Introduction

One of the most non-obvious issues that is rarely discussed by public or academic critics is the need for pastoral care. While society is accustomed to providing quality care and maintaining an adequate level of supportive living for vulnerable members of society, this rarely extends to the clergy. The image of the pastor as a leader of church services is the central focus of this paper. The pastor, terminologically, is viewed in this essay exclusively as a person called to administer the sacraments and public sermons in Christian churches, and particularly Lutheran churches. At the same time, the work does not focus solely on Protestant currents of Christianity, which means that the conclusions drawn in the essay can be valid for Catholic and Orthodox older clergy members. Thus, the central thesis of this essay is that pastors, like other people, may experience psycho-emotional problems and thus need social support. The purpose of this paper is to discuss in detail the problem of stress and burnout among pastors and to identify ways to address the problem.

Support for Pastors

Pastors are one of the most vulnerable social groups, not because they are more prone to chronic illness or are associated with harmful work, but because of the stigma attached to them. The classical definition of stigma (not in a religious context, but in a sociological context) means the negative associations of an individual or group of individuals with something shameful and non-prestigious: thus, stigma has historically existed in relation to medieval women, dark-skinned slaves, and Jews. For pastors, of course, there is no publicly recognized stigma from believers since their work is associated with the fulfillment of a sacred duty. Metaphorically, however, there is still a stigma attached to such pastors: pastors are thought to have some divine authority and power that disqualifies them from the status of ordinary mortals. The classical pastor exemplifies sacredness and absolute sincerity, so it often seems that any problems of a domestic nature are absent from their attitudes. Vesting pastors with ecclesiastical ministries and privileges thus deprives them of public perception of their needs.

The emergence of such thoughts is not, on the whole, unwarranted or surprising. Pastors are often perceived by believing parishioners as having somewhat more power, wisdom, and privilege from the church. The letter to the Hebrews states that the high priest has the ability and power to condescend to ignorant and lost souls, as well as to offer sacrifices for sins (Heb 5:1-2). In this context, it is especially easy to draw a parallel between the high priest this passage describes and Jesus Christ. The Son of God gave his life as a sacrifice for the remission of universal sins, and the high priest, according to Hebrews, must be prepared to do the same. Such admonitions are not uncommon in biblical texts. The First Epistle to the Thessalonians admonishes Christians to unconditionally respect and care for their pastors as those who abide in the Lord (1 Thess 5:12-13). Hebrews 13 specifies that Christians are to follow their pastors as religious leaders (Heb 6:1-4). In addition, ministers are under constant pressure and strain for the heavy church duty that has become part of their lives-an an additional reason for unconditional respect for pastors (2 Cor 11:28). Finally, Acts summarizes that pastors are “…men… who are known to be full of the Spirit and wisdom” (Acts 6:1-4). All of this together becomes a reliable indication that pastors can be perceived as having some sacred power. Moreover, it is behind this perception that lies the major problem isolating pastors from everyday life.

The above passages from sacred Christian texts are not something abstract or distant from reality. On the contrary, the statistics perfectly support the idea that pastors tend to be perceived as having a different level and authority. For example, only about one in five pastors surveyed said they had no problem planning their personal lives, while four in five pastors could not find a balance between ministry and life outside of church (Barna 2017). In addition, Barna also reports that 70 percent of pastors have no friends, and in 27 percent of cases, they have no one to turn to for help in critical situations. Continuing on, 84 percent of pastors surveyed specified that they would like to have someone close for support, but for a variety of reasons, they cannot. Thus, the statistics showed clearly demonstrate a destructive trend: there are indeed some differences between pastors and the life of the unchurched individual, and perhaps this asceticism is the foundation for the “stigmatization” of pastors.

In reality, pastoral ministry always takes place on the integration of three perspectives. The first, and perhaps the most common, view the pastor as God’s chosen one (Akin and Pace, 2017). This paradigm makes sense because, unlike other members of society, only clergy members find themselves in the most excellent closeness to God-they have special vestments, and the rituals they perform seem exotic to everyday life. In this context, God chooses the pastor as one of his vicars in the world, and thus church authority (the power to decide church matters) is an extension of the divine will (Rom 13:1). However, this perspective seems entirely unfair: for reasons unknown, some people are chosen, and others are subordinated, which clearly contradicts theological principles of equality (Dennert 2021; Eph 5:21). This, in turn, is an additional pressure factor for pastors.

Another paradigm that considers the social role of the pastor is slavery through the will, as described by Martin Luther. It is recognized that the individual can comprehend God, and with it redemption and salvation, only through obedient service to him, which raises issues related to slavery. Being a Christian slave is not the same as historical slavery, but it still focuses on the unimpeachable authority of the Creator. Thus, when an individual decides to join a church (usually at a young age), he or she may be driven by a desire to comprehend God. Such a perspective recognizes an individual’s personal desire to become a Pastor and thus does not create social justice problems.

Finally, a third paradigm in the Lutheran Church, which answers the question of why people become pastors, is the theology of the cross. According to this perspective, faith in Christ is not limited to moments of success and glory but also through hardship and suffering. From this perspective, pastoring must be seen as a voluntary asceticism and deprivation of the goods of life, which is directed toward receiving the Great Blessing. Again, this Lutheran paradigm also creates no reason for social inequality, but along with an anthropological view, sees the pastor as an individual who is not different from other members of society.

The critical point here is that pastors, first and foremost, remain human beings who have all the traits and difficulties of the common individual. Even the Epistle to the Hebrews already mentioned states that a pastor is a man chosen from among men (Heb 5:1-2). It should not follow (though practice often shows the opposite effect) that pastors are endowed with some divine power or wisdom that others lack. The truth is that any clergyman has the same wisdom and powers as a believer familiar with sacred texts: the only difference is in the public roles performed. Whether the Christian is in the position of an office manager or near the church altar, in either case, he remains a member of society who may still face problems.

A preliminary definition of the public role of the pastor for church ministries has identified a problem faced by ministers in Christian churches around the world. Because of distorted perceptions of the pastor’s wisdom and authority, not enough resonance is created in society to recognize the need to care for them. Doubts may probably form in the minds of believers — “Why should we care for those of us who are closer to God if God is looking out for him?” — but it is clear that questions of this kind only feed an already persistent stigma. It is necessary to come to an understanding that a pastor, no matter how wise and capable he is, is always a lay person working in the church. This perception radically changes the plane of social vision and creates a space for discussion of the problems and solutions that the average pastor faces on a daily basis.

While a discussion of the specific reasons for the need for church counselors and pastoral assistance, in general, is the subject of the next chapter, by now, it is crucial to outline general ways to address the problem. Thus, an absolute recognition of the difficulties (or at least the likelihood of encountering them) is a predictor for creating solutions. One of the most effective strategies is to use the services of a church counselor to help pastors deal with crisis situations and not burn out professionally. Pastoral counseling is a modern tool in the hands of the church leader, which helps to manage the work environment and create a favorable climate in the religious organization. The use of such counseling allows one to view the classical church as a company and the clergy as ordinary employees: in this analogy, any doubts about the sanctity and ability of church officials to have personal problems seem inappropriate. Just as civilian company employees turn to an in-house counselor, coach, or mentor for help and advice, pastors can use the services of an internal counselor to address personal difficulties related to work and life outside the church.

In the context discussed, it is crucial to emphasize further that pastoral counseling is not the confessional and moral counseling provided to the laity by the clergy but the psychomental support that pastors themselves need. Providing social support, then, is a critical measure for providing needed assistance to a pastor who suffers from personal crises (Eagle et al. 2019). Such counselors help pastors cope with the heavy burden of their problems, which can especially be hidden due to societal stigma against clergy. This ranges from personal and family problems to difficulties of existential crisis and misguided career choices. Church counseling thus helps people with unique specializations cope with problems that make sense not only in the context of church leadership.

It makes sense to draw a parallel between the pastoral counselor and the psychologist. In a general context, there is no difference between the two professions, especially if one views the pastoral counselor as a full-time psychologist for the church. The task of the classical organizational psychologist is to use theoretical methods and principles to improve the overall corporate environment (Grand 2018). Improvement in this context can mean both increasing the company’s KPIs, be they profitability and sales, and supporting the mental well-being of employees. Since it is evident that measurements of business profitability are inappropriate with regard to the church, a religious, psychological counselor helps the “employees” of a church organization with their mental wellness. Notably, counseling does not necessarily take place in a church setting, although that is the most common place for a coaching session. In today’s world, the minister is free to use remote technology, such as Zoom, for remote sessions with a counselor.

Counseling with an in-house counselor is not the only proper strategy that all pastors should follow. As is often the case, even in churches where counselors are available, the quality and intensity of supportive therapy can have a disruptive effect. For this reason, pastors are often encouraged to see personal physicians who can examine their neurological condition from a body perspective. It is a known fact that many neurological conditions have symptomatic manifestations in the form of lingering apathy, depressive syndromes, and disorders (König 2019). As a consequence, the physician can provide physiological counseling and medication support, which would also make sense in addressing the pastor’s concerns. In the event that the physician does not identify any problems of a medical nature, this will be an additional benefit to the pastor as it will reduce health-related stressors.

The two strategies described above, staff counseling and physician consultation, are reactive methods that work with problems that have already happened. From a proactive perspective, it is appropriate to turn to preventive practice through a working culture. It is in the church leader’s power to create an organizational structure that will inhibit the manifestation of possible mental problems of pastors and other ministers. Borrowing from other companies allows for an environment where employees can share and support each other (Al Kerdawy 2019). In this corporate environment, employees tend to help each other and delegate tasks (Becker 2017). Examples of this include group activities, pieces of training, and joint celebrations that will establish the right atmosphere within the church. With this structure, ministers will be able to get the social support they need from their colleagues, which can be one component of a systemic solution to loneliness among pastors.

Reasons to Care

First and foremost, pastors are people who, like the rest of us, experience personal problems and crises in their lives. While it may seem from the outside that pastors are devoid of any worldly concerns because of their close connection to religious paraphernalia, this does not seem right. Fifty-seven percent of pastors say they are paid too little and cannot pay their bills, while 28 percent of pastors blame themselves for not being able to secure a proper family vacation (Barna 2017). These statistics show that pastors are just as many people with problems not qualitatively different from those of civil society.

Pastors, like everyone else, need help, but their lifestyles can prevent them from finding it. It is true that there is a specialist for every problem. When people’s house burns, they call the fire department, and when a crime occurs, they call the police. In this sense, any problems of a spiritual nature are usually dealt with by priests in the church. In turn, when priests encounter problems, they do not always have the freedom to choose whom to call. Although pastoral counseling, as shown in the last section, is a relevant and modern tool for dealing with pastoral mental difficulties, in practice, it is not always possible. For example, 66 percent of churches still lack psychological support for their ministers (Barna 2017). In this sense, one might recall the famous proverb “A shoemaker without shoes,” referring to the lack of help for pastors who are themselves called to provide spiritual help. In fact, this proverb goes back to the original texts of Luke, in which the evangelist wrote, “Physician, heal yourself!” (Lk 4:23). From what has been said, it can be concluded that the problem of lack of help for clergy is generally well-known and has a long history.

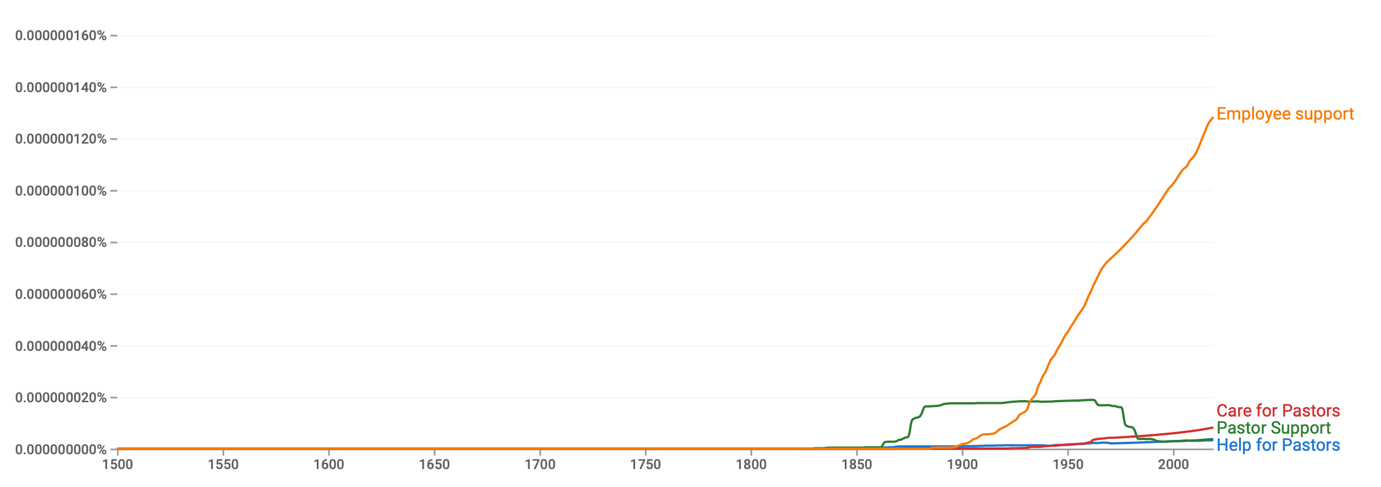

If one turns to the Figure below, one can see two not encouraging results. First, the frequency of occurrence of critical terms describing the need for support for pastors is critically low. Second, compared to the help given to the rank-and-file, the support of church ministers does not interest the print media with the same comprehensiveness. From what has been said, it is clear that ministers are forced to seek their own resources and opportunities for support because society is not always willing to give it to them.

From the perspective of one of Lutheranism’s Christological paradigms, God gives authority to people to be pastors, and it is this authority, from the perspective of the theological paradigm, that is a heavy burden for them. Pastors work daily with the appeals of parishioners, and themselves act as a source of endless support and help for Christians, which is entirely consistent with the functions that the Bible ascribes to pastors. Meanwhile, it is sinful laziness or negligence for clergy: while an office worker can skip some of the work or find tricks to make it easier, such opportunities are strictly forbidden in the case of a pastor. The New Testament mandates that pastors renounce laziness in favor of zealous service to God (Rom 12:11). This prescription is the foundation for the work of a responsible pastor-he is not allowed to be lazy, so he is compelled to work faithfully and fully. The laity comes in with various problems in the hope of receiving counsel from a holy father, and from the perspective of organizational psychology, this constant exposure can have a destructive effect on the pastor’s personality, leading to a condition called work stress.

Moreover, the pastor should be an example of godly ministry to all Christians because it is the pastor who is traditionally associated with God. Although any believer has the ability to reach out to God from home, transportation, or university, the church is still a stronghold of faith. According to Burke (2018), the main reason Americans continue to go to church is that parishioners want to grow closer to God. The functional role of the pastor, then, is to be a conduit between the Christian and God through the sacrament of service. This imposes very specific requirements on the pastor: he must be honest, sincere, and disciplined. The pastor seems forbidden to sin because he is perceived as one of the most sacred men. It is possible that because of such attitudes and expectations around the role of the pastor, many priests experience systematic stress.

Another significant factor that can contribute to stress is the lack of visible career advancement. In office life, an employee may work hard and perform well in order to get a promotion. With regard to church service, work is not measured by the same KPIs as it is for a civilian career. Indeed, there are opportunities to grow by the ministry in church organizations, but priests who have reached the top cannot take even higher ministries. Thus, the pastorate is doomed to be perpetual, which breeds routine.

The problem of pastoral professional stress is not a widely discussed public agenda, so only narrowly focused sources do research in this area. Meanwhile, the problem of such stress proves to be significant to the church community. According to Gaultiere (2018), 75 percent of pastors experience serious work-related stress, with only one in ten pastors not feeling tired and exhausted by the end of the work week. In addition, seven in ten pastors report experiencing depression syndromes. Consequently, the problem of stress is not an abstract issue for pastors but has a very measurable meaning. The condition of stress, however, is not unambiguous but instead is complex. In particular, work stress can be associated with a problem called burnout (Becker 2017). Pastoral burnout is a topic of academic research that should be highly popular but is not. For example, an analysis of the results on the exact Google Academy query reveals that the number of sources on burnout for nurses, for example, exceeds six thousand, but only 54 results for pastors. This further confirms the fact that research on pastors’ problems is not a current task of the current agenda.

Emotional burnout is a socially recognized problem. According to the original WHO interpretation, burnout should be understood as a syndrome resulting from chronic stress at work over a long period of time (WHO 2019). About 71 percent of pastors said they were burned out in the workplace (Frykholm 2018). At the same time, eight out of ten clergies cited severe effects of their church service on personal relationships, with one in three pastors reporting a church ban on starting their own family (Barna 2017). As a result of years of long service, pastors experience burnout, which leads to a number of psycho-emotional problems, whether it be apathy or a loss of energy.

The issue of support for ministers has recently become increasingly important. Responsible organizations and agencies, recognizing the full need for pastoral care, are opening their own foundations and support services that aim to provide counseling, coaching, and mentoring for clergy who find themselves in difficult situations. Such organizations help ministers not only in critical moments, whether grief, dismissal, or death, but also in cases where the individual is experiencing decadence. One example of such an organization would be Care For Pastors, a family firm that offers assistance to pastors (Care For Pastors 2021). Care For Pastors’ mission is to support pastoral families in ministry through practical assistance and communication. The emergence of such organizations is a solid indication that this issue is gaining prominence on the public agenda.

Outcomes

When the significance of the problem of occupational stress and burnout is no longer in doubt, and when possible solutions to the problem have been discussed, it is essential to explore the possible outcomes to which a stressed pastor might arrive. In this sense, it is paramount to discuss possible adverse outcomes in the event that no help is forthcoming. One of the most destructive measures is suicide: newspaper sources often report chronic suicide cases committed by pastors (Andersen 2019). It is notable that many of their victims had families, jobs and served the community, but at one point, they decided to take their own lives. Andersen raises the concern that there are no official statistics on suicide among pastors; furthermore, there is no data showing the intensity of activist work with priests to prevent suicidal thoughts. Critically, it is essential to recall the fact that suicide is not respected by the Christian religion. Sacred texts describe suicide as an act of low self-awareness, revenge, or fear (Judg 9:52-54; Judg 16:25-30). Suicide is a violation of the divine will and is contrary to the fifth confession (Exod 20:13). Consequently, a pastor who knew the laws of the sacred world better than anyone else and decided to commit suicide certainly had good reasons for this difficult decision.

A less painful outcome of a stressed pastor can be to leave the church voluntarily. This is really one of the effective methods: when church service causes problems and difficulties, even though it originally had other goals, a pastor can end it and retire. Leaving the church, in general, is one of the most common practices among pastors. Feeling lonely and isolated from the community, one in two ministers consider leaving the service (Maxwell 2019). Lack of support from church leadership often leaves pastors no option but to leave the church and either retire or take a civilian position.

However, if support is given to pastors under stress, the outcome can be a better religious experience. A person who has voluntarily chosen to serve God in the church may have pure intentions and motivation but face challenges in his or her theological journey. Having support in such situations has been shown to be a very important component of successful ministry. When a pastor experiences doubt, apathy, or stress, he or she can seek help from either church counselors or outside organizations to get advice and restore disturbed psycho-emotional balance. Such a pastor may continue to serve God if he feels that his problem has been resolved or he has learned to cope with it. It is also possible that a pastor will voluntarily leave the church after counseling if he feels that it was serving God that brought him the difficulties he had. In either case, with counseling, the outcome is most favorable because it preserves the mental health of the individual.

Indeed, the benefits of counseling are also noticeable for the church. Every time a pastor leaves a church organization, it becomes a problem for its leadership, tantamount to a leader leaving a for-profit organization. Investing in the creation of in-house counseling is a preventive measure that allows the church to maintain its structure and a favorable atmosphere within the church community. In addition, from an organizational standpoint, the church receives an improved reputation for its members and new theological professionals, which enables the church to fulfill its functions more competently and effectively.

Conclusion

To summarize, at the outset, the issue of psychological support for pastors is important and relevant, although it does not have as much public recognition. It is worth noting that pastors are not sacred people and certainly are not closer to God than any other believer. However, there is a very measurable stigma about them that seems to keep priests from having mental problems. The fulfillment of their functional role, expectations from parishioners, and lack of adequate leadership in church organizations become causes of professional stress and burnout in pastors. The paper has shown that the solution to this problem lies in providing social support from professional counselors, psychologists, and coaches who are supportive, listening, and encouraging. This measure does not seem all that complicated, but it is one that is so critically needed in today’s church to preserve its reputation and maintain the mental health of its staff.

Reference List

Akin, Daniel L., and R. Scott Pace. 2017. Pastoral Theology: Theological Foundations for Who a Pastor is and What He Does. Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group.

Al Kerdawy, Mostafa Mohamed Ahmed. 2019. “The Role of Corporate Support for Employee Volunteering in Strengthening the Impact of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Corporate Social Responsibility in the Egyptian Firms.” European Management Review 16 (4): 1079-1095.

Andersen, Ericka. 2019. “Why Do Pastors Die by Suicide?” ERLC. Web.

Barna, George. 2017. “Statistics in the Ministry.” Pastoral Care Inc. Web.

Becker, Jody. 2017. “The Ecological Gift of Spiritual Formation: A Renewal for Healthy Clergy.” George Fox University. Web.

Burke, Daniel. 2018. “10 Reasons Americans Go to Church –– And 9 Reasons They Don’t.” Web.

Care For Pastors. 2021. Our Vision & Mission (website). Web.

Dennert, Brian. 2021. “Chosen By God – The Biblical Basis For Election.” Faith Church. Web.

Eagle, David E., Celia F. Hybels, and Rae Jean Proeschold-Bell. 2019. “Perceived social support, received social support, and depression among clergy.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 36 (7): 2055-2073.

Frykholm, Amy. “Your Pastor Isn’t as Unhealthy as You Might Think.” Christian Century. Web.

Gaultiere, Bill. 2018. “All Articles Pastor Stress Statistics.” The Aquila Report. Web.

Grand, James A., Steven G. Rogelberg, Tammy D. Allen, Ronald S. Landis, Douglas H. Reynolds, John C. Scott, Scott Tonidandel, and Donald M. Truxillo. 2018. “A Systems-Based Approach to Fostering Robust Science in Industrial-Organizational Psychology.” Industrial and Organizational Psychology 11 (1): 4-42.

König, Alexandra, Nicklas Linz, Radia Zeghari, Xenia Klinge, Johannes Tröger, Jan Alexandersson, and Philippe Robert. 2019. “Detecting Apathy in Older Adults with Cognitive Disorders Using Automatic Speech Analysis.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease 69 (4): 1183-1193.

Maxwell, Julie. 2019. “Why Pastors Leave the Ministry.” Shepherds Watchmen. Web.

WHO. 2019. “Burn-out an “Occupational Phenomenon”: International Classification of Diseases.” WHO. Web.