Introduction

Susan and Jack’s son, Edward has been growing stronger and bigger since birth. By the time Edward reached his third birthday, he is over twice as tall as he was at birth and nearly three times as heavy.

A child’s body changes and grows in a predictable pattern. Physical growth occurs in three distinct phases from birth to adolescence. Following the tremendous growth during infancy and toddlerhood, growth in childhood slows down to a steady rate of about 2 to 3 inches a year in height and about 5 to 6 pounds in weight. The third phase is the dramatic “growth spurt” that occurs during adolescence.

During the preschool years, both boys and girls slim down as the trunks of their bodies lengthen. Although their heads are still somewhat large for their bodies, by the end of the preschool years, most children have lost their top-heavy look.

Brain Development

The brain and head grow more rapidly than other parts of the body in early childhood, although at a slower rate than that during infancy. By the time children reach three years of age, the brain is about three-fourths its adult size. By the age of five years, the brain has reached nine-tenths its adult size.

Throughout infancy, childhood, and even into adolescence, myelinization of the nerve fibers occurs. In this process, the axon projection fibers are covered and insulated with a layer of fat cells. Myelinization results in increased speed of neuronal transmission throughout the nervous system. There may be spurts of myelinization in different areas of the brain, a factor which may account for some of the remarkable increases in certain skills such as language, seen in early childhood.

Motor Development

Due to a relative lack of motor coordination in early childhood, children may trip, fall from the jungle gym, or have difficulty manipulating writing and art tools. As children move their legs with more confidence and carry themselves more purposefully, their physical movement becomes more automatic.

At the age of three years, the fine motor skills of children are not well developed yet. However, by the age of four years, fine motor coordination improves substantially and becomes more precise.

Health issues are common in early childhood. Let’s learn about health issues in early childhood.

Health Issues in Early Childhood

Edward has a difficult time with ear infections and he is seen by his pediatrician on a regular basis for the treatment of otitis media effusion (OME) or fluid in his ears. Finally, by the time he is four years old, tiny tubes are placed in his eardrums to keep his ears clear. Susan and Jack are informed that otitis media could have some long-term impact on Edward’s development and that they need to monitor this closely.

A potentially serious condition affecting many young children is OME, or commonly referred to as an ear infection. In a 1997 study reported in Pediatrics, children with severe and chronic ear infections showed a marked decline in motor development. In addition, some research has found a link between children with chronic OME and later problems with language acquisition, balance, and hearing loss.

Nutritional problems occurring in early childhood, most commonly among poor children, are:

- Iron-deficiency anemia, resulting in chronic fatigue

- Growth retardation, as a result of not eating adequate amounts of quality meats and dark-green vegetables

It is estimated that 11 million children are undernourished in the U.S., most of them from low-income families.

In recent history, vaccines have nearly eradicated disabling bacterial meningitis and have become available to prevent measles, rubella, mumps, diphtheria, polio, and chicken pox. Some additional health concerns are that children who are exposed to parental smoking are at an increased risk of developing medical problems such as pneumonia, bronchitis, middle-ear infections, burns, and asthma.

A child’s cognitive development begins when the child is born. Research suggests that there is a strong relationship between the cognitive development of a child during early childhood and the level of success later in life. Let’s learn all about cognitive development in early childhood.

Susan and Jack are very excited about the school they have chosen for Edward. They are fascinated when they learn about what goes on in preschool and how their son will be challenged.

Early-Childhood Education

The idea of giving children a good foundation and an early start along the path of life is ancient. However, the idea found strong advocacy in the U.S. as early as 1823, when New York Governor De Witt Clinton encouraged the establishment of infant schools so that poor mothers could go to work while their children were being given moral and character training. The idea caught on in Philadelphia and especially Boston, where 40 percent of all three-year olds were enrolled in school. By the close of the century, however, this idea was no longer in favor with the emerging strength of the public school system, which wanted nothing to do with infants and toddlers.

Cognitive Developmental Needs of Children Addressed in Preschool Programs

The dynamic systems theory of motor development states that a child’s maturation is tied to the development of gross and fine motor skills. In other words, a child’s physical movements are thoroughly integrated with the environment, therefore, producing specific behavioral consequences. As a result, the child’s physical and cognitive development becomes an interactive process impacting behavioral patterns. This theory is consistent with the recommendations of National Association for the Education of Young Children’s for developmentally appropriate activities for preschool and school-aged children.

The Head Start program was developed by the Federal government to provide the children of lower socio-economic status with preschool readiness programming. The idea was that these children could directly join regular school programs in elementary school without attending preschool. The interesting side effect of this program was its influence on middle-class parents, who felt that their children should also have some sort of ”head start” in the early years of their education. This awareness, coupled with the increasing number of mothers entering the workforce, made the preschool or day-care center popular. Additionally, parents supported the addition of kindergartens to their public schools.

In the 1980s and 1990s, published reports by researchers, which indicate that early education greatly stimulates later learning success, increased the popularity and demand for quality day care. The reaction to this was some loud dissent that early school is detrimental because it begins a pattern of stress, which can interfere with a child’s normal growth and development. However, conclusive research on the topic revealed that there is no detrimental effect of early education and that indeed it improves a child’s overall developmental progress. Therefore, early education has become a categorical imperative now.

Let’s turn our attention to the different models of childhood education programs that are in vogue in the U.S. now.

Literacy and Early-Childhood Education

Literacy begins in infancy. Reading and writing skills for preschool children should build on existing understanding of oral and written language. Too many preschool children are being subjected to rigid, formal prereading programs with expectations and experiences that are too advanced for their cognitive levels of development. This results in extreme stress on children. Therefore, instruction should be built on what children already know about oral language, reading, and writing.

Variations in Early-Childhood Education

There are at least three different types of early education models used within preschools in the U.S. They are:

- Montessori approach, which is a philosophy of education in which children are given considerable freedom in choosing activities. Children are allowed to move from one activity to another as they desire, and the model does not emphasize verbal interaction between teacher, child, and peers.

- Child-centered kindergarten, which includes developmentally appropriate practices, where experimenting, exploring, discovering, trying out, restructuring, speaking, and listening are encouraged. This model requires teachers to know that children develop at varying rates. Therefore, educators and psychologists promote programs in which the child’s specific developmental level is taken into consideration. These programs emphasize hands-on activities rather than paper-and-pencil activities or otherlarge-group strategies. This model involves whole child development taking into account the physical, cognitive, and social development on one hand and the child’s needs, interests, and learning styles on the other.

- Nonsexist early-childhood education, which aims at meeting the following goals:

- Free children from constraining stereotypes of gender roles.

- Promote equality for both sexes by facilitating each child’s participation in activities.

- Help children develop skills that will enable them to challenge sexist stereotypes and behavior.

Does Preschool Matter?

The issue is not whether preschool is important, but whether home schooling can closely duplicate what competent preschool program can offer. Psychologist David Elkind believes that early-childhood education should become a part of public education, but on its own terms. He believes that early childhood should have its own curriculum, its own methods of evaluation and classroom management, and its own teacher-training programs.

Early childhood is a time of tremendous social and emotional growth for children. This is the time for the child to tentatively venture into the world and form his/her first social relationships that can exert a strong influence on other relationships in later life. Let’s learn more about socioemotional development in early childhood

Jack and Susan make every effort to expose Edward to different types of people, with the hope that by the time he joins kindergarten, he would be well socialized.

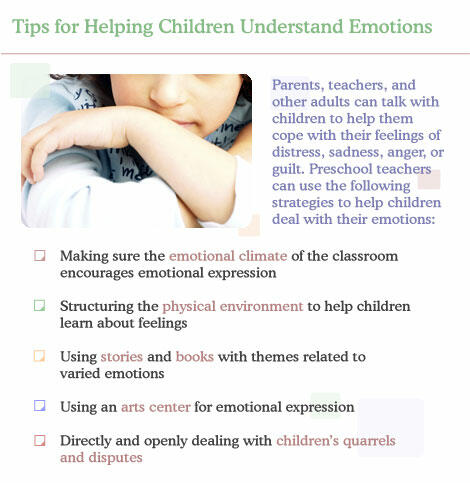

Emotional Self

Most theorists and researchers agree that the emotional health of children aged two years old through six years old is dependent upon their relationship with the primary and secondary caregivers. More recently, however, developmentalists are considering the impact of child temperament on parenting styles and its ultimate effect on the emotional stability of the child. This brings us to the nature-nurture question: Is a young child’s emotional makeup a result of parenting style or of the child’s genotype?

Brazelton of Boston’s Children’s Hospital Child Development Center stresses the importance of parental adjustment to the child’s temperament. If a child has a sensitive or finicky temperament, a parent’s reaction of anger or frustration may inhibit the child’s emotional control especially when the child reaches school age.

According to Sandra Scarr’s evocative-genotype-environment concept, babies and small children can evoke positive and negative responses from the caregiver. As per the studies in the area of mother-child relationships, positive socioemotional development of children is positively related to the patterns of emotional language between mothers and children.

For the child, the prime sources of learning about emotions are the verbalizations of the parents. This includes their mode of reaction to peers and emotional expression in general. The emotional lives of caregivers act as models for the young child’s emotional reactions.

The studies of preschoolers’ interactions with siblings, peers, adults, and strangers support the theory that parental influence is essential to the preschoolers’ emotional development. These studies reveal that children’s adaptive regulation skills develop as a result of the positive affective sharing that occurs between caregivers and children during their day-to-day social exchanges.

Additionally, studies confirm that socioemotional competencies are associated with positive expressiveness within the family in terms of prosocial behavior.

Erikson’s Psychosocial Stage of Self-Initiative vs. Guilt

Erikson’s psychosocial stage of initiative versus guilt applies to the early-childhood stage. At this stage, parents’ reactions to their children’s actions greatly influence the development of the self. Erikson believed that conscience is the governor of initiative; it is an inner-voice of self-guidance, which easily returns guilt for actions deemed wrong. For Erikson, this is the cornerstone of morality.

Here are some facts about Erikson’s Psychosocial Stage of Self-Initiative vs. Guilt:

- This psychosocial stage characterizes early childhood.

- It occurs because children use perceptual, motor, cognitive, and language skills to make things happen.

- The governor of initiative for children at this age is conscience, which generates in children a feeling of fear of being found out, while the children hear an inner voice of self-observation, self-guidance, and self-punishment.

- At this stage of development, preschoolers become more adept at talking about their own and others’ emotions.

- Two- to three-year-old children considerably increase the number of terms they use to describe emotions.

- Four- to five-year-old children begin to understand that the same event can elicit different feelings in different people.

Research suggests that parents play a significant role in a child’s overall growth. Parenting style can enhance or inhibit a child’s growth into a mature, responsible adult. Let’s learn more about parenting.

Adaptation of Parenting to Developmental Changes in Child

The key considerations about parenting include:

- Parents need to adapt their behavior to their child, based on the child’s developmental maturity.

- Parents cannot treat a two-year-old child the same way as they would a five-year-old child because children in both these age groups have separate needs and abilities.

Parental influence is pre-eminent to a child’s emotional maturity. Therefore, parenting styles would interest psychologists attempting to determine what

child-rearing practices will provide the optimum environment for the healthy emotional growth of the child. Diana Baumrind’s parenting styles place most parents in one of three categories. However, on close examination, it usually becomes apparent that very few parents fit any single definition. Parents apply all three styles of parenting depending on the situation and their own maturity level. Indeed, it is not uncommon to find two separate types of parenting styles emanating from each parent.

Diana Baumrind’s Three Types of Parenting Styles

Three types of parenting styles include:

- Authoritarian style is a restrictive, punitive style, where parents demand that children follow directions and respect work and effort. Parents place firm limits and controls on the children. This allows minimal to no verbal exchange between a parent and a child when the parent gives a direction.

- Authoritative style parents encourage children to be independent but place limits and controls. This style encourages extensive verbal exchange between the children and their parents.

- Permissive style parents are highly involved with their children, but place few demands or controls on them.

Now let’s turn our attention to another important aspect of a child’s life, sibling relationships. First, let’s learn a few interesting facts about birth order among siblings.

Interesting Facts about Birth Order

- The oldest child is the only one who does not have to share parental love and affection with other siblings.

- An infant requires more attention than the older child; this means that the firstborn sibling receives lesser attention after the newborn arrives than before.

- Parents have higher expectations for the first-born children and put more responsibility and pressure on them for achievement.

Statements about birth order might be valid when two-parent families have one wage earner, which was the ”norm” in America at one time. However, current families are referred to as omnigamous as coined by Lionel Tiger in an essay, which attempts to define the modern family. Given just one divorce each, a man and a woman could conceivably build a family structure with eight grandparents, more than four step children, step brothers, and step sisters. With such diversity, it is no longer possible to refer to either the family in traditional terms or the parenting styles as a static category of behavior serving as a template for parental strategies.

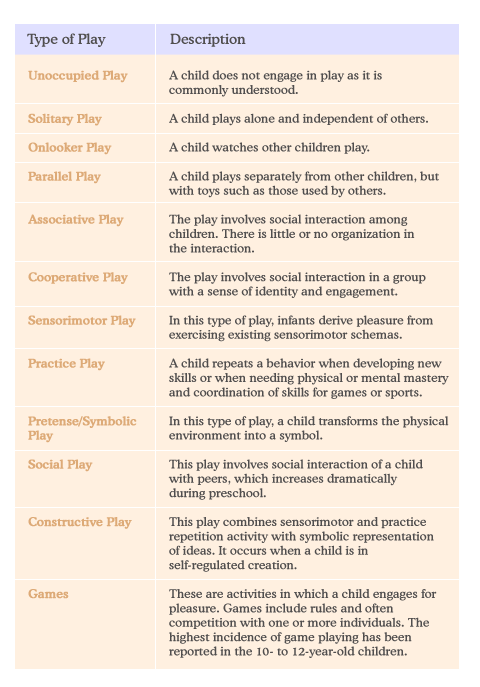

Play is a leading source of socioemotional development in preschool years. Let’s learn about different types of play.

Early-Childhood Play

Young children learn about themselves and the world through play. They learn symbols, colors, sizes, textures, emotions, sensations, sounds, and language by playing. Children also learn important social interaction with peers by playing. Play is also a way to practice what they learned. As the child engages in make-believe play, acting out the roles of sisters or brothers or parents or other social roles that they are familiar with such as a doctor or a vendor, the child practices and refines acceptable patterns of adult behavior.

Parten’s Categories of Play

While there are many theories of play, Mildred B. Parten’s stage classification of children’s play is considered as one of the best descriptions of how play develops in children and has become a required reading for potential elementary school teachers. In 1932, Parten defined a number of types of early childhood play:

Now let’s turn our attention to another significant aspect of young children’s development, moral development.

Edward’s parents are very concerned because Edward has taken two dollars out of his mother’s purse without informing his parents. Doesn’t he understand that stealing is wrong? Jack and Susan wonder what consequence stealing would have on Edward’s moral development.

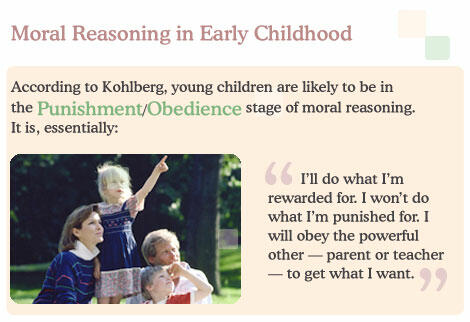

Moral Development

Moral development concerns rules and contentions about what people should do in their interactions with other people.

An approach, best exemplified by Lawrence Kohlberg, focuses on the different types of reasoning children use to justify their moral decisions. There is little understanding of motives or intentions; in other words, young children judge the act by what happens as a result and not by a person’s intentions.

Ask any two- or three-year-old child what is worse, Sally intentionally breaking a glass or Suzie accidentally breaking 10 glasses. What you’ll undoubtedly hear is that what Suzie did was much worse because she broke 10 glasses. Again, this illustrates that young children do not understand a person’s motives or intentions

This week, you explored the early-childhood stage of development.

You looked at physical issues such as body growth, brain development, motor development, and health issues such as ear infections and inadequate nutrition.

You discussed cognitive issues including cognitive processing skills of attention and memory, early-childhood education, and preschool programming.

Socioemotional issues related to this developmental period of the lifespan were examined. You discussed in detail the influences on the emotional growth of children such as parenting styles, birth order, and sibling relationships. Other issues such as early-childhood play and moral development in children were discussed.