Introduction

Children with autism have difficulty communicating but only to those who do not know their complicated situation. Ordinary people who do not know autism think and believe the many myths surrounding autism. But these are myths that people with autism themselves would like to prove wrong.

We lack understanding and knowledge of autism. It is difficult to understand autistic children if we do not know how and why they are. We have to understand the way they act and speak their language.

This paper may find it very difficult to find the meaning behind the children’s characteristics and behavior if we don’t study the various literature on the subject of autism and children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. We must live with them and consult the experts including their families.

This is an attempt therefore to enter the unique world of children with ASD. People who have lived with and studied children with this phenomenon say it is not so easy to judge that someone with characteristics of ASD is an ASD. Their characteristics and behavior have to be studied.

Likewise, it is not so easy to be talking about speech-language disorders of children with autism/ASD without discussing the characteristics and behavior of the children. This subject is a broad topic that encompasses vast literature on children with ASD.

Gradin (2006), quoting Dr. Eric Courchesne and Dr. Nancy Minshew, says that autism is a disorder of the connections between different brain systems, the reason why autism/Asperger spectrum is so variable. They can vary from a genius like Einstein to a person who has epilepsy and no speech. The brain is likened to a big corporate office building with many different departments. In children with ASD, some connections between departments are missing.

Sensation, that is, from what we can see, hear, feel, smell, and taste, gives us information about the world around us. The complexity of our nervous system is quite abstract. For normal people, understanding all these seem not quite easy; thus, it is difficult for children with abnormalities in the way they feel, hear, touch, and smell. (Myles et al, 2000).

Objective

It is the objective of this essay to present in a clear manner the realities of autism and how children with ASD live and cope with their situation. We will focus on their communication and language disorders and other disabilities. A discussion will have to be provided on how they are coping.

Other topics of interest are the therapies and solutions the experts along with their families have instituted to provide children with ASD ease and comfort in life and allow them to live as normally as possible.

Guiding Research Question: How can we effectively teach children with autism?

This guiding question will be the main point in pursuing the research as this will require answers and lead to other questions like what are the methods and methodologies of teaching children with autism. What are the effective means of teaching children with autism? Who should teach children with autism? What are the proper training methods teachers assigned with teaching autistic children should have?

Along this line, we have to provide the various problems involving social and communication problems or disabilities that characterize children with autism. As we have known from the literature that autistic children have comprehension deficits, and their communication process is different from the rest of the children. Their way of social interaction is different from the rest. They cannot easily assert themselves and their way of understanding deviates from the normal course.

Diagnosis of children with autism will come from the designated physicians who are in the proper position to diagnose children with autism. The physician may be a school physician or someone authorized by the local government to do so. Most probably, an enrollee of the school will be accompanied by the parents of a prospective child with autism.

Teaching children with autism is no easy job. This requires a lot of studies and experience to be able to effectively impart in them the necessary knowledge that can help them cope with the realities of life as they grow and reach adulthood.

This study will use qualitative research. Qualitative research will provide a necessary experience for the teaching of autistic children. It is in this process where I can truly grasp the teaching experience and acquire from this experience knowing that will be valuable in the future in the teaching of autistic experience. Through this method, the right attitude and proper ways of teaching autistic children will be attained.

The point is how to be able to attain a proper and effective method of instruction for children with autism. As we have gathered from the literature, these children have their own peculiar way of communicating. They get easily distracted by our ordinary way of communicating and learning with non-autistic children. In other words, the method must divert from the common method of teaching and learning.

In the qualitative method, we will select a class of autistic children in a common local school, the choice of the school will have to be decided later as we have to find out which among the local schools do have the required population for this study. At this point, we will have to ascertain first the exact number of the population of autistic children, but when we are able to attain the number, we will adjust other programmes and schedules for the research. And once we are certain of the number of autistic children, we are going to request the school of the planned research study on autism.

Careful planning of the activities will be provided. First is the letter request to the school principal to observe the class of autistic children. This will be followed by close coordination with the teacher or teachers of the autistic children, as soon as the request is approved. While in the process of observing, if no problems are encountered, another formal letter request to research autistic children will be provided.

The request will state the purpose of the research, the duration, the process of research, the ethical dimensions, the participants who are autistic children, and other relevant information and activities to be done.

It has to be stated clearly in the letter request that the research has the purpose of acquiring data and knowledge on how to effectively teach children with autism. Observations will be conducted on a few sessions, and thereafter this researcher will actively participate in the teaching method without distracting the normal flow of activities in the learning process.

The teacher/s and parents will be informed of the study and briefed accordingly. Their consent, suggestions, ideas, and opinions are very relevant and will become a part of the research and will also be inputted in the database for the study.

We will explain to the parents the purpose of our study: that our goal is to acquire data on the proper and effective method of teaching, including the tools and materials in the proper teaching of autistic children. We will also explain that the study will be conducted in a way that the rights of the children and the parents will be protected. We will ask the teacher/s and parents to introduce us to the students to make us a part of the learning process of the children and to allow them to ‘feel at home’ with this researcher.

During our observations, we will take notes on the proper behavior of autistic children. Other important activities include the taking down of data on the demographic profile of the children, family background, age, years in school, and so forth. The teacher’s information and inputs will include their experience in teaching autistic children, their method of teaching and how they acquired such method, how effective are their methods, and the children’s progress in school, and how they react to the method of teaching. Is it effective? Information conversations with the teacher/s and parents will be a part of the study.

The research will be composed of two phases: first, the observation phase, and second, involving ourselves in the teaching and learning process. This means we will observe first how things are going on and how the children are responding to the method of teaching. Then, after a few weeks, we will suggest some proper ways out of our own observation and from the literature that we have gathered in the study of autistic children.

We will include some technological applications such as taking videos of the learning process of the research. But the recording will be done with the approval of the school authorities, the teachers, and the parents of the students. It will also be done in such a way that it will not distract the attention of the children, or the camera will be hidden.

One of the aims is to discover other ways and methods of dealing with and teaching autistic children. Some interviews will be done with the children, but the questions will have to be formulated in such a way that they will not be distracted or that they will not notice that they are being questioned. These ‘mini interviews’ with children will give us insights into how they communicate with the rest of their classmates. Questions will be formulated like they are part of the lessons of the teachers.

Questionnaires will be provided to the teacher/s and the parents. Questions will focus on how the children were diagnosed with autism/ASD, how long have they been studying special education, how they respond to their education, and the progress of the education.

Questions will include something on the family. It will be explained that this is voluntary on the part of the parents and family members.

Literature Review

For purposes of this study, autism can also mean Asperger or Asperger’s Syndrome (AS), high-functioning autism (HFA), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and pervasive developmental disorder (PDD).

Volkmar and Wiesner (2009) provide other terms such as Rett’s disorder, childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD), which is also sometimes referred to as Heller’s syndrome or disintegrative “psychosis”; Asperger’s disorder (also sometimes called autistic psychopathy); and finally, pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) (sometimes termed atypical PDD or atypical autism).

The term PDD technically refers to all these disorders – that is, to the entire group of conditions. The term PDD-NOS is a specific diagnosis included within the PDD category. PDD-NOS refers to a condition in which the child has some trouble suggestive of autism, but these don’t seem to fit the better-defined diagnostic categories – it is essentially a term for conditions that are suggestive of autism but “not quite” autism.

There is another classification that may be associated with the above, or to individuals who manifest anxiety-related symptoms following an extreme traumatic stressor, and this is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

All these terms have been placed under the umbrella term “autism spectrum disorder”. Although the different ASDs may vary in the number and intensity of the behavioral symptoms they share, they have the same broad areas that are impaired, and these are social relationships, social communication, and imaginative thought (Cecile-Kira, 2004).

Asperger’s Syndrome was first reported in 1944 when Asperger wrote on his clinical findings of the children, he studied who were fraught with difficulties such as their inability to build and maintain social relationships or attain reciprocal social interaction, and their inability with peers marked with lack of understanding of social cues and language comprehension problems (Myles, 2003).

Many of the children could talk: some could name things in their environment, others could count or say the alphabet, still, others could recite whole books, word for word, from memory. However, they rarely used their speech to communicate with others. The children had a variety of learning problems in addition to their unusual behaviors. (Shore, Grandin, and Rastelli, 2006)

Asperger published a doctoral thesis using the term autistic in his study of four boys, describing children with Asperger but with developed special interests (Sicile-Kira, 2004).

The case of Fritz V

Asperger’s description of one of the boys named Fritz V. is probably one of the most detailed descriptions of autistic children and autism for that matter. This happened in the early 1930s.

Fritz V. was born in June 1933 and came for observation to the Remedial Department of the University Paediatric Clinic in Vienna. He was referred by his school as he was considered to be ‘uneducable’ on his first day of stay in school. From the earliest age, Fritz never did what he was told, did just what he wanted to, or the opposite of what he was told. He was always restless and fidgety and tended to grab everything within reach.

Fritz was never able to become integrated into a group of playing children. He never got on with other children and, in fact, was not interested in them. He was very aggressive and was thrown out of kindergarten after only a few days. He had attacked other children, walked nonchalantly about in class, and tried to demolish the coat-racks. He had no real love for anybody but occasionally had fits of affection. Fritz did not respect anybody.

Fritz’s family was of good descent. The mother stemmed from the family of one of the greatest Austrian poets. The mother herself was very similar to the boy. The similarity was particularly striking given that she was a woman, since, in general, one would expect a higher degree of intuitive social adaptation in women, more emotion than intellect.

When Fritz talked, he did not enter into the sort of eye contact which would normally be fundamental to the conversation. He darted short ‘peripheral’ looks and glanced at both people and objects only fleetingly. His voice was high and thin and sounded far away. The normal speech melody, the natural flow of speech, was missing. Most of the time, he spoke very slowly, dragging out certain words for an exceptionally long time. He also showed increased modulation so that his speech was often sing-song. He spoke very differently. Occasionally, Fritz would repeat a question or a single word from the question that had apparently made an impression on him. Sometimes, Fritz would sing: ‘I don’t like to say that…’. (Asperger, 2008)

Fritz’s relations with the outside world were extremely limited. This was displayed through his posture, eye gaze, voice and speech. In the ward, he stood out from the rest of the group. He remained an outsider and never took much notice of the world around him. While appropriate reactions to people, things and situations were largely absent, he gave full rein to his own internally generated impulses. There were his stereotypic movements: he would suddenly start to beat rhythmically on his thighs, bang loudly on the table, hit the wall, hit another person, or jump around the room.

Fritz’s emotions were indeed hard to comprehend. It was almost impossible to know what would make him laugh or jump up and down with happiness, and what would make him angry and aggressive. It was impossible to know what feelings were the basis of his stereotypic activities or what it was that could suddenly make him affectionate.

It was clear from the start that Fritz could not be taught in a class. For one thing, any degree of restlessness around him would have irritated him and made concentration impossible. Consider only his negativism and his uninhibited, impulsive behaviour. He was given a personal tutor on the ward, but teaching was not easy. Even mathematics lessons were problematic when, given his special talent in this area, one might have expected an easier time.

Fritz’s writing was atrocious; orthography was difficult. He used to write the whole sentence in one go, without separating words. He was able to spell correctly when forced to be careful. However, he made the silliest mistakes when left to his own devices. Learning to read, in particular, sounding out words, proceeded with moderate difficulties. It was almost impossible to teach him the simple skills needed in everyday life. While observing such a lesson, one could not help feeling that he was not listening at all, only making mischief. It was, therefore, the more surprising, as became apparent occasionally, for example through reports from the mother, that he had managed to learn quite a lot.

It was typical of Fritz, like all the other boys who were diagnosed like him, that he seemed to see a lot using only ‘peripheral vision’, or to take in things ‘from the edge of attention’. But these children were able to analyse and retain what they understood in such glimpses. Their active and passive attention was very disturbed; they had difficulty in retrieving their knowledge, which was revealed often only by chance. But their thoughts can be unusually rich. They were good at logical thinking, and the ability to abstract was particularly good.

Asperger (2008) further says that despite the difficulties they had in teaching Fritz V., they managed to get him to pass successfully a state school examination at the end of the school year. The exceptional examination situation was powerful enough to make him more or less behave himself, and he showed good concentration. Naturally, he astounded the examiners in mathematics. He managed to attend the third form of a primary school as an external pupil, without having lost a school year. (Asperger, 2008)

Definitions

There are various definitions that will be discussed here. According to Myles (2003, p. 9), the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR; APA, 2000) describes Asperger’s Syndrome “as involving two symptom areas:

- qualitative impairment in social interactions (e.g., impairment in nonverbal communication, or failure to form peer relationships);

- restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests or activities (e.g., preoccupation with a restricted pattern of interests, or inflexible adherence to nonfunctional routines or rituals.”

Asperger’s Syndrome is distinguished from more “classic” autism, which involves language and cognitive delays, but not from “high-functioning autism,” in which individuals may have average to above-average intellectual abilities (Myles, 2003).

We assume that people with ASD comprehend what they are talking about since they have a remarkable capacity to employ words that others do not in phrases. Furthermore, individuals frequently use rote memorization to answer questions without fully understanding the response. (Myles, Adreon and Gitlitz, 2006).

According to Myles (2003), the students’ structural aspects of language, for example, the grammar, vocabulary, and articulation, are often intact or even precocious but their conversation skills are impaired.

Sakai (2005) says that children with Asperger Syndrome face a mountain of social challenges, and therefore so do their families. Even with proper diagnosis, it takes time to figure out what the child’s specific issues are, much less how to deal with them.

Priorities for intervention as reported by the National Research Council on Educating Children with Autism include:

- Development of functional, spontaneous communication

- Social instruction in various settings

- Enhancing play skills and peer play abilities (for older individuals, this can be expanded to include a range of leisure-time activities)

- Enhanced academic and cognitive growth including a range of abilities and problem-solving skills

- Positive behavioral interventions for problem behaviors

- Functional academic skills and integration in a mainstream setting as appropriate (Volkmar and Wiesner, 2009).

The overarching goal for the report of the Research Council is to help the individual acquire as many skills as possible to enable him or her to be as productive and self-sufficient as possible as an adult.

Difficulties of children with ASD

Children with autism find it difficult to attend to the instructional situation and are distracted by aspects of a learning situation. In learning, they may have comprehension deficits. But mostly, communication is an area of deficit for children with ASD. They may have well-developed vocabularies and good superficial communication abilities, but they are often not able to communicate effectively in social contexts. They can’t assert themselves with peers, initiate to others, understand figurative language or humor, or grasp the subtle social messages embedded in the communication of others. (Weiss, 2008)

Children and youths with ASD have problems with varied social areas such as nonverbal interactions, reciprocal interactions, inferring others’ mindsets, problem-solving, abstract or inferential thinking, stress, and lack of understanding of self (Myles, 2003). They have difficulty generating multiple solutions to a given situation.

Children with ASD have poor organizational skills, and handwriting is laborious and difficult for them. They also often have sensory integration issues that can make them extra sensitive to light, sounds, tastes, smells, etc. They seem expressive but these are actually comprehension problems. They also “parrot” back information without comprehending the content, and fail to seek clarification. They interpret language literally, and have difficulty in understanding and discussing feelings. (Myles, Adreon and Gitlitz, 2006)

Children with ASD have difficulty in comprehending language related to describing abstract concepts or understanding correctly using figures of speech such as metaphors, idioms, parables and allegories, or grasping the meaning and intent of rhetorical questions.

They are not able to use all their language skills at all times. For example, they may fail to use language when anxious or angry; instead, they engage in disruptive behavior. They need extra support to help them communicate effectively when they are agitated.

Children with ASD experience “meltdowns” associated with a significantly diminished capacity to express feelings or desires. Sometimes the child becomes so agitated that calming becomes the prime objective (Weiss, 2008).

Girls with ASD

The ratio of boys to girls with ASD is four to one. Researchers have long noted that autism is more prevalent in boys than in girls. With Asperger Syndrome, it is closer to 10:1. Although autism and Asperger Syndrome have been researched and reported on for the past 60 years, there is little about the difference between boys and girls with these disorders (Ernsperger and Wendel, 2007).

The ratio of boys to girls with autism and Asperger Syndrome placed in special education is similar. But the prevalence of boys in special education is evidence that the diagnostic and placement focus continues to be on the behavioral characteristics of males, often overlooking the more subtle female characteristics (Ernsperger and Wendel, 2007).

Communicating with children with ASD

According to Schneider (2007), techniques are needed to address many areas in which young people undergo speech therapy, counseling or occupational therapy. Deficit areas include pragmatic language, proxemics, social language, nonverbal messages, problem-solving, group interaction, organizational skills, spatial concepts, motor planning, and sequencing.

Schneider recommended some activities to help children with autism, which have to be done with one or two students and the therapist. Partner activities and scripted scenes could be performed with both the client and the therapist. Co-treatment model pairing speech clinicians and occupational therapists together can be very effective. A lack of spatial awareness is often a deficit in the social understanding piece and also in the way the student’s motor and sensory system is functioning.

Other deficits in autistic children are:

- Failure to use eye-to-eye gaze, facial expression, body posture, and gesture to regulate social interaction;

- Rarely seeking others for comfort or affection;

- Rarely initiating interactive play with others;

- Rarely offering comfort to others or responding to other people’s distress or happiness;

- Rarely greeting others;

- No peer friendships in terms of a mutual sharing of interests, activities, and emotions, despite ample opportunities (Rutter and Schopler, 1988).

The strictly linguistic features, such as the use of grammar, are least affected. But there appears to be a basic deficit in the capacity to use language for social communication.

Other observations are:

- A delay in, or total lack of, the development of spoken language that is not compensated for by the use of gesture or mime as alternative modes of communication (often preceded by a lack of communicative babbling);

- A failure to respond to the communications of others, such as (when young) not responding when called by name;

- A relative failure to initiate or sustain conversational interchange in which there is a to and fro and responsivity to the communications of the other person;

- Stereotyped and repetitive use of language;

- Use of you when I is meant;

- Idiosyncratic use of words; and

- Abnormalities in pitch, stress, rate, rhythm, and intonation of speech (Rutter and Schopler, 1988, p. 19).

It is evident that, because these features concern abnormalities in the communicative process and not just speech, they can be manifest both before the child can talk and after language competence has reached normal levels.

Normal infants use sounds to communicate well before they can talk, and these vocalizations exhibit conversational synchrony and reciprocity. Autistic infants are not like normal ones. It is also different from deaf children who lack speech; they are able to communicate by other means, but autistic children do not. Autistic adults who are able to speak fluently are likely still to show abnormalities in the flow of conversational interchanges, a formality of language, a lack of emotional expression in speech, and a lack of fantasy and imagination (Rutter and Schopler, 1988, p. 19).

Other Communication problems

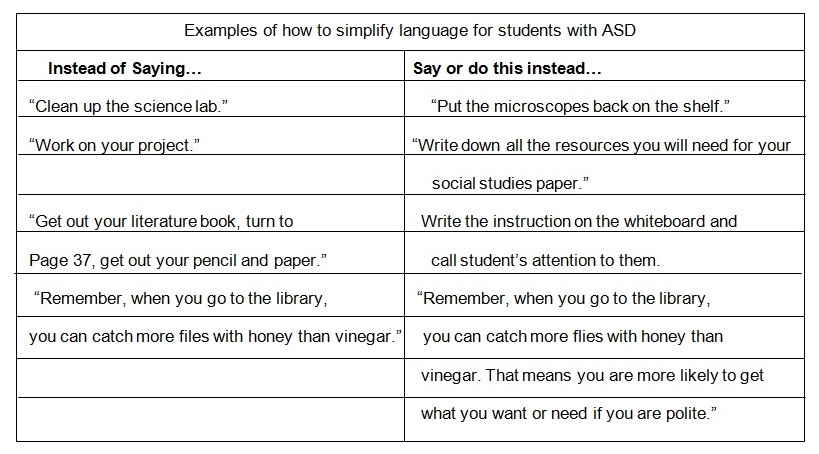

Educators have found it easy to simplify things – or simplify the language. Students with ASD have significant social-communication problems, but according to Myles et al (2006), it is often easy to forget about this aspect of the disability because the students are usually very verbal. Social communication problems refer to the effective use and understanding of communication in a social context, including nonverbal communication such as eye gaze, facial expressions, body language, gestures, and tone of voice.

Many individuals with ASD know words that others do not and have the uncanny ability to use them correctly in sentences, making us believe that they understand what they are talking about. In addition, they often answer questions by relying on rote memory without truly comprehending the answer.

Coping with Children and Youths with ASD

Although children with autism/ASD may have intelligence, they have trouble communicating. Meaning, spontaneous communication doesn’t occur naturally, as it does with neurotypical children. Most young children learn by imitating, watching, and interacting with others. But autistic children don’t develop their abilities on schedule. (Shore, Grandin, and Rastelli, 2006)

A child who has difficulty processing and responding to verbal requests – such as “What’s your name?” – is unable to take part in social and academic settings without some help. Behavioral, developmental, and educational training can be a form of this help.

When clarifying language, specificity is important – “Say what you mean and mean what you say.” General instructions such as “Clean out your desk” may not be specific enough for a student. He might interpret it as sharpening pencils and pushing all the books inside his desk while his teacher had in mind a very different sort of cleaning (Myles, Adreon, and Gitlitz, 2006).

Be specific when providing instructions to ensure that the student knows what to do, how to do it, and when to do it. Be clear and clarify as needed. This includes keeping language concise and simple, saying exactly what you mean, telling the student specifically what to do, breaking down tasks into components, and teaching nonliteral language (i.e., metaphors, idioms). (Myles et al., 2006)

Another helpful strategy is to provide a checklist that breaks larger tasks into more manageable parts that can be checked off when completed. This also serves as a visual support. Such organizational tools help reduce and relieve stress and anxiety.

Given their tendency to be literal and see the world at a very literal, static level, it is no wonder that most students with ASD have difficulties understanding those subtle, unwritten rules that guide and dictate social behavior in different contexts.

Classroom teachers may not think they are actors, but performing is what they do all day long, until it has become second nature. They perform, they direct, they model, and they facilitate all day long. These are the same skills that will be used when implementing some of the antic activities in the classroom. (Schneider, 2007)

The Hidden Curriculum

The hidden curriculum phenomenon has to be explained rightly and at the proper time because it is difficult to grasp by someone with autism. This refers to the set of rules or guidelines that are often not directly taught but are assumed to be known (Myles et al, 2006).

The hidden curriculum contains items that impact social interactions, school performance, and sometimes safety. Idioms, metaphors, slang, or things most people understand through observation within the group or social entity, are some of the hidden curriculum. Body language can be a hidden curriculum.

Each group or social entity has some hidden curriculum. When someone says “get off of my back” with an accompanying body language, the speaker just wants to be left alone, but to a child with autism or AS, that will be a different thing (Myles, Trautman, and Schelvan 2004).

Miles et al (2006, p. 26) recommend this simplification of language technique in communicating with children with ASD:

Furthermore, many students with ASD have difficulties with systematic problem solving. Myles et al (2006) recommend that living out is a strategy that facilitates problem solving and helps students understand their environment and be successful.

This is an example of an exercise from Myles et al (2006, p. 30):

Satellite versus Satellite: “Let’s suppose that Miss Hawthorne is working on a computer next to Miguel, a student with AS/HFA. Miss Hawthorne is trying to find specific information on the Internet on satellites for her science class. She begins by entering the word “satellite”. Her search brings up “satellite offices.” She might then say, “I need to find some information satellites for our science class. I wonder what word I should use to begin my search. I think I’ll type in ‘satellite.’ Oh, let’s see what information came up with the search word – satellite. Ummm … I see some sites on satellite offices and satellite TV, but nothing on satellites in space. I wonder what other word I could use that might get me the kind of information I’m seeking. Maybe I can try ‘space satellites’”.

This classroom exercise can be done by stating it aloud because it helps the students put together what the teacher and others are doing as well as the why and the how. Students with ASD are often distracted by nonessential information and are unsure which details are important to be attentive about. Living out loud helps the student stay on task and understand the salient pieces in a given situation (Myles et al, 2006).

Therapies

A particular treatment or therapy is the Doman-Delacato patterning treatment which involves exercises aimed at forming or correcting neurological organization that has been damaged or never developed. This was created by Doman and Delacato (The Institute for the Achievement of Human Potential [IAHP]) (Myles, Swanson, Holverstott, and Duncan, 2007).

The intervention is based on the belief that the development of a child reflects that of human evolution, for example crawling, creeping, crude walking, and mature walking. Most disabilities are false labels, each representing only different symptoms of brain damage.

Children with disabilities are referred to as brain-injured children. The therapy instituted by IAHP was done on children, regardless of their brain injury, and with the goal that children could attain intellectual, physical and social excellence.

The steps involved determining where injury took place or normal development ceased. A child is then taken through the steps or movements that a typically developing child would go through in that stage. The aim is to train the brain to go through the typical developmental process, believing that this will then lead to a return to normal development. Each level must be mastered before a child can move on to the next level.

Teaching communication skills

The teaching process is very important for children with ASD, and this also depends on the quality of the teaching method and how the teacher is experienced and equipped on teaching communication skills on children with ASD.

Some teaching strategies rely on pictures, physical prompts, and direct modeling rather than verbal explanation. Most children younger than eight years old and those whose verbal IQ is well below average benefit from this strategy. But for older children, and those with good receptive language ability, social skills training strategies can include explanations of why to act in certain ways along with the more concrete strategies that rely on pictures, physical prompts, and direct modeling (Baker, 2003).

Using the concept of time – past, present, and future – to help children remember good conversations can help a lot. Such questions are:

- “How was your week?” (past)

- “What are you playing?” (present),

- “What are you going to do this weekend?” (future)

According to Baker (2003), through this strategy, the children may be able to think of several conversation starters simply by remembering to ask questions about the past, present or future. Other students need a more concrete strategy like memorizing specific sentences to start a conversation.

Incidental Teaching

Another type of teaching is incidental teaching. This is different from discreet trial which is a structured one. Incidental training teaches the child about a social situation as it is occurring, and the goal is to amplify the social environment as it is unfolding so the student can be taught on social cues, rules, other’s feelings and perceptions that are all part of the social situation. The process involves explaining to the child what is happening in a social situation through words or visual aids. The child can be coached and praised.

This can be pointed out during actual situations, for example when a child with autism gets hurt when accidentally bumped by somebody in the hallway. This can be explained to the child why the bump was accidental, so that he will not get angry. The other person’s intentions can be explained, while a hidden social cue is pointed out. The child can respond more appropriately in such a situation.

Incidental lesson is conceptual and relies on abstract information, but it can also be made concrete. For example, to help a child understand when it is her turn in a game, using a card to denote her turn can be used in the process. Visual aids can be used as example to amplify the social environment, like red and green cards to indicate when it is and is not okay to talk in class (Baker, 2003).

Incidental teaching should be an important part of social skills training for children with ASD because it involves teaching children in the real situations where they need the skills. But sometimes, this may not be effective or not enough to teach the child. We have to add other methods like the structured one mentioned above. This is to prepare her/him to deal with the social situation before it arises again.

Social Skill Picture Stories

Another method of teaching children with ASD is the presentation of Social Skill Picture Stories. These are mini-books that depict, step by step, children demonstrating various social skills (Baker, 2003).

Each skill is presented like a cartoon strip, presenting digital pictures of actual children combined with text and cartoon bubbles, telling what the children are saying or thinking as they engage in the social skills. There are explanations in the pictures which present some correct, and some not correct, ways to act. The explanations are very important for the understanding of the child with ASD.

The instructor can present the different skills accompanied by pictures to illustrate each skill step. The instructor can go through each page of a particular skill and then repeat the process to allow the student to grasp the message and relate what is happening in the picture.

The instructor can ask the following questions:

- “What is happening in the picture?

- What is the first step?

- How is he feeling?

- What is he saying?

- What happens next?”

In this way, the students can actively participate in the creation of Social Skill Pictures by posing for pictures and assembling the books on paper. There can be double benefits for this kind of training. The students can role-play the skills during the picture taking and have their attention drawn.

Baker (2003) suggests that in making our own Social Skill Pictures, four areas should be considered:

- ‘what skill to get

- how to break up the skill into simpler steps

- what perceptions, thoughts, or feelings we want to include in the cartoon bubbles to highlight for the student

- how to put the book together.’

There are various ways to set up the Social Skill Pictures. First a skill has to be targeted, along with the accompanying perceptions and verbalizations; then the skill steps and pictures to be presented will have to be mapped out. The students can be used as models for the photographs. Pictures can be taken with a digital camera and then uploaded into a computer.

The next step would be to import the pictures into a Microsoft Power Point Presentation. Bubbles and texts can be handwritten or typed onto colored paper, and pasted on the pictures. The students can participate in the cutting, pasting and assembling of the skills. The sequencing of the skill in the proper order can be made into a game to enhance the understanding of the individual steps.

Using Social Skill Picture Stories reduces reliance on verbal instruction and instructor modeling.

Cognitive Picture Rehearsal

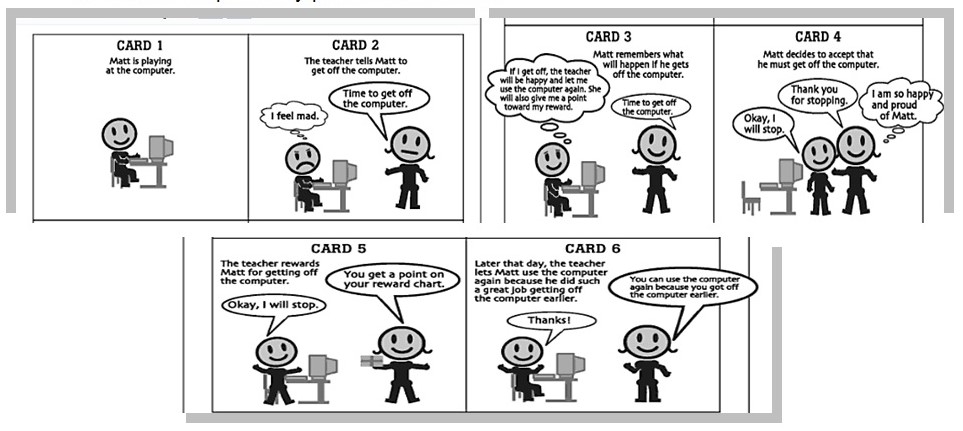

This kind of social skills training utilizes cartoon-like drawings on index cards combined with positive reinforcement principles (Groden & Lavasseur, 1995; Baker, 2003). This is also known as Cognitive Picture Rehearsal that includes drawings or pictures of three components: the antecedents to a problem situation, the targeted desired behavior, and a positive reinforcer.

The process involves displaying the picture on index cards, while on the top of each card is a brief explanation describing the desired sequence of events. The sequence of cards is repeatedly shown to the children so that they themselves can repeat what is happening in each picture. The sequence is reviewed just before the child enters the potentially problematic situation.

Social Stories

Social Stories is a concept developed by Carol Gray and colleagues (Gray et al, 1993; Baker, 2003). These are stories written in the first person and focused on the students’ understanding of what is happening or problematic situations. First, a child’s understanding of a situation is developed; a story then flows leading to the whys and other underlying facts of the situation.

Baker (2003) employs this strategy to students with ASD who believe they are being teased but actually they are not. He cites a 13-year-old who frequently got into fights at lunchtime because he believed that other students were really teasing him. This belief was developed when he sensed that several boys at the other side of the cafeteria were laughing. The boy would give them “the finger”, and soon a fight would start. An investigation or observation was conducted and it was found out that the other boys were laughing but not at the child with ASD. The boys were far away, about 50 feet and were not looking at him. So it was a case of wrong perception. Baker (2003) made this Social Story for the child with ASD:

“When I am in the cafeteria I often see other boys laughing and I think they are laughing at me. Lots of students laugh during lunchtime because they are talking about funny things they did during the day, or funny stories they heard or saw on TV, movies or books they read. Sometimes students laugh at other students to make fun of them. If they are making fun of other students, they usually use the student’s name, or look and point at that student. If the other students are laughing, but they do not look or point at me, then they are probably not laughing at me. Most students do not get mad when others are laughing, as long as they are not laughing at them. If they do laugh at me, I can go tell a teacher rather than give them the finger.”

Structured Learning

Structured Learning refers to the strategies of Goldstein and colleagues in their “Skillstreaming” series (McGinnis & Goldstein, 1997; Baker, 2003), an excellent resource for social skills training that articulates skill steps for numerous skills. This consists of four teaching components:

- Didactic instruction – this involves the instructor – who maybe the teacher, aide, or parent – who will explain the steps of a particular skill, often with the skill steps written on a poster or black board as a visual aid. The key to this approach, or any other approach that relies partially on verbal and written instruction, is to engage the child’s attention. For example, a lot of students are game-show fans, so discussing and reviewing the steps in the form of shows like “Jeopardy,” “Wheel of Fortune,” or “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire?” will usually receive the kind of attention an instructor wants.

- Modeling the skill steps – When the skill steps have been explained, the next step is to model them for the students, and then ask them to carry them out. In this portion of the exercise, the facilitator needs a situation to act as co-actors. There are various situations to act, while students or teachers can serve as co-actors to help model the skills. The attention of the students who are observing should be maintained or focused on the modeling by giving them instructions, like:

“Watch what we do and at the end tell us if we did Step 1, which …, and Step 2, which is …, and Ste 3, which is … Give us a ‘thumbs up’ if we did it right or a ‘thumbs down’ if we did it incorrectly.” The observers therefore are asked to do physical action to keep their attention on the skills. After the modeling skill, the observers are likewise asked whether each step was performed.

- Role-playing the skill – The student is asked to act out the skill steps in the right order. The instructor can participate but not directly, so he can act as a coach to help the students through the skill steps. Again the observers in the role-play are given instructions to see if each step in the role-play is done correctly or not. If children are reluctant to role-play for fear of making a mistake, they can be asked to do something the wrong way and then guess what it was.

- Practicing in and outside the group – The student has to indicate with whom he or she will practice and when. The instructor can tell the students that if they return the assignment sheet and indicate how they practiced the skill, they can receive a bonus prize at the next session (Baker, 2003).

Applied Behavior Analysis

Applied Behavior Analysis is an approach to changing behaviors that uses procedures based on scientifically established principles of learning; it involves a considerable amount of monitoring of the intervention programs, collecting data about the behaviors that we hope to change, and ongoing evaluation of the effectiveness of the intervention procedures (Kearney, 2008).

The first to develop the applied research studies was B. F. Skinner and his students, which is to use a detailed analysis of the behavior of the individual organism. The term applied implies that a technology is being used to achieve a practical effect of more immediate social value. (Bailey and Burch, 2002)

In B.F. Skinner’s (1938, 1953, qtd. in Naoi, 2009), analysis of behavior, human behaviors can be analyzed within the framework of a three-term contingency of operant conditioning, which includes the events that precede behavior (antecedents), the behavior itself, and the stimuli that follow the behavior (consequences).

ABA is practicable to children with ASD. In ABA, the behaviors we target for change are behaviors that can have real-life applications for the children with ASD.

One example of Applied Behavior Analysis is the Discreet Trial Training (DTT). The “discrete trial” refers to a small unit in which an adult, such as the child’s teacher, provides a discriminate stimulus, then followed by the child response and the reinforcement of the response immediately following the child’s response (Naoi, 2009).

The Discreet Trial Training

Most children with ASD have good receptive language ability and would not generally need such structured an approach as discrete trial methodology. But the strategy is extremely helpful for children with limited receptive language ability. The children can be helped by teaching basic words so that they can later respond to verbal instructions and questions. It can also help students attend to a task when they do not respond to verbal instructions to pay attention.

Other important benefits from discreet trial technique include helping students maintain eye contact, and to identify objects, actions, or adjectives. For example, consider a child with autism who does not understand how to respond to instructions like “walk over to the big ball and give it to your teacher.” The child might go through a series of discrete trials to learn the meaning of words like “big,” “ball,” “teacher,” and “walk.”

Baker (2003) further describes discrete trial training. This consists of at least four components: a cue, prompt, behavior, and reinforcement.

In the example above, for the word “big,” the cue might be the words “touch the big ball” (presenting the child with a picture of several small and one big ball). This is followed by the prompt which is to bring or move the child’s finger to the big ball. The behavior then would be to touch the picture of the big ball or the smaller one. And the reinforcement would come as praise and perhaps a material reward whenever she accurately chooses the big ball. This can be repeated using other objects such as toys pencils with one big object mixed in with smaller ones until the child with autism always accurately picks the big item indicating her understanding of the concept of big.

This exercise in teaching communication skills on the child with autism is said to be highly structured and depends on the teacher or trainer cueing the child. Baker (2003) said that it does not typically foster spontaneous social interaction, but it can help in building prerequisite language and attention in preparation for other kinds of training that may facilitate greater social interaction.

Conclusion

Due to their need for structure and predictability, most children on the autism spectrum find it helpful to have a visual concept of what their day, week, or even vacation will be like. In addition to ensuring that the day runs smoothly, the predictability of schedules and other visual supports can help prevent emotional outbursts and meltdowns by relieving anxiety associated with not knowing what is going to happen next.

Recommendations

It has been pointed in the early part of this paper that children with ASD need a lot of understanding in their social re-orientation and integration in order to live a normal and fulfilled life. Most of the types of Autism Spectrum Disorder that we have discussed in this paper point to autism as a disability rather than a mental disorder.

We want to point out that children with ASD can be taught the necessary social skills and classroom lessons, normally and formally as we could, only if the teacher or parents of the children learn and understand the children’s situation.

Understanding and patience in teaching social skills to children with ASD are some of the key points. One way is to first ‘teach’ the teacher the ABCs of ABA; this means the first lessons of Applied Behavior Analysis, and one of these ABCs is the Discreet Trial Training as previously discussed.

We can teach a lot of social skills to children with ASD. It just takes our time and effort to learn first how to do it before we teach them how to learn. Then children with ASD can have a fulfilling life along with ‘normal’ people like us.

Recommendations for Future Research

There have been many programs for the effective teaching and learning methods for children with autism. But these programs have to be continuously improved, remodeled, or reprogrammed because teaching children with autism is a complex and continuous process. The population children with autism increase every now and then, and we have to face the fact that they are part of humanity. We have to properly deal with them and provide them the necessary love, care, nourishment, education, and all the necessary things in life in order for them to grow as normally as they could.

Children with autism are not ‘abnormal’ people that we used to think. They are normal in the sense that they live the way we live in this troubled world. They only look and perceive at things differently. But when they are managed and taught the right way, they can be as effective as normal people. Moreover, they can be more productive than many of us. This has been proven by well-known figures in history who are believed to have autism.

References

Asperger, H. (2008). The case of Fritz V (with annotations from Uta Frith). In J. Rausch, M. E. Johnson, M. F. Casanova (Eds.), Asperger’s disorder. New York: Informa Healthcare USA.

Bailey, J. S. and Burch, M. R. (2002). Research methods in applied behavior analysis. London, UK: Sage Publications, Inc.

Baker, J. E. (Ed.) (2003). Social skills training for children and adolescents with Asperger Syndrome and social-communication problems. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Ernsperger, L., and Wendel, D. (2007). Girls under the umbrella of autism spectrum disorders: practical solutions for addressing everyday challenges. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Gradin, T. (2006). Foreword. In Sicile-Kira, Adolescents on the autism spectrum: a parent’s guide to the cognitive, social, physical, and transition needs of teenagers with autism spectrum disorders. New York: Penguin Group.

Heinrichs, R. (2003). Perfect targets: Asperger syndrome and bullying. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Kearney, A. G. (2008). Understanding applied behavior analysis: An introduction to ABA for parents, teachers, and other professionals. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

MacDuff, G. S., Krantz, P. J., & McClannahan, L. E. (2001). Prompts and prompt-fading strategies for people with autism. In C. Maurice, G. Green, & R. M. Foxx (Eds.), Making a difference: Behavioral intervention for autism (pp. 37-50). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Manasco, K. (2006). Way to A: Empowering children with autism spectrum and other neurological disorders to monitor and replace aggression and tantrum behavior. Shawnee Mission, Ks: Autism Asperger Publishing.

Mesibov, G. B., Browder, D. M., & Kirkland, C. (2002). Using individualized schedules as a component of positive behavioral support for students with developmental disabilities. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4, 73-79.

Moore, S. T. (2002). Asperger Syndrome and the elementary school experience: Practical solutions for academic and social difficulties. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing Company.

Morrison, R. S., Sainato, D. M., Benchaaban, D., & Endo, S. (2005). Increasing play skills of children with autism using activity schedules and correspondence training. Journal of Early Intervention, 25, 58-72.

Mundy, P., Sigman, M., & Kasari, C. (1990). Longitudinal study of joint attention and language development in autistic children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20, 115-128.

Myles, B. S., Swanson, T. C., Holverstott, J., and Duncan, M. M. (2007). Autism spectrum disorder: A handbook for parents and professionals (Volume 2: P-Z). CT: Greenwood.

Myles, B. S., Adreon, D., and Gitlitz, D. (2006). Simple strategies that work: Helpful hits for all educators, of students with Asperger Syndrome, high-functioning autism, and related disabilities. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Myles, B. S., Trautman, M., and Schelvan, R. (2004). The hidden curriculum: practical solutions for understanding unstated rules in social situations. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Myles, B. S. (2003). Chapter 2: Overview of Asperger Syndrome. In J. Baker (Ed.), Social skills training for children and adolescents with Asperger syndrome and social-communication problems (pp. 9–15). Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Myles, B. S., Huggins, A., Rome-Lake, M., Hagiwara, T., Barnhill, G. P., & Griswold, E. E. (2003). Written language profile of children and youth with Asperger Syndrome. Education and Training in Developmental Disabilities, 38(4), 362-370.

Myles, B. S., & Adreon, D. (2001). Asperger Syndrome and adolescence: practical solutions for school success. Shawnee Mission, KS: Autism Asperger Publishing.

Myles, B. S., Cook, K. T., Miller, N. E., Rinner, L., and Robbins, L. A. (2000). Asperger syndrome and sensory issues: practical solutions for making sense of the world. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Myles, B. S. and Southwick, J. (1999). Asperger syndrome and difficult moments: practical solutions for tantrums, rage, and meltdowns. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Naoi, N. (2009). Intervention and treatment methods for children with autism spectrum disorders. In J. L. Matson (Ed.), Applied behavior analysis for children with autism spectrum disorders (pp. 68-71). New York: Springer Science+Business Media, LLC.

National Autism Center. (2007). National Autism Center’s comprehensive treatment models and associated criteria. Boston, MA: Author.

National Research Council. (Ed.). (2001). Educating children with autism. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Rutter, M. and Schopler, E. (1988). Diagnostic Criteria for Autism. In E. Schopler and G. B. Mesibov (Eds.), Diagnosis and assessment in autism. New York: Plenum Press.

Sakai, K. (2005). Finding our way: practical solutions for creating a supportive home and community for the Asperger syndrome family. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Savner, J. L. and Myles, B. S. (2000). Making visual supports work in the home and community: strategies for individuals with autism and Asperger syndrome. Kansas: Autism Asperger.

Schneider, C. B. (2007). Acting antics: a theatrical approach to teaching social understanding to kids and teens with Asperger syndrome. PA, USA: Jessica Kingsley.

Shore, S. M., Grandin, T., and Rastelli, L. G. (2006). Understanding autism for dummies. NJ: John Wiley.

Sicile-Kira, C. (2006). Adolescents on the autism spectrum: a parent’s guide to the cognitive, social, physical, and transition needs of teenagers with autism spectrum disorders. New York: Penguin Group.

Sicile-Kira, C. (2004). Autism spectrum disorder: The complete guide to understanding autism, Asperger’s syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder, and other ASDs. New York, USA: Berkley.

Tsatsanis, K. D., Foley, C., & Donebower, C. (2004). Contemporary outcome research and programming guidelines for Asperger syndrome and high-functioning autism. Topics in Language Disorders, 24, 249-259.

Van Bourgondien, M. E., Reichle, N. C., & Schopler, E. (2003). Effects of a model treatment approach on adults with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 131-140.

Volkmar, F. R. and Wiesner, L. A. (2009). A practical guide to autism: what every parent, family member, and teacher needs to know. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

Weiss, M. J. (2008). Practical Solutions for educating young children with high-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Kansas: Autism Asperger.