Background

The article under review investigates the concept of grasp actions. Bub et al. (2018) state that they are directed by the stored manipulation knowledge of an individual and vary depending on the objective to either lift or use an object. It is assumed that lift actions are produced faster and can be accomplished even without prior experience of manipulating the object. Bub et al. (2018) refer to prior studies, which revealed that, regardless of the task’s context, lift actions were generally performed in a quicker manner. In addition, if the objective required a different posture for lift and use grasp actions, production of the latter interfered with the former. It is supposed that the execution of a user action imposes cognitive bias, which affects the subsequent production of lift actions. Bub et al. (2018) theorize that lift actions equally rely on stored manipulation knowledge, and subsequent lift actions see interference from prior experience, while the existing literature does not cover this relation fully. The authors aim to investigate the switch costs, which emerge when use versus lift actions are produced, and all objects remain visible throughout the experiment.

Method

The empirical part of the study involved four major stages. Two different pools of 32 English-speaking students aged 18-26 participated in the first two experiments. The number of subjects in test three was 48, and, for the fourth stage, it was decreased to 31. Students were given cues to perform a simple lift or use action via visuals or imperative sentences in the first two experiments. Next, the third stage introduced the necessity to switch between two blocks of trials in order to observe the presumed use-on-lift interference. In stage four, the intention variable was considered, as students were prompted to perform Action 1 on Object A. In reality, at the last moment, they were told to execute either Action 1 on Object B or Action 2 on Object A. This way, the researchers expected to observe higher interference caused by the influence of an existing intention.

Results

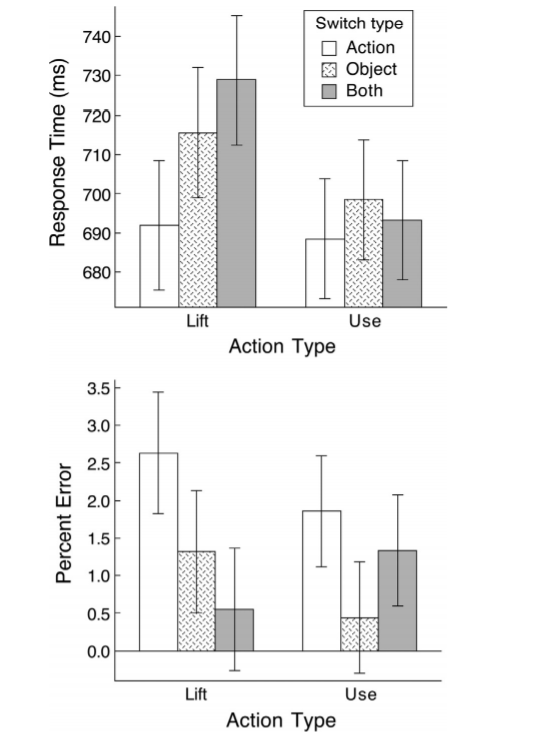

Each of the four experiments yielded promising results in relation to the research area. Throughout the study, the authors did not observe significant differences between the speed of lift and use actions. It was concluded that continuously repeating actions are generally performed quickly, but the variations between two sets of commands were within the error margin. Starting from Experiment Two, switch costs were observed, but they were similar for both use and lift cues. Simultaneously, the third stage revealed that distal goals of lifting could, indeed, be sustained over time, and such cues were followed quickly due to the subject’s predisposition to do so after using an item. In the fourth experiment, Bub et al. (2018) concluded that “the intention to use an object facilitates the prior action of lifting it because the motor sequence – lift then use – is habitually conscripted” (p. 35). Figure 1 shows the findings obtained in the culmination of the study in regards to the perceived response time of different actions.

Discussion

The data collected by the authors of the article under review are highly promising for the discussed research area. The observations imply that use actions correlate with the stored motor knowledge, whereas sudden lift actions can depend solely on the perceived shape and structure of an item. Simultaneously, Bob et al. (2018) discuss that “lift-to-use” sequences are well-defined in the motor system, whereas the opposite cue leads to higher switch costs. However, the primary limitations of the study comprise the participants’ preparedness to perform either task. While some cue sequences were presented in a random order, the subjects were aware of the nature of the experiment. Further studies may comprise a more natural environment, which would reflect the regular processes, which occur for such tasks. This way, additional insight into the roles of knowledge and structural motor representations will be provided.

Reference

Bub, D. N., Masson, M. E. J., & van Mook, H. (2018). Switching between lift and use grasp actions. Cognition, 174, 28–36. Web.