Introduction

Since its introduction by Festinger, the concept of cognitive dissonance has received widespread recognition in multiple fields that involve human behavior patterns. Eventually, the concept was applied to organizational studies, where it offered numerous benefits associated with improvements in employee motivation, engagement, and behavioral patterns.

Leadership has become an especially promising area for inquiries on cognitive dissonance, both because leaders are highly vulnerable to attaining cognitive dissonance and due to its numerous possible effects on their professional performance (Verma & Anand, 2014).

Nevertheless, despite its obvious relevance to the area of cognitive dissonance in leaders, the issue remains under-researched, and many of the existing studies on the matter deviate significantly from the academic concepts and lack precision of definitions, which renders the obtained findings unreliable or obsolete (Hinojosa, Gardner, Walker, Cogliser, & Gullifor, 2017). While a recent increase in interest to the topic can be observed among researchers, the available information is insufficient to arrive at a meaningful conclusion.

To further complicate matters, some scholars suggest the possibility of positive effects of cognitive dissonance, which can be considered relevant once their implications are confirmed by valid data (Adams, 2016). To sum up, an exploratory inquiry in the area of cognitive dissonance can produce valuable findings and is necessary to direct further researches and outline potential areas of interest.

Rationale

Modern organizational culture relies heavily on innovation. Properly implemented innovative approaches are known for their ability to facilitate and sustain competitive advantage, increase and maintain the necessary level of productivity, and improve efficiency on both organizational and individual levels. However, the process of innovation is strongly associated with resistance to change and an overall increase in individual stress among employees (Verma & Anand, 2014).

Leaders are not exempt from this effect as the change undergone by the organization can conflict with their personal and professional values. Since they are expected to inspire their team to engage in activities that do not necessarily coincide with their beliefs and values, the possibility of developing cognitive dissonance in the process is further increased. According to numerous sources, such scenario can result in the disruption of organizational performance, decline in individual involvement, loss of motivation within the leader’s team, and increased employee turnover (Wicklund & Brehm, 2013). Interestingly, some evidence exists that these effects can be minimized through conscious effort on the part of the impacted party.

For instance, some experts point out that the effects pertinent to cognitive dissonance can be used to achieve improvement if detected and addressed in a timely manner (Adams, 2016). Unfortunately, neither of the suggested effects have been sufficiently studied to be incorporated into practice, and the majority of the existing literature on the matter is only marginally applicable to the area of leadership directly.

Therefore, it is necessary to conduct a study that would address the outlined issues directly in order to improve our understanding of the matter, including the most likely causes of cognitive dissonance, its exact effects on leaders and their teams, and the possible ways to mitigate its adverse effects, if any. In addition, the research would allow us to establish the relevance of the existing findings from areas marginally related to the topic, which would allow using them for establishing direction and formulating questions for future studies in the field of leadership.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to establish a connection between inner conflict and cognitive dissonance in leaders, determine its effects on leaders’ teams, and outline approaches that could minimize the effects through conscious effort. A descriptive study was selected as a suitable research design since it allows for a relative flexibility of the inquiry process. A qualitative survey was chosen as an instrument for data collection.

The survey includes both open-ended and close-ended questions to make sure that the issues overlooked in the design process could be identified during the analysis stage. The study is to be performed through an online tool with basic analytical capabilities, which is expected to decrease the time necessary for analysis without compromising the reliability of the results, provide maximal convenience for the participants, and maintain anonymity and privacy of the data.

The findings of the proposed study are primarily exploratory in nature. Therefore, its main goal is to improve the current understanding of the cognitive dissonance in leaders and its effects on organizational culture on a large scale. By extensions, this would allow future researchers to obtain clearer direction for their studies and get a clearer picture on the relevance of certain aspects of cognitive dissonance in the workplace. Finally, it is possible that the data analysis would reveal the previously overlooked issues that require closer examination.

Literature Review

The success of leaders in the workplace depends to a certain degree on their emotional state. From the purely psychological perspective, the confidence, involvement, and determination of the individuals depend on their emotions, with negative ones predictably leading to decreased productivity. For the leaders, however, the effect is greater since one of their areas of responsibility requires them to set an example for their team.

Understandably, when leaders are experiencing positive emotions, the resulting improvements are much more visible. In addition, the readiness to engage in problem-solving activities and challenging tasks increases in the teams with optimistic leaders and yields better results (Noruzy, Dalfard, Azhdari, Nazari-Shirkouhi, & Rezazadeh, 2013). Finally, the positive attitude transmitted by the leaders boosts trust within the team, minimizes blame culture, and promotes collaboration and openness within a team.

Cognitive dissonance is a known factor that influences the emotional state of individuals. Moreover, for leaders, it also has an adverse impact on the decision-making capacity, both as a result of the undermined confidence and because of the internal conflict of values that disrupt the clarity of decision. Similarly, cognitive dissonance influences the trust between the leader and its team members.

On the conscious level, it introduces uncertainty by confusing the communication. On the subconscious level, it can create an impression of insincerity and aggravate or trigger interpersonal issues within the team. Simply put, cognitive dissonance has a profound negative effect on the team entrusted to an impacted leader.

The following literature review explores the current sources with the aim of obtaining the recent information on cognitive dissonance and its characteristics. Next, it provides information on its effects on individuals, groups, and social environments. Finally, it outlines the most likely effects that cognitive dissonance may produce in the workplace.

Cognitive Dissonance

Introduction

Dreaming and high aspirations are an essential component of success in life. Currently, imagination and ambition are promoted in individuals from an early age to ensure that it serves as a source of inspiration and creativity throughout life. At the same time, however, the process of growing up inevitably reshapes the ideas about the desirable results, mainly by introducing previously overseen limitations.

In addition, the social component of human activities introduces the determinants of what is considered “appropriate behavior.” As a result, a distinction is formed between dreams and realistic goals, and individuals adapt to the conditions by applying this frame of reference to new ideas and goals. According to Warren and Hale (2016), this is done as a safety measure. More specifically, humans prefer reaching a moderate result without taking risks of failing in the process to gambling and expecting a higher reward. In addition, this provides protection from embarrassment resulting from peers’ reaction to perceiving something that is considered unlikely as a real and feasible opportunity (Lerner, Li, Valdesolo, & Kassam, 2015).

In other words, they practice conformity in order to ensure that they are accepted in the social environment, where the norm is an important factor. Despite the evident advantages of such approach, numerous examples exist of people achieving outstanding results despite a widespread belief that their goals are unrealistic and belong to the realm of dreams. In this context, cognitive dissonance serves as means of retaining inspiration without compromising social status. Thus, understanding cognitive dissonance can reveal not only its adverse qualities but also illustrate the means of coping with them.

Definition

The most widely accepted definition of cognitive dissonance is the uneasiness people experience when they come across knowledge that goes against their established ideas, ideals, or beliefs (Festinger, 1957). Importantly, both the initial and the new information needs to be convincing enough for the individual to perceive it as true rather than dismiss it outright. Each time this conflict occurs, the person starts feeling psychological discomfort that goes away once the dissonance is eliminated (Wicklund & Brehm, 2013).

According to Festinger (1957), this feeling of discomfort is a primary motivation that drives the individual’s determination to resolve the conflict. The most recognizable way of doing this is dismissing a dissonant condition. However, it is also achievable through weighting the dissonant cognition and assigning value to them, or adding cognitions that strengthen the position of one of the conflicting beliefs in order to minimize the value of the competing one (Chang, Solomon, & Westerfield, 2016).

The discomfort resulting from cognitive dissonance is observed regardless of the possibility of undesirable consequences. In other words, people are reluctant to engage in unfamiliar or conflicting behavior even when no apparent harm can be expected in the end (Harmon-Jones, Brehm, Greenberg, Simon, & Nelson, 1996). Therefore, the presence of conflicting notions is a sufficient condition for the creation of cognitive dissonance while the threat of a negative effect is optional.

Foundation of the concept

From the historical perspective, the concept of cognitive dissonance can be traced back to implications made by Freud. One of the principal assumptions in Freud’s works is the pursuit of personal needs as one of the primary drivers of human behavior, operating primarily on the subconscious level (Weiner, 2013). The impact of unsuccessful fulfillment of needs accumulates in sub-consciousness and continues influencing the lives of the individual without being acknowledged.

In many cases, these traumatic experiences obtain significant weight and may become dominant in the decision-making process. It also implies that the positive resolution is less likely since the driving force is based on avoidance of the negative rather than the pursuit of the positive. In most cases, these unfulfilled needs are undetectable without a designated effort. However, once the individuals become aware of their unfulfilled needs, they can exercise better control and consciously seek for improvement by targeting the areas where the said discomfort can be alleviated in the most effective way.

Internal conflict

Another important addition to the theory of cognitive dissonance is the concept of internal conflict introduced by Festinger (1957). According to Festinger (1957), cognitive dissonance is the unpleasant feeling that arises as a result of conflicting beliefs. Importantly, these beliefs are not directly acknowledged by the individual – instead, they create a dissonance without being critically examined and logically processed, which parallels them to the unfulfilled needs discussed above. One of the best-recognized sources of internal conflict is the clash between the preconceived notions (often, but not necessarily, acquired early in life) and the newly encountered information that is equally substantiated and/or convincing.

However, it is as likely to occur as a result of socially unacceptable behavior or the violation of socially imposed norms or expectations. The effect of cognitive dissonance is cumulative and depends not only on the significance of any two conflicting notions but also on the number of the conflicts experienced over a period of time (Gamble & Gamble, 2013). As with the unfulfilled needs described by Freud, the awareness of the internal conflicts provides the person with an opportunity to redirect his or her actions and deliberately address the conflict with the aim of improving the emotional state.

From the information above it becomes apparent that cognitive dissonance is a state rather than a discrete phenomenon and despite residing in the domain of subconscious can be successfully addressed through conscious effort. For an individual in a position of a leader, such possibility becomes an important component of professional practice, in particular, because it has a significant impact on the decision-making process that determines the outcomes for other people.

For instance, some of the internal conflicts may initiate and sustain affirmative behavior, where an ongoing streak of poor decisions or inappropriate actions can add up and eventually obtain a self-fulfilling quality. On the superficial level, the impacted individuals will get consecutive confirmations of their incompetence, lack of proficiency, or “bad luck” which will eventually take effect of a vicious circle.

However, once they acknowledge the existence of unfulfilled needs and internal conflicts, they can address the said conflicts and amend the situation both for themselves, and, in the case of leaders, for their teams. Importantly, the interpretation of the causes of the conflict and the involved factors requires profound understanding of the matter as the majority of variables differ based on the personal characteristics and individual experiences (Willingham, 2014).

Dissonance reduction

Once the dissonance is acknowledged and sufficiently understood, it can be minimized. According to Festinger (1957), this can be achieved in two general approaches. First, through elimination of the behaviors that contradict the established beliefs, or second, through the review and adjustment of beliefs in attempt to bring them in concordance with the required behavior. The easiest example is a situation where an individual believes in a certain kind of virtue (e.g. the trust among peers) and finds out that this virtue conflicts with the requirements of their workplace environment (e.g. the necessity to report the violation of safety conditions by a co-worker).

In this situation, the person may perceive the report as “snitching,” which is obviously a breach of trust. Thus, two outcomes are possible. The person may review their criteria for trust, contrast them with the rationale behind the practice of reporting the violations, find the latter more reasonable and convincing, find their previously held notions regarding trust as obsolete or incompatible with reality, and embrace the newly introduced behavior of reporting.

This would be an example of adjusting the beliefs to the demanded behavior. Alternatively, the person may find the requirement incompatible with their moral code and, as a result, choose to withhold the information, effectively disobeying the directive but preserving personal integrity. In this scenario, the actions are changed to eliminate the discomfort resulting from the actions that conflict with the values and beliefs held by the subject. Until the resolution is reached, the individual continues to experience discomfort that motivates them to arrive at the meaningful conclusion.

In addition to a conclusive resolution, the dissonance can be minimized through one of the several approaches, including justification and denial. For instance, the people who have a subconscious desire for power may feel frustrated upon discovering their inability to exercise authority over others or reach the social status that provides them with the opportunity to do so. As a result, they can start perceiving power as “corrupting” and not worthy of being pursued.

They then start seeking (often subconsciously) information that confirms their belief (Ravven, 2013). At the same time, the evidence to the contrary is either ignored or actively challenged. By doing this, they are able to avoid the conflict between their unfulfilled needs and the reality through denial of the benefits derived from their desired position.

According to Adams (2016), the existence of inner conflicts increases our capacity to resolve problems by prompting us to examine the issue critically. Thus, the suppression or denial of inner conflict is inefficient and usually requires resources that could have been otherwise spent on developing a constructive solution for the problem. Therefore, the discomfort associated with inner conflict should not be dismissed – instead, it must be carefully examined to produce a feasible solution (Adams, 2016).

Research

One of the most recognized case studies of cognitive dissonance is the book “When Prophecy Fails” by Festinger, Riecken, and Schachter (2013). In the book, the author describes the UFO cult led by a leader who prophesized the end of the world and claimed that the membership in the cult could provide the possibility of salvation. The case was especially interesting because the validity of prophecy could be confirmed through simple observation since it was predicted to occur on December 21, 1954.

After the identified date passed with no observable effects, the group was suggested an explanation by their leader that the spiritual purity of the group was strong enough to prevent the disaster (Festinger et al., 2013). The explanation was immediately and uncritically accepted by the group. From the psychological perspective, the described situation is consistent with the scenario of justification, where the information that challenges the pre-held notion (the absence of the apocalypse) not only failed to undermine the faith but was used to strengthen the beliefs of the members. In other words, the cognitive dissonance was minimized through justification.

Further studies revealed that the effect becomes more prominent when the notion is disclosed publicly prior to being challenged (Steg, Keizer, Buunk, & Rothengatter, 2017). In other words, the individuals tend to stand by their beliefs and find justification for them more readily when their peers are familiar with their stance. This effect is strong enough to override the conscious effort of suppressing it – that is, the individual tends to seek for ways of decreasing dissonance even after being pointed to the fact of them doing so.

In the context of the organization, it is possible to imagine the situations in which the described effect could result in either positive or negative outcome, depending on the concordance of values and beliefs held by the leaders and actions required by the organizations.

Organizational Implications

The growing intensity of the contemporary business environment puts forward numerous demands to organizations. Flexibility and adaptability become more important as the dynamics of organizational development become a crucial factor in the light of high competition (Nandakumar, Jharkharia, & Nair, 2014). Another aspect that is uniformly pursued regardless of the industry segment is innovation – the ability to find improvements for existing operations as well as introduce new ones with more value (Anderson, Potočnik, & Zhou, 2014).

Naturally, these expectations are equally applicable to the leaders involved with the organizations. Interestingly, both flexibility and innovation necessitate changes in established behaviors and operations. Therefore, it can be safely assumed that they open up the possibility of inner conflict and, by extension, lead to cognitive bias (Verma & Anand, 2014). Besides, leaders deal with organizational members, each of whom has their own set of values.

Thus, in addition to the dissonance created by the organization-wide changes, leaders are exposed to small-scale inner conflicts on a daily basis. Finally, it should be acknowledged that dealing with workplace conflicts is often listed among the responsibilities of the leaders, and it is reasonable to expect that such activity further increases the likelihood of inner conflict.

From the organization-wide perspective, cognitive dissonance among leaders presents several possible threats. Most prominently, in the situation where the direction taken by the company is perceived by the leaders as undesirable, or the new objective looks unrealistic, they might develop an inner conflict. In this situation, a leader might still come up with a viable plan of actions but will fail to deliver the desired result.

One of the possible reasons is the fact that on the subconscious level, he or she would seek consonance between the professional values and the demands placed by the company. On the superficial level, the activities of such leader would be hardly distinguishable from those of a consonant one unless the results are taken into consideration (Wicklund & Brehm, 2013). Most likely, the reluctance to embrace new behavior will be unnoticed by the leader as well unless he or she is familiar with the issue.

From the team-wide perspective, cognitive dissonance can undermine the emotional climate within the team. The easiest example is the situation where the leader is required to choose between options that each has its potential disadvantages for the team. However, once the personal values and beliefs come into play, it becomes possible that the decision would be made in favor of a more appealing alternative rather than the least controversial or the most beneficial one (Weiner, 2013).

In this situation, the leader will avoid the unease of making a dissonant decision at the expense of the discomfort, and, possibly, the integrity, of the team. As with the previous example, such decision would be subconscious, which excludes the possibility of a reasonable choice. Thus, in both cases, inner conflicts in leaders pose certain risks to workplace environment and organizational productivity unless addressed properly.

Related Research

Despite the evident importance of the concept of cognitive dissonance in leaders, the topic has not been researched directly. However, numerous studies exist that explore related areas and are thus indirectly connected to the current study. For instance, the effects of cognitive dissonance on various aspects of workplace environment are well-represented in the scholarly literature.

A review of managerial research conducted by Hinojosa et al. (2017) revealed that the authors of management studies often recognize cognitive dissonance as one of the variables but rarely integrate it consistently into the research design. As a result, the findings of the researchers usually lack accuracy and often use a distorted or incomplete understanding of the concept. As a result, such studies are only tangentially applicable to the cognitive dissonance theory and its effects. Simply put the majority of the studies have deviated from the core concept significantly enough to devaluate their contribution and, in some cases, render it useless (Hinojosa et al., 2017).

Of the few researchers that approached the theoretical background of cognitive dissonance responsibly, most have only a marginal connection to the area of leadership. For instance, a study by Dechawatanapaisal and Siengthai (2006) explored the effect of cognitive dissonance in the workplace.

Specifically, the researchers studied its effects on learning work behavior. The research team concluded that the psychological discomfort resulting from cognitive dissonance significantly undermines the ability of employees to receive and comprehend new information during the period of transformation in the organization (Dechawatanapaisal & Siengthai, 2006). Interestingly, effective HR practices were shown to mitigate the effect, both by decreasing discomfort and minimizing the unpleasant emotional states and by enabling employees’ learning behavior.

Admittedly, the study is only marginally related to the topic of the current research since the subjects are employees rather than leaders, and, therefore, the obtained results do not describe the transmission of the effects onto the involved teams – instead, it directly addresses the issue of cognitive dissonance in workers. However, the findings obtained by the researchers correlate with the general implications observed throughout the academic literature.

First, the study confirms the suggestion that inner conflict produces enough negative emotions to hinder organizational performance. Admittedly, the study focuses on learning behavior, so the possibility remains that other workplace activities experience the effect on a different scale. However, it is also reasonable to expect that despite the difference in magnitude, the overall effect of discomfort and psychological agitation remains negative throughout the field.

Second, the mitigation achieved through effective HR practices is consistent with the suggestion that the inner conflict can be successfully resolved and its adverse effects mitigated by conscious effort. Thus, despite being of secondary significance to the research at hand, the study by Dechawatanapaisal and Siengthai (2006) confirms the implications made by the research team.

A study by Lopez and Picardi (2017) explored the effect of perceived equity in the workplace on the cognitive dissonance in employees. According to the authors, individuals tend to adjust their workplace behavior in accordance with the sense of fairness. Thus, the cognitive dissonance between the requirements of the organization and the perceived inequity leads to discomfort and, by extension, the decline in productivity (Lopez & Picardi, 2017).

Interestingly, from the cognitive dissonance theory standpoint, such decline in motivation signals the existence of potential motivation. The researchers found a relationship between the reported dissonance and the decline in productivity, with organizational culture being cited as the most common reason behind the perceived inequity (Lopez & Picardi, 2017).

These results are also consistent with previous findings highlighted in the literature review but are only of marginal importance for the current study since they describe the effect of cognitive dissonance on employers. While it is reasonable to expect that inner conflicts in leaders will eventually lead to similar outcomes in their teams, this implication needs to be confirmed separately, and its effects weighed against other probable scenarios. Therefore, the study is to be used to substantiate the significance of the current research and to illustrate the possible sources of cognitive dissonance.

Summary

Since its introduction by Festinger, the concept of cognitive dissonance has become an important part of organizational culture. According to the current understanding, it has a profound effect on the behavior of both leaders and employees within the organization. The current academic consensus holds that the effects of cognitive dissonance on productivity are generally negative, although its impact can be reduced through acknowledgment and conscious effort.

This fact leads some experts to believe that when addressed properly, the inner conflict can actually yield positive results in the form of additional motivation and assistance in critical approach to problems. However, despite the wide recognition of the importance of the concept, the issue of cognitive dissonance in workplace remains under-researched. In addition, certain areas, such as cognitive dissonance in leaders, remain overlooked despite their apparent importance for the organization.

Methodology

Research Questions and Hypotheses

Considering the information gathered in the literature review section, several gaps in current knowledge can be identified that demand a closer examination. Specifically, it is necessary to understand how inner conflict felt by leaders is related to the cognitive dissonance experienced by them, and whether it has an impact on their interaction with workplace teams entrusted to them. The most probable anticipated cause of the adverse impact is the stress and anxiety felt by a leader and the direct and/or indirect projection of stress on team members.

The study also aims at outlining the most feasible approaches to addressing the adverse effects of cognitive dissonance through conscious efforts ranging from increased awareness and understanding of the causes of stress to specific reflective practices intended to minimize the possible negative outcome.

Three research questions were formulated to address the identified areas.

- Q1. Is there a relationship between inner conflict and the emergence of cognitive dissonance experienced by leaders in the professional setting?

- Q2. Is the experience of cognitive dissonance in leaders reflected in their relationships with teams as a result of projecting their stress?

- Q3. Can the adverse effects of cognitive dissonance in leaders be mitigated through conscious efforts?

In correspondence with the research questions above and considering the information obtained from the literature review, three research hypotheses were formulated:

- H1. There is a perceived positive relationship between the feeling of inner conflict and the experience of cognitive dissonance as reported by the leaders.

- H2. The experience of cognitive dissonance can be traced to the relationships between leaders and their teams through the projection of stress onto team members.

- H3. The adverse effects of cognitive dissonance can be mitigated through conscious efforts (e.g. awareness of the reason behind the discomfort, reflective practices, and willingness to actively address the underlying cause of the issue).

Research Design

Research design chosen for the study was a descriptive research, conducted in the form of a survey. Such design has several benefits critical for the formulated research question and provides advantages with regard to the existing knowledge on the matter. First, it is consistent with the formulation of the research topic based on the previous experience. As was detailed in the literature review, the issue of cognitive dissonance as a result of the inner conflict is broadly represented in the contemporary literature and lacks depth in the form of concrete definitions or substantial findings.

While such amount of information does not allow predicting the results with a degree of certainty, it is sufficient for formulating a qualitative research question. In addition, the existing studies usually lack the necessary context that would improve our understanding of the issue. The reviewed sources commonly explore a specific area of organizational activity without considering a multitude of the possibly relevant factors.

Qualitative studies usually have an advantage of broadening the understanding of the concept, and possible revealing previously overlooked details. Specifically, the current research is expected to outline numerous aspects of inner conflict in leaders, and since no concrete data exists that would allow weighting the significance of the factors commonly believed to cause the cognitive dissonance, it would be reasonable first to obtain an overall picture based on the perspectives of the leaders in the field. Next, the social constructivist perspective common for qualitative research is consistent with highly personalized nature of cognitive dissonance.

As was described above, cognitive dissonance strongly depends on the sets of values and beliefs possessed by each individual, and while some of these can probably be generalized on the basis of social norms and workplace ethics, others will certainly be unique for each individual. Therefore, the social constructivist paradigm, which considers multiple perspectives in order to reach a conclusion, can be used to process the obtained information.

Another advantage of the qualitative research design is the possibility to work with the small sample size. First, this complies with the time and resource restrictions characteristic for the project. Second, the lack of well-established theoretical basis (aside from the extensive information on the theory of cognitive dissonance in general) necessitates the use of open-ended questions that can yield more information but require more time to analyze. In this context, the smaller sample size would mean affordable time spent on the analysis without sacrificing the quality or reliability of data.

The data will be collected by administering an online survey. Since the survey contains both close-ended and open-ended questions, the obtained responses would be analyzed differently. For the close-ended questions, the data will be processed using the functionality of the used software which would also generate a visual representation of the analysis. The responses to the open-ended question will be reviewed individually with the aim of defining common themes and areas highlighted by the responses.

Once the themes are determined, the responses will be categorized in order to identify the most common variants. It is expected that certain areas would match those pertinent to the close-ended questions. However, it is reasonable to expect new insights derived from the responses highlighting the overlooked variables.

Given the goal of the research team to explore the area that is insufficiently covered in the existing literature, it is reasonable to typify the study as exploratory. Such type focuses on the discovery of ideas and identification of specific objectives for further studies rather than the generation of the statistically significant data. First, such research type does not require the availability of robust findings by previous researchers. Second, it provides an opportunity to provide the sense of direction for future studies, which is useful considering the feasibility of the topic. Finally, while such type of study does not provide statistically measureable results, it can deepen the understanding of the problem by offering richer information from the participants.

Operational Definitions

The formulated hypotheses contain several independent and dependent variables that need to be defined to eliminate ambiguity and streamline the process of analysis.

Independent variables

The two main independent variables involved in the study are inner conflict and cognitive dissonance in leaders. The inner conflict can be defined as the conflict of values experienced at a personal level (Adams, 2016). Cognitive dissonance is a feeling of discomfort that appears when individuals encounter information that contradicts their preconceived beliefs, notions, or values (Festinger, 1957).

For the third research question, the efforts intended to mitigate the effects of cognitive dissonance are considered an independent variable. These efforts are defined individually by the respondents and can include any activity that is expected to help the leaders cope with inner conflict effects. Since the study explores the perceived effects of cognitive dissonance as reported by the participants, all variables will be measured based on the assessment of the respondents via five-point Likert scale and true-false questions.

Importantly, the exploratory nature of the study opens up the possibility of identification of the activities overlooked by the researchers (through open-ended questions), in which case the measurement will not be possible.

Dependent variables

The dependent variables relevant for the study include the adverse effects experienced by workplace teams and the mitigation effects of the conscious efforts. The former is any effect that can be conclusively linked to the stress projected by the leader and affecting team performance. The latter is the perceived improvement following the practice that results in the elimination of discomfort and is not achievable otherwise. As with independent variables, these will be measured based on the reports by the respondents and evaluated on the five-point Likert scale.

Participants

The analysis will be based on the primary data obtained directly from the participants. In order to ensure the relevance of the information, the participants were chosen from the individuals working in management positions. The educational setting was chosen for sampling, with ten schools determined as a source of the sample.

Specific criteria were devised to ensure the suitability of the sample for the study. First, the participants had to be involved in working with teams of employees. As such, the top manager segment was excluded to ensure that the participants were closely interacting with employees on a daily basis. Such criterion ensured that their responses covered not only the organizational aspect of the cognitive dissonance but also the team management side.

By extension, the results obtained in this way would be applicable to the effects experienced by the team members involved with the leaders who undergo inner conflict. Next, the participants were required to have at least two years of experience in their current position. Such condition would increase the likelihood of their exposure to the inner conflict and thus actualize their knowledge on the topic. To further exclude misinterpretation, the participants were briefly interviewed on the matter of their familiarity with the concepts and theories used to construct the survey, and the identified misinterpretations and inconsistencies in knowledge were addressed.

In other words, additional measures were incorporated into the sampling procedure to make sure that the participants have sufficient understanding of the issue and their responses thus have sufficient relevance for the study. Finally, the sample was retrieved from the organizations that have undergone at least a minor transformation in the period that coincided with the participants’ experience in the managerial position.

This condition would increase the likelihood of them dealing with cognitive dissonance. The change in organization is a massive source of inner conflict both in managers and in employees, so it would be reasonable to expect that such setting would serve as a cause of cognitive dissonance both directly (by introducing the requirements that may conflict with the personal values) and indirectly (by initiating the conflicts in team members).

The estimated sample size sufficient for the project is twenty individuals. The recruitment of the sample will be performed by contacting the administration of the chosen schools and explaining the purpose of the study as well as the criteria of the sample. Once the recommendations of the administration are obtained, the managers eligible for participation will be contacted via e-mail and briefed on the purpose and conditions of the study.

At this point, personal referrals will be used to increase the sample size and include those overlooked by the administration. Those who agreed to participate will be contacted on the phone for further clarifications on the safety and privacy issues pertinent to the study, and their formal consent will be obtained. Once the definitive list of participants is constructed, the surveys will be administered via e-mail, with ten days allocated for completion, after which the number of responses will be verified using the functionality of the online tool to estimate the response rate. The tool gathers data anonymously, so only the percentage of the responses will be derived.

The study requires the participation on the voluntary basis, so no compensation will be available for the participants. The candidates will be explicitly notified on this during the initial contact via email. The information will be confirmed in the telephone conversation.

The online tool used for the study incorporates several measures intended to protect the participants’ privacy. While the resource registers the IP address of the participants, this information is used internally to ensure the integrity of data and is not available to the researchers, participants, or a third party. All of the data is encrypted and transferred through secure channels. The results are properly anonymized.

The account is protected with a strong password to exclude the possibility of a leak. The sensitive data gathered during sampling is encrypted and stored using open-source software. This document is handled separately and not used in the analysis of the data to exclude accidental disclosure. The participants are informed about the protective measures as well as the probability of data loss due to malfunction of the equipment or a deliberate attack.

Instruments and Materials

A survey was developed to establish the existence of a relationship between the inner conflict and cognitive dissonance, identify possible effects of cognitive dissonance on leaders’ teams, and explore the potential ways of mitigating the effect. The survey consisted of twenty-nine open-ended and close-ended questions and aimed solely at the leaders within the organization. Since the survey was intended for online administration, the questions were intended to be as short as possible without sacrificing the clarity and precision (15 words per question on average).

The survey was administered to the participants remotely via email and text messaging. The number of responses was verified to exclude the possibility of inconsistencies. The combination of open-ended and close-ended questions was chosen in accordance with the exploratory nature of the study since it offered a broader overview of the possibly useful techniques without significantly increasing the time necessary to process the data.

The online form of the survey served two purposes. First, it allowed for a more convenient administration and provided the participants with the possibility to choose a suitable schedule. While it also increased the time required for data collection, such drawback was acceptable considering the small sample size. Second, the data processing capabilities of the online tool minimized the time and resources required for data analysis. While the functionality of the platform is relatively limited, the accuracy of the analysis was acceptable for the exploratory qualitative study.

After the questions had been ready, they were reviewed by a group of peers for clarity of statements and the presence of errors. Several questions were re-written to eliminate possible misreading and multiple interpretations. The questions were also submitted for review by a manager with the relevant experience to verify their applicability for the chosen topic. Once the text was finalized, it was entered into an online tool, after which the survey was administered to three peers to check whether it worked as intended. Once the functionality was confirmed, the collected data was erased to ensure the integrity of the results.

Procedure

The data will be collected remotely by sending a link to the survey via email or the messaging system of participant’s choice. Ten days will be allocated for participants to leave their responses. The timeframe will be specified prior to the data collection and included in the reminder accompanying the link. After ten days, the survey results will be locked so that no further responses could be added. The number of returns will be matched to the initial participants to establish a response rate.

The data on responses to close-ended questions is expected to be available instantly via tool’s analytical tools. The responses to open-ended questions will be handled separately by grouping them into meaningful categories and assigning representative codes. The coded responses will then be quantified and included in the final results.

Results

Introduction

The concept of cognitive dissonance covers an important aspect of the organizational development process. More specifically, it accounts for the causes of inner conflict in the impacted individuals and describes the most likely effects of the process. However, despite its far-reaching implications in the organizational setting, it has not been covered in the specialized academic literature, and the existing findings do not align with the theoretical understanding, most likely due to the lack of uniformity of definitions (Hinojosa, Gardner, Walker, Cogliser, & Gullifor, 2017).

The issue is especially relevant when applied to leadership practices since leaders are more vulnerable to inner conflict due to the range of their responsibilities and close contact with the employees.

Finally, their exposure to the effects of organizational change makes the possibility of adverse effects of cognitive dissonance especially relevant. The purpose of the study is thus to establish a connection between inner conflict and cognitive dissonance in leaders, determine whether it affects their team, and identify the techniques that have the potential to minimize the undesirable effects. Consequently, it would also be possible to identify the alleged positive effects of cognitive dissonance on the organizational performance.

Since the existing research on the matter is relatively scarce and inconclusive, the study is exploratory in nature. For this reason, the qualitative method was chosen as a research design. The data collection was performed through a survey consisting of both close-ended and open-ended questions. The latter were expected to broaden the scope of the inquiry and possibly locate the techniques overlooked by the research team and not included in the survey.

The survey was designed using an online platform and administered online via email. The participants were selected based on a set of criteria intended to ensure the relevance of their experience on the matter. The analysis of data was performed in two ways. The responses to close-ended questions were analyzed using the capabilities of the online tool, which provided a reliable result in a timely manner. Admittedly, the tool produced only the most basic data, such as the percentage of responses for each question. However, such approach is sufficient for the qualitative research design selected for the project and is acceptable considering the size of the sample.

The responses to the open-ended questions were handled manually. Each set of responses was reviewed in order to identify main themes. The themes were then refined through careful examination, during which similar groups were merged while sufficiently broad ones were split for greater precision. Each response was then assigned the category it best aligned with. After this, the results were quantified and their percentage calculated. The results were converted to graphs for clearer representation.

Descriptive Data

Only the gender demographic data was collected during the survey, since the focus of the study, the narrowly specified criteria, and the convenience sampling process did not permit meaningful deviations in such areas as occupation, education, income level, and age. In addition, the sample was relatively small, and its further disaggregation could lead to the inability to draw meaningful conclusions.

Twenty-one participants returned the responses, of which one did not complete the survey beyond the first question. Thus, the retention rate was 95%. Ten male and ten female respondents participated in the survey, which indicates an even distribution characteristic for the field and thus suggests that the sample was representative. All respondents displayed their satisfaction with the job, either agreeing (42.9%) or strongly agreeing (57.1%) with the statement that they love their job.

The diverse views were always considered in 35% and frequently considered in 50% of the cases whereas only 15% of the responses reported a moderate result. Consequently, 85% of the respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that their workplace could be considered a dynamic and changing environment. The overwhelming majority of the leaders (85%) believe that they succeed in establishing good relationships with the team most of the time. 25% of the participants did not recall changes that contradicted their beliefs and values, 40% considered it a rare occasion, and 35% stated that it happens sometimes.

However, 30% of the respondents reported significant difficulties in accomplishing goals that do not align with their values whereas only 15% stated they have no issues with such scenario. Interestingly, a significantly smaller proportion of the respondents (25% total) agreed that communicating such goals to their teams was challenging for them while 10% reported no difficulty at all and 40% found its effect negligible.

The completion of a conflicting task yielded greater emotional satisfaction often to 30% of the respondents whereas 60% reported that the effect was only observed sometimes. The majority of the respondents (55%) disagreed with the notion that their values could be disregarded when they came into conflict with the goals of the change and its expected benefits. The observation of the negative impact of the conflicting situation on the team was relatively even, with 20% reporting no observed effect, 20% stating that it happened most of the time, and 55% considering it a rare occasion.

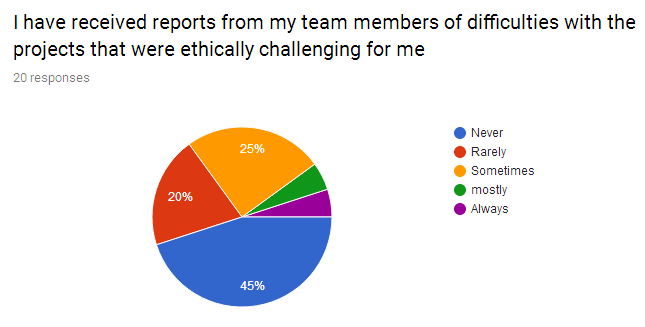

However, in 45% of the occurrences, no reports were received from the team that could be linked to the ethical conflicts experienced by the respondents, and only 45% reported it as occasional (only ten percent of the respondents reported frequent reporting on the matter). None of the participants agreed that the observed adverse impact was the result of their reaction. However, 45% gave a neutral answer. None of the approaches meant to reduce the discomfort identified by the survey was reported by the majority as definitively effective, with all eight options receiving a 25 to 57.9 percent of responses characterizing it as moderately effective and 21.1 to 55 percent as mostly effective with no evident advantage.

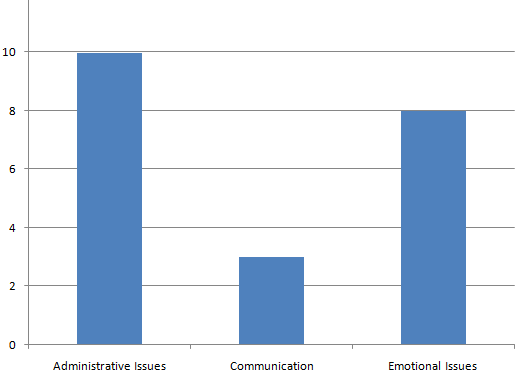

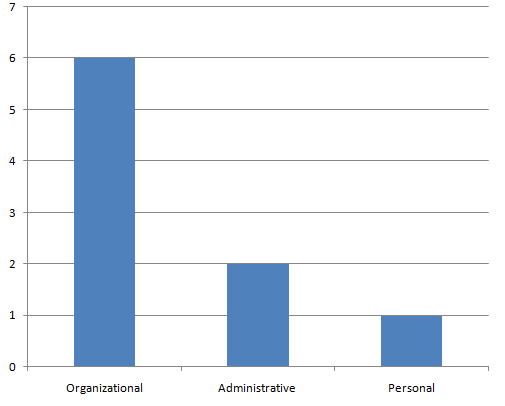

The open-ended questions were categorized and resulted in the following frequency analysis findings. The personal strengths were based on compassion and care in 35% of the cases, dedication in 60%, and teamwork in 20%. The major personal issues were of administrative origin in 50% of responses, communication in 15%, and emotional in 40%. The needs of values identified by the participants were organization-oriented in 50% of the cases, team-oriented in 35%, and based on personal determination in 20%.

The definitions of ethical leadership included the concept of communicating values in 55% of responses, aspect of teamwork in 25%, and corporate values in 20%. The challenge of ethics was related to organization’s issues in 30%, the management in 10%, and personal conflict in 5% (55% could not come up with an example). The existing values were retained 20% of the time and overturned by new goals in 25%.

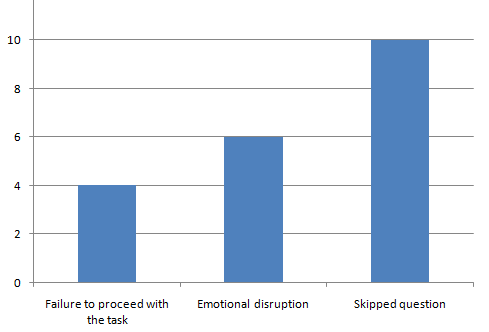

The conflict experience was based on the interaction with the management 45% of the time and with the team in 20% of the instances (35% blank responses) and resulted in emotional disruption in 30% of occurrences compared to the loss of productivity in 20% (50% blank responses). The common complaints voiced by the team were related to lack of appreciation 30% of the time and the workflow disruption in 45% (25% blank). Finally, the helpful techniques were mostly based on communication (35%), self-reflection (30%), and additional time allocation (10%) (35% blank responses).

Analysis of Research Questions

The first research question deals with the connection between inner conflict in leaders and the emergence of cognitive dissonance. While it is not explicitly stated in the survey, several questions provide the data sufficient for establishing a link. For instance, the overwhelming majority of the core issues impacting the leadership practices could be traced to the conflict between the goals set at the organizational level and the output of the participants and were associated with significant emotional discomfort (85%).

The conclusion is further corroborated by the fact that the majority of the respondents consider their workplace environment highly dynamic, which increases the chance of introducing the conflicting values and triggering cognitive dissonance. Next, the sources of challenged ethics (question 9) and the conflicting experience associated with it (question 14) originate primarily in the new requirements imposed by the organization and related to change, thus requiring the conflicting issues taking place.

Finally, and, perhaps, most importantly, the difficulties associated with the completion of an ethically challenging task are consistent with the effects of cognitive dissonance. Admittedly, the available data does not allow arriving at a definitive conclusion since there is a possibility that the observed correlation is not attributed to causation. However, the link is also consistent with the theoretical implications of the issue and is corroborated by the findings of the researchers from the related fields (Dechawatanapaisal & Siengthai, 2006; Lopez & Picardi, 2017).

It should also be noted that the establishment of a definitive causal relationship would require a much more focused inquiry and a more appropriate design of the study. Therefore, considering the scope of the project at hand, it is reasonable to accept the available data as sufficient for the support of the hypothesis.

The second research question deals with the effects of the experienced dissonance on the leader’s team. The thirteenth question addresses the issue directly by inquiring on the feelings accompanying the communication of the conflicting values and objectives. Since only ten percent of the respondents considered it a non-issue, it would be reasonable to accept it as a confirmation of the second hypothesis.

Nevertheless, an additional forty percent of the respondents stated that the discomfort was a rare occurrence, which significantly decreases the perceived strength of the influence. Next, more than half of the respondents reported the observed effects of the ethically controversial task on the team as relatively common while only 20% considered them as non-existent and another 25% stated that they are rarely observed.

Importantly, the observations apparently do not match the reports received from the team since almost half of the participants do not receive such feedback at all and only ten percent reported them as frequent.

Thus, it becomes evident that the effects of cognitive dissonance compromise trust between the leaders and their teams and disrupt consistent communication. While the effects of such disruption were not addressed in the survey, they are commonly believed to have a negative impact on the workplace climate and are therefore consistent with the hypothesis that the effects of cognitive dissonance in leaders can be observed in the relationships with their teams. The existence of the link is further corroborated with the effects reported in question 19. Thirty percent of the respondents described the effects as negatively impacting the emotional state of the involved individuals while additional twenty percent characterized the effects as influencing the ability to proceed with the task.

Surprisingly, the reports from the team recalled by 45 percent of the participants included the inability to efficiently participate in change while only thirty percent pointed to the emotional issues (the lack of appreciation being the most common cause). Such results are contradictory, which can be partially attributed to the inability of the respondents to separate the complaints tied to inner conflict from those caused by the unfavorable organizational environment.

Finally, it should be pointed out that the responses to question 21 do not align with the trends derived from the rest of the survey since none of the participants attributed the adverse reaction to their reaction as opposed to that of the team members. It is possible that such inconsistency is explained by the lack of understanding of the question. Specifically, the effect could be interpreted as directly related to the team’s concerns with the issue rather than traced to the leader’s initial reaction.

With the exception of the final question, the findings are consistent with the implications of the theoretical literature on the matter (Lopez & Picardi, 2017). However, the presence of the contradictory findings points to the fact that the conclusions may be subject to misinterpretation by the participants, which undermines the objectivity of the data.

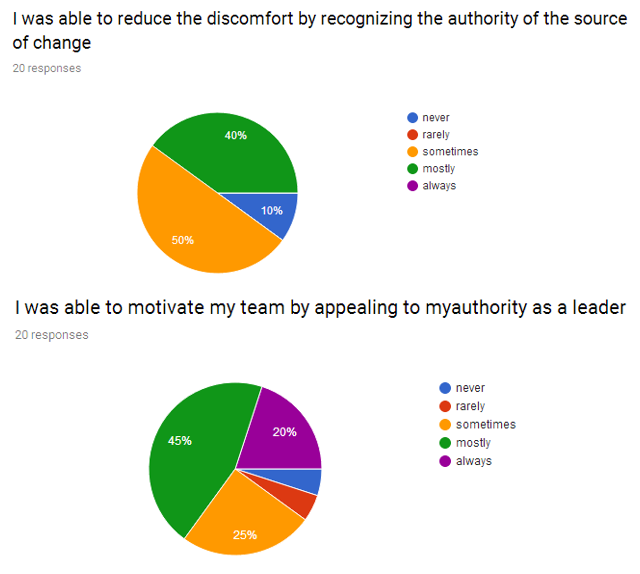

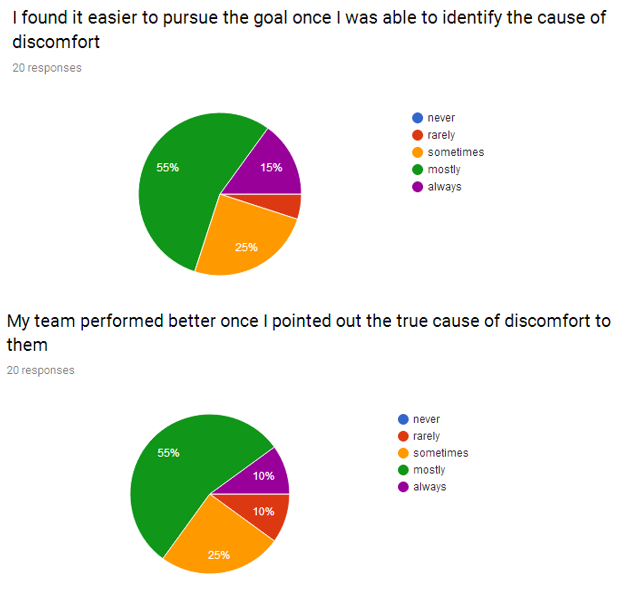

The third research question was expected to outline the feasible approaches to mitigating the undesirable effects. The question was addressed directly in questions 22 through 29, with an additional open question intended to identify the techniques overlooked during the survey design process. Questions 22, 24, 26, and 28 explored the possibility to resolve the dissonance internally while questions 23, 25, 27, and 29 contained the approaches applicable to the team members.

Admittedly, none of the proposed techniques gathered sufficient support to be recommended as a feasible solution. The appeal to authority was reported as more effective for increasing team’s coping capacity than personal one (20% always and 45% often versus 40% often, respectively).

On the other hand, the recognition of the inevitability of conflict as an intrinsic part of the change process was more often used for personal purposes (15% always and 40% mostly) than for the motivation of a team (5% always and 30% mostly). The same can be said about the appeal to the rewarding experience associated with the completion of the objective, which was reported as effective in all cases by 10 percent of the participants and in most cases by 45 percent compared to 15% and 20% for group motivation, respectively. Finally, the identification of the cause of discomfort was cited as effective in all cases (15%) and in most cases (55%) for personal use compared to 10% and 55% respectively for better team performance, making it the most effective technique.

Question 30 was meant to expand the list giving the participants an opportunity to share their approach to the issue. The responses were grouped in three distinct categories – communication (35%), self-reflection (30%), and additional time allocation (10%). Thirty-five percent of the respondents did not provide the answer or provided the information that did not correspond to the requirements. It should also be mentioned that the techniques identified by the participants did not differ significantly from those referred to in questions 24 through 29 and thus cannot be considered additional information.

All techniques were derived from the most common approaches to cognitive dissonance available in the theoretical literature on the matter and the existing studies from the related fields. The results are thus largely consistent with the current understanding of the phenomenon and confirm the applicability of the findings of the previous studies to the area of leadership.

Other Observations

Two important issues are worth pointing out after examining the data. First, the allegations suggested by some theorists that, when addressed in a timely manner, cognitive dissonance can enhance productivity, received no support from the available data. The suggested positive effect of discomfort that accompanies cognitive dissonance was addressed directly in question 15. The majority of the respondents (65%) considered occasional occurrence of the rewarding experience and 5% dismissed it entirely.

Only 10% of the participants found the effect to be consistent. Admittedly, emotional satisfaction is only one of the possible positive outcomes, the other being greater resilience and determination to achieve the goal (Adams, 2016).

However, the relatively small proportion of the reported positive effect suggests that it is either negligible or is not determined by the satisfaction with the outcome. It is also notable that in question 17, 20 percent of the respondents stated that they did not observe negative impact on their teams while working on an ethically challenging task, and another 25 percent considered the effect to be rare. It probably cannot be considered a conclusive finding for disproving the assertion, but points to its weakness.

Second, it should be noted that the manner in which the participants respond to the open questions indicate that at least in some instances the questions have been misunderstood. Most prominently, the responses to Q 9 and Q 14 often contain similar statements despite the fact that they cover different types of experience (inner conflict and team interaction, respectively). Next, at least one respondent provided a detailed description of the rewarding experience associated with the observation of students’ accomplishment, which is clearly unrelated to the techniques for mitigating the effects of cognitive dissonance.

Other responses were detected in the process of analysis that could be coded and assigned category but indicated a possibility that they were the result of misinterpretation. Since the sample used for the study was rather small, the misinterpretation can significantly disrupt the reliability of findings as a single distorted response accounts for five percent of the feedback. The reasons for such discrepancy are unclear since the survey was carefully reviewed and successfully tested prior to administration, producing acceptable responses.

For instance, it is possible that due to the lack of recognition of the phenomenon of cognitive dissonance the participants were unable to disaggregate its effects from those of stress and, by extension, did not employ relevant methods directly addressing the matters. Thus, the possibility of misinterpretation should be acknowledged when arriving at the conclusions.

Discussion

Conclusion

The purpose of the study was to determine whether the occurrence of inner conflict in leaders who participate in the process of change contributes to the emergence of cognitive dissonance and whether the discomfort resulting from it has a negative impact on the leaders’ interaction with their teams. Additionally, the techniques commonly used by the leaders in the workplace to minimize the adverse effects were expected to be identified, and their effectiveness determined.

For the purpose of the study, the negative effects and respective techniques were based on the available theoretical information and the studies from the related fields. The study was exploratory in nature since the effects of cognitive dissonance in the context of leadership are not studied sufficiently, and the existing studies lack the precision of definitions and produce conflicting results (Hinojosa et al., 2017).

The qualitative design was chosen for the study as it aligns with the exploratory nature of the research and allows for an in-depth inquiry into the topic using a relatively small sample. The data was gathered through an online survey administered via email to the leaders working in the educational setting.

The survey included several open-ended questions which were expected to provide additional insights and possibly identify the techniques and approaches overlooked during the construction of the survey. The responses to close-ended questions were analyzed using the capabilities of the online platform and converted into graphs for convenience. The responses to open questions were reviewed in order to identify common themes, arranged into categories, and quantified in order to detect common tendencies.

Interpretation of Findings

The frequency analysis of the close-ended questions allowed us to conclude that the occurrence of inner conflict associated with organizational change was produced the effects consistent with those of cognitive dissonance. The majority of participants agreed that their workplace was a highly dynamic environment and reported emotional discomfort when dealing with an ethically challenging task.

The themes identified through coding of responses to open-ended questions were conclusively tied to the changes imposed at the organizational level and thus associated with the introduction of the conflicting objectives and values. All of the effects determined by the analysis are objectively consistent with those proposed by the theorists as a result of cognitive dissonance (Lopez & Picardi, 2017). Admittedly, the available data allows for alternative interpretations since some confounding variables are probably responsible for at least some of the reported effects. However, the alignment with theoretical literature serves as additional confirmation of the findings and is sufficient considering the scope and exploratory nature of the current study.

The analysis also confirmed the existence of negative effects of cognitive dissonance on the interactions with the team. The leaders identified conflicting values as a significant detriment to workplace climate, communication between team members, and personal psychological state. Most importantly, the responses to both the close-ended and open-ended questions conclusively pointed to the fact that the discomfort associated with cognitive dissonance impairs the ability to achieve the set goals and move in the direction outlined by the organization.

Thus, it becomes evident that cognitive dissonance as a core cause of the emotional and psychological disruption can be viewed as a source of negative impact on productivity and organizational performance. Admittedly, the respondents were not uniform in their judgment, with some dismissing the phenomenon of emotional discomfort as irrelevant for the productivity of their team.

Most prominently, the majority of the participants suggested that the negative effects associated with change can be attributed primarily to their teams, which means that the effects of the discomfort projected by the leaders are either insignificant or nonexistent. However, this perspective should not be considered evidence against the second hypothesis. Instead, it is more probable that the discomfort experienced by the leader influences the team less than the inner conflict experienced by them at the personal level and created through a similar mechanism.

In other words, it is unclear whether the studied effect has a significant contribution to the overall decline of performance compared to other known phenomena such as resistance to change. However, it should be understood that this question is outside the scope of the current study. Since the existence of the negative effects of cognitive dissonance has already been established, it would next be reasonable to explore the identified area and determine whether the relationship has a relatively significant effect.

Finally, several techniques were identified by the participants as effective in addressing the setbacks in performance and restoring the emotional climate. The appeal to authority was more often utilized for resolution of personal conflicts with limited evidence of its effectiveness for increasing team performance. The recognition of the inevitability of conflict, on the other hand, was reported as a more popular component of the effective motivation of the team rather than the tactics used to resolve inner conflicts.

The appeal to the rewarding experience associated with the completion of an ethically challenging task was similarly reported as an approach that is more suitable for team-based interactions than those directed towards personal cognitive dissonance. Finally, the identification of the source of conflict was perceived as effective in more than half of the cases for the motivation of the team with a slightly lower result for personal use.

It also received the greatest proportion of responses characterizing it as the most viable technique. Nevertheless, in all cases, the reported reliability of the outcome of the methods ranged from 25 to 55 percent which does not allow considering it a recommended approach. The techniques suggested by the participants were based mostly on communication with the teams and various methods of self-reflection, with small proportion suggesting allocation of additional time as a solution.

However, it should be pointed out that the majority of tactics suggested in the survey already incorporate communication or self-reflection in some form. In addition, none of the responses reveal enough details of the approach to differentiate it from those suggested in the survey. Therefore, while the open-ended responses can be considered a confirmation of the limited effectiveness of the suggested approaches, they do not offer any additional insights.

To sum up, all three research hypotheses were confirmed by the results of the analysis. However, neither of them received enough support by the data to be considered a reliable solution. For instance, it is evident that some techniques are used by the leaders to mitigate the adverse effects of cognitive dissonance on their team. At the same time, there is no reliable description that could be used to conceive a guideline. Nevertheless, the results provide an overview of the applicability of the generalized theoretical concepts to the domain of leadership and identify the directions for future research as is expected from an exploratory study.

Additional Analysis

In addition to the confirmation of the research hypotheses, several minor insights have been obtained in the process of the analysis. First, the assertion that timely addressed cognitive dissonance could lead to the improvement in organizational performance was not backed by the evidence. Specifically, the concept of the emotional reward enhanced by the presence of the ethical challenge was dismissed by the majority of the respondents. Importantly, such orientation at rewarding experience is only one of the components responsible for the effects as described by its advocates (Adams, 2016).

In addition, the identification of the positive effects of cognitive dissonance was outside the scope of the current study. Nevertheless, its absence from the responses to the open questions suggests that its effect is either negligible or is not recognized by the participating leaders. The latter is especially likely since the scarcity of studies on the matter and the lack of awareness of the effects of cognitive dissonance on leadership practices has been pointed in the literature.

Another observation that requires additional analysis is the existence of inconsistencies between the responses. For instance, the proportion of the responses on the effects of cognitive dissonance does not coincide with the reported observations of discomfort associated with the conflicting ethical values and goals. Next, the participants tend to duplicate and misplace the effects of personally experienced cognitive dissonance and those observed within their teams as a result of the interaction.

Finally, at least one of the responses on the effective techniques for adverse effect mitigation included the description of the perceived reward (unrelated to the question), with several other responses containing elements that suggest possible misinterpretation. It is possible that such inconsistencies are the result of the inadequately formulated questions or the misleading structure of the survey. However, since the survey was reviewed and tested with satisfactory results, it would be reasonable to consider other explanations.

For instance, it is possible that the respondents were not familiar with the concept of cognitive dissonance and were thus unable to differentiate between the emotional setback associated with it from those commonly observed as a result of stress and interpersonal conflicts that are common in the organizations undergoing change. Some of the results obtained during the analysis are consistent with this suggestion, such as the alleged lack of ethically conflicting tasks in the workplace reported by the participants, which does not correspond to the familiarity with the effects they produce. Such lack of awareness is to be expected considering the relative scarcity of the research on the topic. However, the conclusion is mostly speculative and requires additional verification.

Limitations

The study has several limitations that need to be recognized. First, the limited resources and time constraints of the project has resulted in the use of the non-probability sampling. As a result, a considerable proportion of the representative population was not included in the inquiry, which means that the results do not necessarily apply to the entire domain. In addition, all of the participants were chosen from the educational setting.

While it is tempting to assume that such approach resulted in a more focused inquiry, it is also possible that the leadership practices in other settings have an additional set of factors that render the findings of the current study irrelevant. Finally, such sampling technique does not permit estimating the variability of the sample and therefore does not allow identifying possible biases, such as the selection bias. However, it should be emphasized that the inclusion criteria formulated by the researchers prevented using probability sampling without significantly diminishing the number of participants.

Second, the participants were recruited from a small number of organizations. The first step of the sampling procedure involved contacting the administration of the chosen organization in order to facilitate cooperation and get support in the process of selection and recruitment of the participants. Such approach allowed contacting the desired number of participants in the relatively short time and commencing the data collection process without exceeding the available resources. This factor further limited the ability to generalize the findings. For instance, the specificities of change-related processes can differ across the organizations to the degree where the same change in policies will produce a different reaction and encounter different implementation barriers.

Third, there exists a possibility that the questions of the survey were designed with insufficient clarity, which led to confusion among the respondents and compromised the reliability of their answers. While alternative explanations are possible to account for the phenomenon, such possibility should not be overlooked and must be prioritized during the design of the replication studies.

Fourth, some of the responses indicate insufficient familiarity of the sample with the concept of cognitive dissonance and its manifestations in the emotional and psychological state of the individual. Such lack of awareness can be expected considering the scarcity of area-specific theoretical literature on the matter and should be acknowledged in future studies. Specifically, the questions designed with this theoretical gap in mind should describe the effects in question more specifically in order to differentiate them from those caused by stress and other change-related factors.

Fifth, the data was collected from a relatively small sample. This was done primarily to decrease the time necessary for the coding and analysis of the responses to the open-ended questions. However, the tendency of some of the respondents to omit certain questions and the existence of the misattributed responses has led to the situation where a single misplaced response accounted for a five-percent deviation. Combined with the possibly incomplete understanding of the studied phenomenon it is possible to expect the lack of reliability of findings.

Implications for Theory and Practice

From the theoretical standpoint, the findings of the study are valuable primarily as a confirmation of the existing understanding of the effects of cognitive dissonance on leaders in the professional setting. As was explained above, the currently available information allows only for a generalized perspective whereas the specific effects on leadership practices remain underresearched. More importantly, the methods of mitigating the said negative effects are only broadly defined, and their applicability to specific settings can only be determined theoretically. Thus, the results outline the perceived effectiveness of each method for both individual use and interaction with the team and outline the most viable direction for future studies on the matter.

However, the most important implications reside within the domain of practice. The current orientation of the organizations towards sustainable improvement of their operations and seamless innovation as an integral part of their functioning rely on change as a necessary component. Since change often challenges the values and beliefs of the individuals in leading positions by introducing new goals and objectives, it is reasonable to expect the eventual emergence of cognitive dissonance.

As was confirmed by the analysis, the phenomenon has observable adverse effects on the leader’s interaction with the team and decreases organizational performance within the team and disrupts healthy psychological climate. Simply put, the phenomenon is detrimental to organization’s productivity. Importantly, it is also preventable and thus needs to be addressed in order for the organization to retain its rate of performance and maintain a competitive advantage. The techniques identified in the study contain an observable potential to mitigate the said negative effects and thus are valuable for organizations.

Next Steps and Recommendations for Future Research