to reinforcing antisocial behavior.

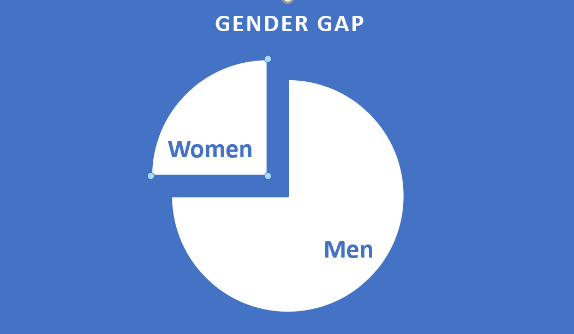

Gender Gap

There is a very wide disparity between the number of men and women who meet the criteria for diagnosis with ASPD. Epidemiological research suggests that as many as 3% of men have ASPD while less than 1% of women do. Some theorists, like Miller, have argued that the disparity in men and women in ASPD is mirrored by the same disparity with the diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder. Women are proportionately more likely to receive that diagnosis than men are to receive a diagnosis of ASPD. This may be due to the fact that the criteria for ASPD are heavily gender biased. Where men will use naked aggression in a way that leads to multiple arrests (criteria A-1 and criterion A-4) women tend to use relational aggression which has very different outcomes. The same underlying etiology and pathology lead to very different behaviors because these behaviors are mediated by cultural norms. The masculine ideal in the United States contains many antisocial traits. Men are encouraged to be self-reliant, independent, and to use physical force when necessary. They are taught to be stoic and unemotional. This antisocial personality is an overextension of that ideal. Women, on the other hand, are not taught to be unemotional or physically violent, so they manifest that same aggression in different ways. Alegria (Alegria, et al., 2013) found that women have to have a significantly higher lifetime loading of abuse and neglect to show antisocial traits than men do.

The top theoretical explanations for antisocial personality traits unfortunately leave little for individual agency. The difficulty is that the diagnosis of ASPD requires that the individual gain their personality traits when they are least able to defend against them – during or before their teen years. The biological explanation leaves basically no room for personal agency. It is impossible to willfully change your brain chemistry. Other theoretical standpoints argue that childhood maltreatment and neglect are to blame. A neglected or abused child has little ability to even avoid their maltreatment, let alone recover from their own psychological load. One simple step that is clear from the literature is to delay the onset of alcohol and substance use. Using substances at an early age is a significant loading factor for ASPD. Avoiding early alcohol use can positively affect brain chemistry and alter future habitual activity for the better (Duggan, Howard, Khalifa, & Lumsden, 2012).

Hypothetical Conceptualization

Psychodynamic

Psychodynamic theorists conceptualize ASPD begins in the early childhood phase of trust vs. mistrust. Children who will later show evidence of conduct disorder and then ASPD do not have adequate social relationships as children. These inadequate relationships center on a lack of parental love. A lack of parental love can lead a child in many different pathological directions and is not necessarily indicative of ASPD in and of itself. Some subset of these children respond to the lack of love demonstrated by their parents by becoming emotionally aloof. They begin to develop the relational style that they are taught at home by bonding with others through overt power dynamics instead of a shared emotional bond. Psychodynamic theorists can point to the evidence of pervasive early childhood trauma in individuals who eventually develop ASPD as proof of their conceptual framework.

Unfortunately, psychodynamic theoretical framework is largely ineffective (Gibson, 2019). There are a number of hypothesized reasons for this therapeutic failure. The first is that almost no one with ASPD is in treatment voluntarily (Persons getting therapy by the order of the court system have little incentive to change). In addition to this difficulty, individuals with ASPD also have no conscience and little motivation to change who they are naturally which further compounds treatment difficulty. Antisocial individuals also tend to have a very low frustration tolerance which makes seeing treatment through to its conclusion very difficult.

Cognitive-Behavioral

Cognitive-behavioral therapists do not attempt to repair the causes of ASPD, consistent with their treatment modalities. They target problem behavior. Therapists attempt to give ASPD individuals skills to understand moral issues and conceptualize the needs of others. Some prisons and hospitals have tried to put ASPD individuals in group settings to teach responsibility. This approach does not seem to have any effect in most cases. (Arntz, Cima, & Lobbestael, 2013)

Cognitive-Behavioral therapists conceptualize antisocial activity as a modeled behavior. Children may be reenacting the violent behavior that they experience in a far too personal manner. Theorists also believe that the negative acting out and violent behaviors may be reinforced by the attention that they receive. Parents may give in to violent outbursts simply to restore the peace once individuals have acted out.

Biological Theories

Biological theorists have begun using psychotropic medications on individuals with ASPD. Atypical Antipsychotic drugs have been used to treat ASPD. These newer antipsychotic medications bind to multiple dopamine receptor but also have an effect on serotonin. These therapies have not been evaluated in large scale trials to date. (Brook & Kosson, 2013)

Biological models have many findings pertinent to individuals with ASPD. First, as was stated in depth earlier, serotonin deficits may be responsible for ASPD traits, especially in individuals who display highly impulsive behavior. Another area of research is the frontal lobes. Many individuals with ASPD have smaller or deficient frontal lobes. Lastly, it appears that many individuals with ASPD have very low resting levels of anxiety. Low levels of anxiety explain why it is difficult for individuals to learn from past negative experiences. (Boccaccini, Hawes, Murrie, & Rufino, 2012)The biological model theorizes multiple etiologies for these deficiencies. They may come from genetic factors that cause malformation as children, nutritional deficiencies at key periods in development, the effect of viruses, or from physical harm such as brain lesions.

Conclusion

Antisocial Personality Disorder is a difficult but influential disorder. It is an important problem both for the psychological community and for society. The psychological community has not been able to offer any meaningful therapeutic approaches. Part of the reason that this is the case has to do with the very recalcitrant nature of the disorder itself. Another significant part of that reason is that the psychological community cannot decide where to focus its research. Many very distinguished individuals have been trying to dissect a tiny subset of the ASPD population because they are very scary and are good for getting grant money. Society at large has a vested interest in ASPD because it makes up such a significant portion of the prison population. These individuals are likely to recidivate and likely to commit violent crimes. Understanding this population better is vital for long term meaningful prison reform. (Lewis, Olver, & Wong, 2013)

In addition to failing individuals with ASPD in terms of treatment, it is relevant to note that society is failing individuals with ASPD in their formative years. Recurrent episodes of neglect and abuse are run-of-the-mill for individuals with ASPD. Society at large needs to do a better job of policing this kind of abuse and neglect and provide safe, rehabilitative experiences for those who are victims of it.

References

Alegria, A., Blanco, C., Petry, N., Skodol, A., Liu, S., Grant, B., & Hasin, D. (2013). Sex Differences in Antisocial Personality Disorder: Results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 1037.

Arntz, A., Cima, M., & Lobbestael, J. (2013). The Relationship Between Adult Reactive and Proactive Aggression, Hostile Interpretation Bias and Antisocial Personality Disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 53-66.

Boccaccini, M., Hawes, S., Murrie, D., & Rufino, K. (2012). When Experts Disagreed, Who Was Correct? A Comparison of PCL-R Scores From Independent Raters and Opposing Forensic Experts. Law and Human Behavior, 527-537.

Brook, M., & Kosson, D. (2013). Impaired Cognitive Empathy in Criminal Psychopathy: Evidence From a Laboratory Measure of Empathetic Accuracy. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 156-166.

Duggan, C., Howard, R., Khalifa, N., & Lumsden, J. (2012). The Relationship Between Childhood Conduct Disorder and Adult Antisocial Behavior is Partially Mediated by Early-Onset Alcohol Abuse. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 423-432.

Gibson, M. (2019). New Therapies: Treatment of Psychopathy. Sociology Journal, 325-338.

Lewis, K., Olver, M., & Wong, S. (2013). Risk Reduction Treatment of High-Risk Psychopathic Offenders: The Relationship of Psychopathy and Treatment Change to Violent Recidivism. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 160-167.