Introduction

The influence of bereavement on a person in late adulthood has its own special characteristics. At this age, people mostly already have an established lifestyle, changes in which can lead to unpredictable behavioral responses. This includes emotional response to loss, changes in daily routine, and building and maintaining social bonds. Therefore, this research intends to contribute to a better understanding of the difficulties and possibilities of coping grief by illuminating the experiences of older persons who have lost a spouse.

Literature Review

There is a sufficient amount of literature devoted to the study of human reactions to the loss of a spouse. The most common characteristics of this event are feelings of hopelessness, solitude, and bereavement (Knowles et al., 2019). However, studies by Hanson and Hayslip (2021) and Reitz et al. (2022), demonstrates that the behavior patterns of a person experiencing bereavement in late adulthood differ from other age categories. In addition, there are some gender differences in behavior (Ajdacic-Gross et al., 2019).

Grief and bereavement are the most common emotions in people who have lost their spouses. Features of grief in late adulthood were investigated by O’Connor (2019), Mughal et al. (2022), and Nakagawa and Hülür (2021). In addition, bereavement is a severe emotional state that can significantly affect the functioning of the human body. First, experiencing difficult emotions in adulthood threatens to worsen physical and mental health (Ajdacic-Gross et al., 2019; Knowles et al., 2019).

Second, widowhood can change a person’s social behavior by increasing their need for interaction or, conversely, their need for isolation (Seiler et al., 2019; Santini et al., 2020; Lim-Soh, 2022). However, the existing literature in this area mostly generalizes the behavior of widows without highlighting key patterns in their behavior.

Research Questions

This article aims to respond to the following research questions and the analysis of the questions. What are the behavioral patterns after a loss in late adulthood, and what are the ways of coping with grief? This question includes changes in routines and challenges faced by widowed people. In addition, that implies coping with the emotional impact and making meaning of loss. People choose different behaviors to cope with loss, and these patterns show certain similarities. Moreover, another aspect of this phenomenon is social interaction in search of support, help, and isolation after the death of a spouse.

Methods

Sample

A literature review on bereavement yielded the research used in this synthesis as a subset of references. The following databases were used to search the study’s keywords: CINHAL, Medline, Google Scholar, Psych INFO, ERIC, Sociological Abstracts, and Dissertation Abstracts for all attainable periods. As I could not find enough research using the same qualitative approach and focused on one set of adults, I opted to include studies that used various qualitative methodologies and represented a diverse range of adults. Despite its limitations, I concluded that attempting to synthesize qualitative knowledge on the broad subject of Conjugal Relationships in Late Adulthood was philosophically consistent with the qualitative paradigm and could have significant implications.

Inclusion/ Exclusion Criteria

The main sources for coding were four articles that explored the behavioral and emotional reactions of partners to the loss of a spouse. All sources contain not only the conclusions of researchers about possible patterns of behavior during grief, but also explanations of the widowers themselves of their condition. Therefore, these sources are good material not only for getting acquainted with the general theoretical framework regarding grief and loss, but also for reinforcing it with practical knowledge.

In addition, these 4 sources analyze the reactions of widowed people to the death of their partner from different perspectives. Bennett and Vidal-Hall (2000) focus on the experience of women whose husbands had serious illnesses that led to their death. This material gives an idea of the feelings and emotions of a person living in conditions of predetermined future and limited time.

Since the gender characteristics of the response to the loss of a spouse are a topic of research, materials were selected that can demonstrate them. Collins (2018) focuses her research on the experience of male widowers, characterizing it from different perspectives. A study by DiGiacomo et al. (2015) mainly draws on widowers’ experiences of dealing with government agencies and organizations after the death of their partner.

The source mainly focuses on the features of women’s experience, which often face practical challenges after the death of a husband. Holm et al. (2019) helps to get insights into the nature of social interactions and desire for communication among widowed people. Therefore, these four materials were chosen because they help to better understand people’s behavior during grief from different perspectives.

Results

In general, several main codes can be traced in the behavior of people who have lost their spouse in late adulthood. Each of them chooses his coping strategy for the emotional impact of loss. Feelings of hopelessness, solitude, and bereavement are common responses to losing a partner. However, in most cases, the most common reactions are denial and regret. Some of the women couldn’t accept that their husband was going to die, saying: “It’s all wrong. They’ve told me wrong. They’ve told me a lie” (Bennett & Vidal-Hall, 2000, p. 417).

Many widowed people cannot come to terms with the loss of their spouse or regret the time they did not have time to spend together or “never were able to speak to or say goodbye” (Bennett & Vidal-Hall, 2000, p. 419). For example, one of the women says that she could not go in and speak to him because he never regained consciousness (Bennett & Vidal-Hall, 2000, p. 420). Moreover, many of the widows talk about time limits, especially in cases where their husbands had serious illnesses, and time limits were predicted by doctors.

In cases with severe illness, changes in the spousal relationship are often possible. That happens when one couple becomes disabled, and the other has to be taken care of. However, partners often resent since they have to care for their dying spouse for a long time. One of the women says that her husband’s death “was a relief to me, because life was so hard” (Bennett & Vidal-Hall, 2000, p. 417). In addition, the death of a husband or wife is often accompanied by negative emotions such as anger or shock.

One of the interviewees in Holm et al. (2019) noted that he would like to see him die, not his husband. Such emotional experiences negatively affect the state of physical and mental health. For example, many widowers report that they “have had several heart attacks” after the death of their spouse and that their overall health has worsened (Holm et al., 2019, p. 4). Moreover, one of the men reported that he “had lung cancer and had surgery for that”, and another “struggle with arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 5). In addition to physical health during grief and bereavement, the mental state of a person also deteriorates. One of the widowers notes: “I struggle with my mental health, especially in the evening when I am alone, many thoughts go through my head” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 5). Consequently, after the loss of a spouse in late adulthood, people have to cope not only with the experiences associated with their partner’s death but also with health problems.

Another common code in the behavior of widowed people is the personal growth and transformation. Many lost hope even before the death of their spouse and “put on this wonderful brave face” to hide their emotions (Bennett & Vidal-Hall, 2000, p. 424). Loss of hope is usually the next stage after denying the partner’s imminent death. However, by ending mourning, people often experience a change in mindset and try to find something positive in life. One of the participants notes: “You have to find the light yourself, find moments that light up your everyday life and do something you find positive” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 6).

Furthermore, death is no longer perceived as frightening since “everyone is getting old, slowly but surely dropping off the edge” (Collins, 2017, p. 425). That usually leads to finding new hobbies, activities, or volunteering. For example, it could be golf, swimming, or other leisure activities that help to get distracted. One widower states, “It gives me a feeling that my life is meaningful” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 6). Thus, after the death of a spouse, many widowers need to continue to engage in any activity that can distract them from their grief.

Furthermore, social interaction and support from family and friends are important for coping. In general, when needed for support or expressing emotions, women are more likely to seek out others. Moreover, widows try to stick together and maintain social interaction by finding women with similar experiences, while widowers stay apart. One of the participants states that in church which they attend there is an apparent gender separation since the place where widows are sitting “is a buzz of conversation, and then there’s about half a dozen men sit together separately, all either widowed or on their own” (Collins, 2017, p. 426).

Family support is an important factor that helps to cope with loss more easily. It includes social events like Christmas and birthday parties. In addition, some men say they have tried seeking social interaction with members of the opposite sex with the same experience: “I thought I could just do with meeting one of them” (Collins, 2017, p. 428). That demonstrates the need for communication and bonding to share one’s grief.

In some cases, the theme of gender and social expectations emerged, especially when dealing with governmental agencies. While some note that they received the necessary help and support, others note their absence. Women are often unprepared for practical challenges, noting, “I didn’t know where to start, and I didn’t know where to find things” (DiGiacomo et al., 2015, p. 6). In addition, they often do not receive the necessary help and support. Speaking about her experience, one woman says, “You certainly don’t need banks telling you you’re stupid” (DiGiacomo et al., 2015, p. 5). There are some gender differences in this area, as women are more difficult to cope with the practical challenges of finance. In contrast, men have more difficulty coping with household chores and daily routines.

Moreover, the theme of isolation and loneliness is very common. Widowers often demonstrate dependence and independence on others and are unwilling to feel sympathy or pity. Some “go to the elderly center to eat or buy a meal to take home” or ask their children about it (Holm et al., 2019, p. 5). This behavior can be argued not so much by incompetence but by the desire for social interaction and feeling part of a community or family. Furthermore, neighbors and friends often become the sources of support even with simple actions, like helping in the garden, or bringing plants and food (Collins, 2017, p. 426). At the same time, others “do not want others to take over” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 6). Many of them face misunderstanding, loneliness, and feelings of abandonment.

Moreover, many of them do not want to burden their children, especially if they become disabled and cannot carry out their daily routines on their own. One of the widowers says: “I have to stay at home when I suffer too much” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 6). In such a way man tried to avoid regret from others and did not want to seem weak, so as not to cause feeling of sorry to himself.

However, some widowers choose to isolate themselves due to personal experiences or rejection in society. Many say they “need to go through the grieving process alone” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 5). At the same time, they are wary of others, believing that other people cannot understand their experience or are opposed to them. For example, one of the men noted that people “looked at me as I had done something wrong” (Holm et al., 2019, p. 6). In general, after losing a spouse, many people do not find a way to share their experience because they believe that they will not find understanding and do not realize that their situation is not unique.

Discussion

People in grief and bereavement may exhibit different behaviors. That occurs due to various factors, including age, gender, length of bereavement, and relationships with spouses before their death (Ornell et al., 2020). First of all, the loss of a partner significantly affects a person’s psychological and emotional state, which affects their physical health and social interaction with others. According to Mayer et al. (2019) and Knowles et al. (2019), stress affects key physiological indicators of human health, in connection with which they may develop heart diseases. The words of the interviewees in the four analyzed sources confirm this assumption. Moreover, widowed people often suffer from depression and other serious mental disorders (Monserud, 2019). People who have experienced the death of a spouse are often in a depressed psychological state associated with the loss and change of their usual way of life.

In addition, widowhood significantly affects the social life of people. In the four materials analyzed, people expressed their desire for social interaction differently. While some used communication and socialization as sources of additional support, others preferred to isolate themselves. This observation is supported by studies by Lim-Soh (2022) and Santini et al. (2020). Moreover, differences in the behavior of women and men were analyzed.

Zaheed et al. (2021) and Mayer et al. (2019) note that widowed men are more likely to remarry after the death of their spouse. The data in our study, however, show the opposite, as women make social connections more easily, while widowers prefer to stay apart. Despite that, men are more likely to participate in activities such as volunteering or finding new hobbies (Nakagawa & Hülür, 2021). Thus, the social behavior of the widowed in late adulthood may be conditioned by various factors apart from gender.

Key Themes from the Four Papers

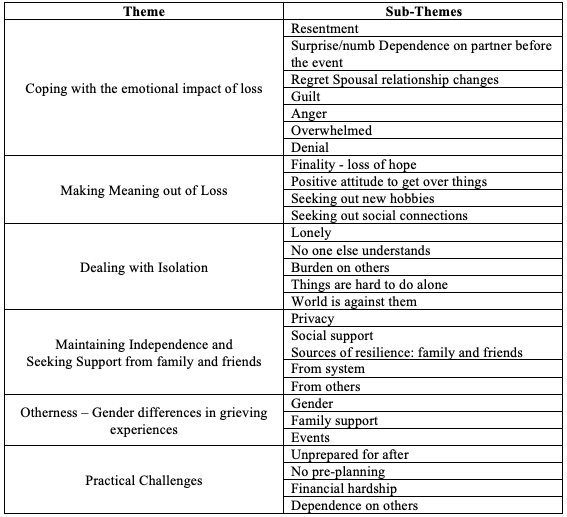

The main themes are coping with emotional impact and making meaning out of loss. A detailed list of themes and sub-themes related to the research of bereavement is presented in Table 1. That includes the underlying emotions people experience while grieving and finding ways to overcome them.

Another critical theme is dealing with isolation and maintaining social interactions after loss. Some people seek communication and support from family and friends, while others isolate themselves from society to experience grief alone. A surviving partner may have difficulty finding their place in the world after their partner dies and struggle with feelings of shame or regret. The support of family and friends and the resources of the wider community are vital in such trying times. It has also become evident that men are more likely to withdraw within and stuff their feelings.

Reflexivity Section

Recognizing the subject’s sensitivity and intricacy is crucial when discussing death and its effect on married couples. How we understand and sympathize with someone who has lost a spouse might be colored by our preconceptions and experiences. Furthermore, our perceptions of how men and women deal with the grief following the death of a spouse may be colored by inherent biases and stereotypes based on gender. Our discussions can be more respectful, inclusive, and empathetic towards diverse experiences if we recognize our own biases and the limitations of the research.

Conclusion

This study contributes to the scant literature on widowers by examining the perspectives of older males as they navigate widowhood within their groups. The findings have important implications for policy and practice because they shed light on older widowers’ challenges. The results first show that some elderly widowers have tiny inner circles, which increases their vulnerability to social isolation. In the future, researchers should consult with older men and women who have lost same-sex partners and do not have children to learn more about their networks after experiencing loss.

References

Ajdacic-Gross, V., Mutsch, M., Rodgers, S., Tesic, A., Müller, M., Seifritz, E., & Preisig, M. (2019). A step beyond the hygiene hypothesis—immune-mediated classes determined in a population-based study. BMC medicine, 17, 1-15. Web.

Bennett, K. M., & Vidal-Hall, S. (2000). Narratives of death: A qualitative study of widowhood in later life. Ageing & Society, 20(4), 413-428. Web.

Brown, R. L. (2022). A Lifespan Approach to Psychological and Physical Health: Attachment and Health in Older Adulthood (Doctoral dissertation, Rice University). Web.

Collins, T. (2018). The personal communities of men experiencing later life widowhood. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(3), e422-e430. Web.

DiGiacomo, M., Lewis, J., Phillips, J., Nolan, M., & Davidson, P. M. (2015). The business of death: A qualitative study of financial concerns of widowed older women. BMC women’s health, 15, 1-10. Web.

Furman, D., Campisi, J., Verdin, E., Carrera-Bastos, P., Targ, S., Franceschi, C., & Slavich, G. M. (2019). Chronic inflammation in the etiology of disease across the life span. Nature medicine, 25(12), 1822-1832. Web.

Hanson, R. O., & Hayslip, B. (2021). Widowhood in later life. In Loss and Trauma (pp. 345-357). Routledge. Web.

Holm, A. L., Severinsson, E., & Berland, A. K. (2019). The meaning of bereavement following spousal loss: a qualitative study of the experiences of older adults. Sage open, 9(4), 1-11. Web.

Knowles, L. M., Ruiz, J. M., & O’Connor, M. F. (2019). A systematic review of the association between bereavement and biomarkers of immune function. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81(5), 415-433. Web.

Lim-Soh, J. W. (2022). Social participation in widowhood: Evidence from a 12-year panel. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 77(5), 972-982. Web.

Mayer, S. E., Prather, A. A., Puterman, E., Lin, J., Arenander, J., Coccia, M., & Epel, E. S. (2019). Cumulative lifetime stress exposure and leukocyte telomere length attrition: The unique role of stressor duration and exposure timing. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 104, 210-218. Web.

Monserud, M. A. (2019). Marital status and trajectories of depressive symptoms among older adults of Mexican descent. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 88(1), 22-45. Web.

Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., Mahon, M. M., & Siddiqui, W. J. (2022). Grief Reaction. StatPearls Publishing. Web.

Nakagawa, T., & Hülür, G. (2021). Life satisfaction during the transition to widowhood among Japanese older adults. Gerontology, 67(3), 338-349. Web.

O’Connor, M. F. (2019). Grief: A brief history of research on how body, mind, and brain adapt. Psychosomatic medicine, 81(8), 731. Web.

Ornell, F., Moura, H. F., Scherer, J. N., Pechansky, F., Kessler, F. H. P., & von Diemen, L. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on substance use: Implications for prevention and treatment. Psychiatry research, 289. Web.

Reitz, A. K., Weidmann, R., Wünsche, J., Bühler, J. L., Burriss, R. P., & Grob, A. (2022). In good times and in bad: A longitudinal analysis of the impact of bereavement on self-esteem and life satisfaction in couples. European Journal of Personality, 36(4), 616-639. Web.

Santini, Z.I., Jose, P.E., Cornwell, E.Y., Koyanagi, A., Nielsen, L., Hinrichsen, C., Meilstrup, C., Madsen, K.R. & Koushede, V. (2020). Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 5(1), e62-e70. Web.

Seiler, A., Von Känel, R., & Slavich, G. M. (2020). The psychobiology of bereavement and health: A conceptual review from the perspective of social signal transduction theory of depression. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 565239. Web.

Zaheed, A. B., Sharifian, N., Morris, E. P., Kraal, A. Z., & Zahodne, L. B. (2021). Associations between life course marital biography and late-life memory decline. Psychology and Aging, 36(5), 557. Web.