Abstract

This laboratory report will exhaustively describe an experiment on how it is possible to influence people’s attention. The study’s aim is to determine how and whether valid and invalid cues can impact attention results and response time. Thus, this research’s hypothesis states that valid cues improve people’s attention and result in reduced response time when compared to invalid ones. The study’s methodology implies 205 voluntarily selected participants, including 34 men and 171 women, who are asked to complete a test that measures their attention and response time. Ninety-six trials include either valid or invalid cues, and a computer estimates how long it takes for the participants to respond to the following “GO” signals.

The obtained results are then analyzed to produce descriptive statistics, including mean values and standard deviation, and this information forms the input data for the t-test. This statistical test demonstrates that valid cues result in 65.32872-76.43714 milliseconds shorter response time regarding a 95% confidence interval in comparison with invalid signals. Appropriate calculations show that the results are significant and scientific, meaning that there is a low probability that a chance has influenced or contributed to the findings. This information indicates that the experiment has proved and justified the research hypothesis. In addition to that, the study implies some limitations that can influence the findings. It refers to the failure to consider the participants’ age and identify the effect of various valid and invalid cues correlations. Consequently, the study mentions future scientific directions that researchers should follow to determine whether these results are significant and unbiased.

Introduction

Attention is a significant topic of the research field, and many scientists conduct studies to analyze and test this phenomenon. Posner et al. (1980) created one of the most famous research pieces on the topic. According to the researchers, “detection latencies are reduced when subjects receive a cue that indicates where in the visual field the signal will occur” (Posner et al., 1980, p. 160). That is why it is reasonable to consider what other scientific works also address this issue and offer noteworthy findings. Jackson et al. (2010) admit that an attention rate was higher if “the direction of the proprioceptive stimulus was compatible with the location of the visual target” (p. 31). Simultaneously, Bestelmeyer and Carey (2004) mention that invalid cueing leads to slowed reaction times. This information denotes that valid cues allow people to respond faster.

At the same time, it is reasonable to consider that cue validity implies additional consequences. As Jaeger et al. (2020) argue, this phenomenon leads to more accurate results of attention tests. Individuals know in advance where a figure or another object appears, which allows them to minimize the number of mistakes. It is also worth mentioning that cue validity is not only associated with blind following the cues. A study by Jollie et al. (2016) shows that the indication of the most or least likely target location also facilitates target processing. It means that valid cueing makes people accumulate their attention capabilities.

Furthermore, one should explain why the phenomenon under consideration implies this effect. Imhoff et al. (2019) stipulate that valid cueing only leads to positive outcomes if an experiment has more valid than invalid cues. The researchers suppose that an approximately equal number of valid and invalid signals will not result in a shorter response time (Imhoff et al., 2019). However, multiple scientific works oppose this idea, and the studies by Malevich et al. (2018) and Johnson et al. (2020) are among them. On the one hand, Malevich et al. (2018) state that reduced reaction time is “the result of a cue-target perceptual merging due to re-entrant visual processing” (p. 106). It is so because there is a robust connection between a cue and a target, which allows people to spend less time reacting. On the other hand, Johnson et al. (2020) demonstrate that reaction time is lower since valid cues are preliminary information that facilitates decision-making. Consequently, there are various explanations to understand why valid cueing results in shorter response times.

The literature review above is of significance for the given research paper. It is so because multiple studies demonstrate that valid cues provide individuals with an ability to achieve shorter reaction times. It denotes that people’s attention is mobilized when there is a signal of an upcoming event. Even though one study stipulates that positive results of valid cueing are biased, all the other research pieces prove that this phenomenon indeed facilitates people’s attention. This information provides a sufficient basis to keep investigating this issue in practice.

At this point, it is reasonable to present this study’s hypothesis that reflects the research aim and is derived from the literature review. Thus, the claim under analysis is that valid cues improve people’s attention and result in reduced response time. Consequently, the given report will explain whether it is reasonable to expect that individuals will respond faster if they are given a signal to prepare for action.

Method & Results

The experiment under consideration implies a transparent methodology that can be easily replicated. A sample size consists of 205 participants, including 34 male and 171 female individuals. The data on their age are not present because they are irrelevant to test the credibility of the hypothesis under analysis. The sample size was comprised of volunteers, which was necessary to ensure that the participants will be interested in the experiment task. Before the experiment, the participants are carefully instructed to achieve the correctness of the obtained information.

As for the experiment, it makes the participants cope with an easy assignment. A screen shows a fixation cross in the center and two boxes – one to the left and the other to the right from it. In each trial, a “GO” word appears in any of the boxes. The participant’s task is to press an “s” button if it appears in the left box and a “k” button if it emerges in the right one. Thus, the participants’ responsibility is to be sufficiently attentive and press an appropriate button as immediately as possible.

The experiment is peculiar because it implies valid and invalid cues that are represented by an “X” that also appears in the boxes before a “GO” word. A signal is valid if a “GO” signal appears in the box from which an “X” has disappeared. Simultaneously, an invalid cue relates to the situation when consecutive “X” and “GO” signals emerge in different boxes. Thus, the participants have two strategies to follow, and their response time is the variable of interest. Consequently, the system determines how long it takes for people to respond to valid and invalid cues.

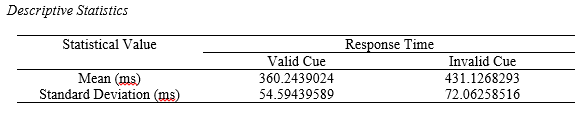

The results of the given experiment are presented in Table 1. The mean response time for valid cues is 360.2439024 milliseconds and 431.1268293 milliseconds for invalid cues. A lower standard deviation for valid signals of 54.59439589 milliseconds compared to 72.06258516 milliseconds for invalid ones demonstrates that many participants show results that are close to the average. The t-test is necessary to determine whether these findings are significant. A t value of 25.162 shows that the two conditions under consideration imply substantially different results. Valid cues lead to 65.32872-76.43714 milliseconds shorter response time regarding a 95% confidence interval. A degree of freedom of 204 and a p-value of less than.001 prove the hypothesis and highlight the evident impact of valid cues on people’s response time. It is so because these low statistical values denote that an accident has no effect on the findings.

Table 1.

Discussion

The experiment findings prove that there is a robust connection between valid cues and shorter response times. A diverse sample size of 205 individuals generated data that were then transformed into descriptive statistics. The obtained values were useful to conduct the t-test that was necessary to compare two means and determine whether there was a significant difference between the two. According to this statistical test, there are fundamental discrepancies between how valid and invalid signals influence response time. It is possible to state with a high degree of certainty that valid cues mobilize people’s attention and lead to their shorter response time. Consequently, statistical and scientific evidence proves the hypothesis stating that valid signals improve people’s attention and result in reduced response time.

In conclusion, it is worth mentioning that these findings support most ideas that have been covered in the literature review. The experiment results demonstrate that valid cues lead to shorter response times, while invalid cueing contributes to individuals’ more mediocre measures. It is so because valid signals provide people with preliminary information on where and when an upcoming event is going to occur. As a result, people mobilize their attention and are ready to make instant decisions. In turn, invalid cues lead to the completely opposite results because they mislead people’s attention, which results in longer response times. The experiment has supported the evidence of studies by Posner et al. (1980), Jackson et al. (2010), Bestelmeyer and Carey (2004), Malevich et al. (2018), and Johnson et al. (2020). Thus, the findings are in conformity with the literature on the topic.

Simultaneously, it is reasonable to state that the experiment implies a few limitations. Firstly, participants’ age was not recorded, but this phenomenon can significantly influence attention indicators. Secondly, it is not rational to ignore the claim by Imhoff et al. (2019), who states that response times depend on whether there are more valid or invalid cues. his information means that future research is necessary to determine how valid and invalid signals influence participants’ response time if they represent various age groups. It will be suitable to identify numerous samples for this research. Furthermore, it is useful to test whether various correlations of valid and invalid cues can result in different findings.

References

Bestelmeyer, P. E. G., & Carey, D. P. (2004). Processing biases towards the preferred hand: Valid and invalid cueing of left- versus right-hand movements. Neuropsychologia, 42(9), 1162-1167. Web.

Imhoff, R., Lange, J., & Garmar, M. (2019). Identification and location tasks rely on different mental processes: A diffusion model account of validity effects in spatial cueing paradigms with emotional stimuli. Cognition and Emotion, 33(2), 231-244. Web.

Jackson, C. P. T., Miall, R. C., & Balslev, D. (2010). Spatially valid proprioceptive cues improve the detection of a visual stimulus. Experimental Brain Research, 205, 31-40. Web.

Jaeger, A., Queiroz, M. C., Selmeczy, D., & Dobbins, I. G. (2020). Source retrieval under cueing: Dissociated effects on accuracy versus confidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 46(8), 1477–1493. Web.

Johnson, M. L., Palmer, J., Moore, C. M., & Boynton, G. M. (2020). Endogenous cueing effects for detection can be accounted for by a decision model of selective attention. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 27, 315-321. Web.

Jollie, A., Ivanoff, J., Webb, N. E., & Jamieson, A. S. (2016). Expect the unexpected: A paradoxical effect of cue validity on the orienting of attention. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78, 2124-2134. Web.

Malevich, T., Ardasheva, L., Krüger, H. M., & MacInnes, W. J. (2018). Temporal ambiguity of onsets in a cueing task prevents facilitation but not inhibition of return. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 80, 106-117. Web.

Posner, M. I., Snyder, C. R., & Davidson, B. J. (1980). Attention and the detection of signals. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 109(2), 160–174. Web.