Introduction

Nail-biting, also known as onychophagia, is a chronic disorder that is recurrent and persistent and often remains unresolved. It is a problematic oral behavior in which a person places and bites their fingernails. The issue is more prevalent in children and young people, and it is aggravated by underlying anxiety, resulting in a feed-forward impulsive activity that helps the patient feel better.

According to Lesinskiene et al. (2021), nail-biting is an attraction-seeking in kids and teenagers. Onychophagia is associated with poor health, and the condition’s complications range from visible deformation of the nailbed unit to ungual and mouth infections. Chronic damage to the nail unit may also result in gradual nail shortening and degeneration of the distal nailbed.

Faced with the risk of adverse consequences from prolonged nail-biting, this study attempted to reduce the target conduct in an easy-to-implement simple-comparison (AB) design utilizing delayed negative punishment. This single-subject study aims to examine the impacts of the intervention and the success rate of self-monitoring as a catalyst for behavioral change. It is essential to manage nail-biting behavior to avoid developing abnormal-looking fingernails and reduce the damage to the skin around the nails and the tissue that makes them grow.

The study hypothesizes that executing a well-planned behavioral intervention strategy will result in a substantial decline in nail-biting deeds compared to no intervention. Negative reinforcement will be applied to reduce the actions to substantiate the theory, and the treatment results will be compared to a baseline survey. The frequency and severity of nail biting will be measured before and after the intervention to evaluate its effectiveness.

Literature Review

Nail-biting is associated with obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorder, which is frequently overlooked in psychotherapy. It can have a detrimental impact on one’s quality of life and cause bodily and psychological harm. In research by Lesinskiene et al. (2021), Onychophagia is also regarded as a self-mutilative automatic activity, with a prevalence rate of 20 to 30% of the general population.

There are variations in the incidence rate of gender, with research findings ranging from a stronger predisposition in boys to female preponderance and some studies reporting no difference at all (Lesinskiene et al., 2021). In this self-image project, the independent variable is the application of negative punishment, which forms part of the intervention. This involves introducing a consequence, the denial of sausages, contingent on nail-biting behavior.

Randomized controlled research found that habit reversal training (HRT) and object manipulation training (OMT) could help children and adolescents with chronic nail-biting symptoms. In a study by Lee and Lipner (2022), 91 children were randomly allocated to one of three groups, each using various reinforcement approaches based on Applied Behavioral Analysis (ABA) to reduce the target behavior. This research aimed to eradicate or lessen unwanted nail-biting activity, and the results were positive. The researchers discovered that after three months of reinforcement, the average size of the nails in the HRT and OMT groups grew much more than in the control group. The results also showed that HRT was far more successful than OMT.

Furthermore, HRT can be used with stimulus control in the reinforcement treatment of onychophagia. In research by Gur et al. (2018), it emerged that HRT can be enhanced through weekly monitoring with a polish that includes applying a non-removable reminder, such as a topical nail manicure, to maintain patient compliance. For more problematic individuals who bite their nails, daily occlusion of only one nail for two weeks can increase motivation for therapy. This can be achieved by allowing the affected individual to appreciate clinical progress and be inspired to quit chewing the other affected fingernails.

Punishment or aversive therapy, which involves using undesirable methods to prevent patients from nail-biting, has also been used. In the words of Cohen (2022), the methods have proven effective in minimizing obsessive nail-biting behavior. However, patients with an underlying compulsive problem should avoid these approaches. For example, olive oil has been demonstrated to reduce nail-biting habits by making the child’s nails feel soft without distress. Topical treatments with 1% erythromycin, quaternary ammonium-based compounds, and 4% ibuprofen suspended in petroleum are alternatives (Cohen, 2022). Covering the affected fingers and nails with an adhesive bandage for individuals with severe nail dystrophy can help prevent additional damage.

Punishment through nail cleanliness is still essential in avoiding nail biting and associated complications. According to a study by Baghchechi et al. (2021), nail care and regular manicures protect the fingernails and decrease gratification from nail biting. Aversion therapy for onychophagia can further be achieved by adding a bitter-tasting glue to the nails to discourage people from such action since they are likely to avoid the terrible-tasting substance. Its efficacy can be increased by utilizing a milder aversion approach, for instance, wearing a non-removable reminder, such as a rubber band on the wrist, to remind the individual not to bite their nails.

Methodology

The research methodology is based on the AB design model applied in two phases, A and B. Phase A is when a baseline is established, and the treatment is introduced in Phase B. The project involves a single participant from whom the experiment data is recorded directly. The approach entails the participant, a 25-year-old Asian male university student who has the habit of biting nails when stressed, alone, and worrying, collecting data individually. Primary data will be documented using a paper chart to record each occurrence of the behavior in real time. The behavior being documented includes every time the subject engages in nail-biting.

The study began with a three-week baseline period to determine the subject’s initial rate of nail biting. This was followed by a one-week refractory period before the three-week intervention phase. The refractory period aimed to pause the subject and stop continuous recording and note-taking for some time, ensuring higher accuracy during the intervention phase (Symbaluk et al., 2013). Throughout the baseline and refractory periods, the subject’s favorite food was utilized as a reinforcement, and a routine was established during the baseline period of eating the snack at least five times a day. The periods were during breakfast, early morning break, after lunch, during four pm tea, and in the evening after dinner.

During the three-week intervention period, two benchmarks will be introduced to increase the negative punishment for instances of nail-biting. If the subject bites their nails more than five times during one day, they will lose the privilege of eating sausages for that day but can still have the usual portion the following day. If the nail-biting exceeds ten times a day, the subject will not count on sausages for the rest of that day or the following day, which will be a special intervention measure.

This approach will follow a fixed interval (FI) punishment schedule, with the interval being one day, and the principle of negative punishment will be administered during specific periods of the day (Symbaluk et al., 2013). Microsoft Excel will visually represent the information in a scatter plot graph. Subsequently, an independent-sample t-test will be carried out to evaluate the data and ascertain its statistical significance.

Results

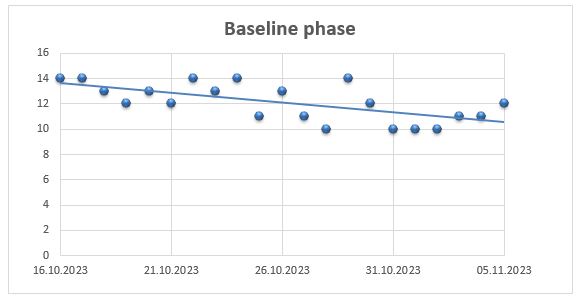

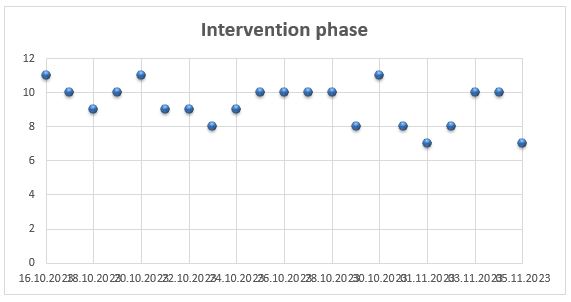

In the baseline phase, the mean instances of behavior (IB) was 12.10, and the standard deviation parameter comprised 1.44. In the intervention phase, the mean IB was 9.29, and the standard deviation was equal to 1.20. Following a comparison of the means using an independent-samples t-test, the time series assessment revealed a statistically critical distinction between the IB during the baseline phase (M = 12.10, SD = 1.44) and the IB indicator documented during the intervention phase (M = 9.29, SD = 1.20), t(20) = 6.47, p <.05).

Figure 3 – Descriptive statistics.

Figure 4 – Independent-samples t-test.

Discussion

The research aimed to review the effectiveness of delayed and immediate negative punishment for frequent nail biting in an individual with onychophagia. The statistical analysis shows a critical difference between the baseline and intervention phases. The findings demonstrate that delayed negative punishment is of particular benefit since individuals can reduce the instances of nail-biting to below the desired value of ten times per day. In contrast, direct punishment by removing sausage privileges was found to be less productive.

Nonetheless, this might be attributed to the stricter criteria for immediate punishment, which may have reduced the individual’s motivation to achieve the goal. The individual was aware that by limiting the behavior to only ten instances in a day, they would face immediate consequences but would not reach the threshold for delayed punishment, allowing them to receive the snack still the following day. Consequently, the individual often consciously decides not to pursue the highest goal level.

Confounding Variables with Points of Friction

There are various confounding variables to consider when determining the incidence of the behavior. These factors conflict with the treatment to explain the study’s findings. They either interfere with the proper association of the research parameters or fraudulently present a perceived connection among the study variables where no genuine connection exists. During the baseline phase, the subject was required to attend school in person full-time, having been previously learning through online sessions.

During the online learning time of the semester, the subject’s behavior was controlled during home classes. When regular in-person classes were back, the subject had less opportunity to engage in the behavior during class time. This had an immediate and noticeable effect on the overall conduct on school days for the rest of the baseline period, as indicated by the trend line in Figure 1. One should highlight that only the information points recorded during the first week of the baseline phase represent the learning period where the subject studied at home, and these days also had the highest occurrences of nail-biting. These differences should have been documented or accounted for in the two datasets.

Another aspect that was not considered was whether or not the subject would participate in the obligatory training exercises as a member of the school soccer team. This characteristic is significant since the person was also unable to engage in the behavior in any other way when at the training site. This variable affected the findings because the subject consistently exhibited a lower rate of nail-biting behavior on Tuesdays and Thursdays, the two mandated training days. It is impossible to tell whether the factor influenced the total instances of the behavior during the duration of the experiment without sufficient data collection on this factor.

The subject’s social connections and gatherings were recognized as a third confounding factor. While meeting friends in person, the subject’s nail-biting happens less frequently, likely because they enjoy their time together. This effect was replicated to a lesser amount on days when the participant would spend social time with relatives, and the behavior was displayed on fewer occasions during these periods.

Since the availability of the subject’s friends to participate in the activity was spontaneous and random, these incidents may have affected the two periods unequally. The variations in these three criteria are not documented or considered in the two data sets. Consequently, they could explain some, if not all, of the differences between the two main stages, namely the baseline and intervention phases, compared to implementing the punishment schedule under consideration.

The primary source of friction in the project is the difficulty of consistently implementing the chosen negative penalty. The pattern enhances the possibility of emotional resistance to the discomfort involved with the reinforcement and difficulty retaining motivation over time, as improvement may be sluggish. The research also needs to identify and treat the underlying triggers for nail-biting in order to achieve long-term success in ending the activity.

Improvement for More Research

While this study presents promising information regarding the productiveness of delayed negative punishment in mitigating the corresponding conduct, some spheres need improvement. Firstly, the whole observation process was initiated, controlled, and documented by the participant, which, in turn, potentially introduces biases that need to be taken into account while reviewing the outcomes of the research (Symbaluk et al., 2013).

The participant is aware of the hypothesis being tested, which creates an additional bias known as demand characteristics. Under these circumstances, the target subject might have tried to satisfy the researcher by following or withholding specific information. Additionally, in this case, the participant performed the function of the researcher. This could have led to a strong motivation to refrain from the desired behavior to succeed in the experiment and confirm the hypothesis offered rather than avoid the implemented punishments.

While this study provides encouraging results regarding the effectiveness of delayed negative punishment in decreasing a specific behavior, some aspects need to be enhanced. To begin with, the study was organized, monitored, and recorded by the participants, leading to several possible biases that must be addressed when looking at the study as a whole (Symbaluk et al., 2013). The subject knows that the hypothesis is to test whether or not the punishment will reduce the behavior.

This bias, known as demand characteristics, makes the participant more likely to try to please the researcher by performing or delaying desired actions. Coupled with the fact that, in this instance, the subject is also the researcher, the subject would feel highly motivated to withhold the desired behavior based on succeeding in the experiment and proving the hypothesis rather than avoiding the implemented punishments.

Another constraint is the self-monitored nature of the study, which could result in what is frequently described as a short-circuiting contingency. This implies that the subject may apply the corresponding punishment only after meeting the pre-established goals. In the study in question, there were instances where the subjects circumvented the punishment during the intervention phase and allowed themselves the snack when the punishment was supposed to be applied. Additionally, there were occasions when they deliberately omitted to count a single instance of the corresponding behavior toward the end of the day, which was aimed at avoiding reaching the planned limit for the subsequent punishment.

In future iterations of this study or similar research, it is essential to introduce the appropriate research-subject separation level to prevent biases from influencing the results. To mitigate individual biases, it is advisable to involve a third party in administering the punishment and recording the corresponding information, thereby preventing situations where the subject can manipulate the contingency.

Furthermore, there is a need to accurately highlight and analyze the impact of confounding variables to strengthen the quality and precision of the importance of delayed negative punishment. Alternatively, more stringent measures can be introduced to eliminate the influence of confounding variables entirely on the study. These measures may include ensuring the subject’s work schedule remains consistent throughout both phases and avoiding significant alterations to the subject’s daily routine and schedule throughout the experiment.

Conclusion

In general, the self-change investigation was successful as it effectively regulated the behavior statistically significantly from the baseline to the intervention phase. Nonetheless, in this case, one key issue arises concerning the outcomes. It is related to whether the reduction in behavior was a direct result of the punishment implemented during the intervention phase or if other factors within the overall experimental conditions contributed to the decrease in the behavior under scrutiny. While a confounding variable influenced the conduct, its impact was primarily due to random chance, making it statistically improbable to favor one stage over the other.

The primary challenge to this study’s credibility stems from the biases displayed by the participant/researcher. The research involved a single individual who possessed complete awareness of the hypothesis and all procedures and the motivation to produce a clinically significant outcome favoring the hypothesis. Given these circumstances, this self-monitored simple-comparison AB subject design is feasible and successful in diminishing occurrences of the targeted behavior, provided that the participant/researcher is adequately driven to validate the hypothesis and decrease the behavior.

References

Baghchechi, M., Pelletier, J. L., & Jacob, S. E. (2021). Art of prevention: The importance of tackling the nail biting habit. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 7(3), 309–313. Web.

Cohen, P. R. (2022). Nail-associated body-focused repetitive behaviors: Habit-tic nail deformity, onychophagia, and onychotillomania. Cureus, 14(3). Web.

Gur, K., Erol, S., & İncir, N. (2018). The effectiveness of a nail‐biting prevention program among primary school students. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 23(3). Web.

Lee, D. K., & Lipner, S. R. (2022). Update on diagnosis and management of onychophagia and onychotillomania. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(6), 3392. Web.

Lesinskiene, S., Pociute, K., Dervinyte-Bongarzoni, A., & Kinciniene, O. (2021). Onychophagia as a clinical symptom: A pilot study of physicians and literature review. Science Progress, 104(4). Web.

Siddiqui, J. A., & Quershi, S. F. (2020). Onychophagia (Nail Biting): An overview. Indian Journal of Mental Health, 7(2), 97. Web.

Symbaluk, D. G., P Lynne Honey, & Powell, R. A. (2013). Introduction to learning and behavior. (4th ed.). Wadsworth.