Statement of Problem/Purpose of Paper

Family therapy is a subset of counseling that focuses on familial relationships between family members, couples, and parents and children. In contrast to individual treatment, it is based on using the relations inside families to address the issues with which they may be concerned. One type of potential client is families impacted by an intellectual disability (ID) – a parent, relative, or child may have an ID that influences the family unit’s dynamic or leads to changes in their daily lives.

Intellectual disability refers to the limitations in adaptive behavior and intellectual functioning that a person starts experiencing before turning 18 (McGuire et al., 2019). Such issues may include slow or disrupted development of social skills and communication patterns and difficulty completing basic living tasks (McGuire et al., 2019; Totsika et al., 2020). Many people with ID experience mild or moderate symptoms, and the range of cognitive and adaptive skills’ attribution differs from one person to another. Nevertheless, this diagnosis often becomes a source of strain in the family due to parental anxiety or other environmental factors (Crossno, 2011; Lara & de los Pinos, 2017). Therefore, it is vital to consider the ways of conducting psychotherapy for families impacted by ID.

The number of children with ID continues to grow in the United States and globally. In 2016, the prevalence of children with ID between the ages 3 and 17 years was more than 11% (McGuire et al., 2019, p. 444). Older children and boys were found to have ID more often than other groups, and the survey noted a trend of a significant increase for this particular disability (McGuire et al., 2019). Such a high prevalence of ID implies that many families have a child or a relative who lives with ID and may require additional support or help with performing academically or completing basic daily tasks (Lara & de los Pinos, 2017). Apart from that, people with ID can be a source of conflict in a family due to the other members’ perspectives on disabilities (Crossno, 2011; Lara & de los Pinos, 2017; McDonnell et al., 2019). Thus, discussing therapy for families impacted by ID is a necessary part of developing psychotherapeutic approaches.

People with ID experience hardships both due to the systems unprepared to meet their needs and interpersonal conflicts. For instance, children with ID are two to three times more likely to experience maltreatment and all forms of abuse in their household (McDonnell et al., 2019). Young people with ID often encounter family neglect and victimization, which further affects their ability to maintain a fulfilling lifestyle (McDonnell et al., 2019). However, even in families that do not have abuse, children with ID can become both sources and recipients of increased anxiety due to their disability-related needs and behaviors. In this case, psychotherapy can act as one of the solutions to balance family connections.

As adults, ID can become a factor in increasing partner violence. Individuals with ID are at a higher risk of entering and staying in relationships in which their experience physical, emotional, and sexual abuse than adults without ID (Bowen & Swift, 2019). Depending on their level of disability, parents with ID also experience problems in a family and their relationships with children, additionally to other external issues (Coren et al., 2018). Mothers with ID are at increased risk of single parenthood, poor mental health, and low socioeconomic condition (Coren et al., 2018). In turn, children of parents with ID can experience higher rates of neglect and subsequent health problems (Coren et al., 2018). All family dynamics are in some way impacted by ID, raising the question of whether and how psychotherapy can assist people in addressing these problems.

Psychotherapy for families aims to address such conflicts and help people to understand themselves and their relationships within the unit. Several theories and approaches are used to explain the cause of issues and attempt to solve them. This paper aims to review one strategy grounded in theory (Bowen’s family systems theory) and one practical program based on active engagement and learning (Behavioral Parent Training, BPT). The paper intends to analyze the existing literature on these two approaches, critique them based on their potential application in this particular scenario, and discuss future research in therapy for families with ID.

Review of the Literature

Bowen’s Family Systems Theory

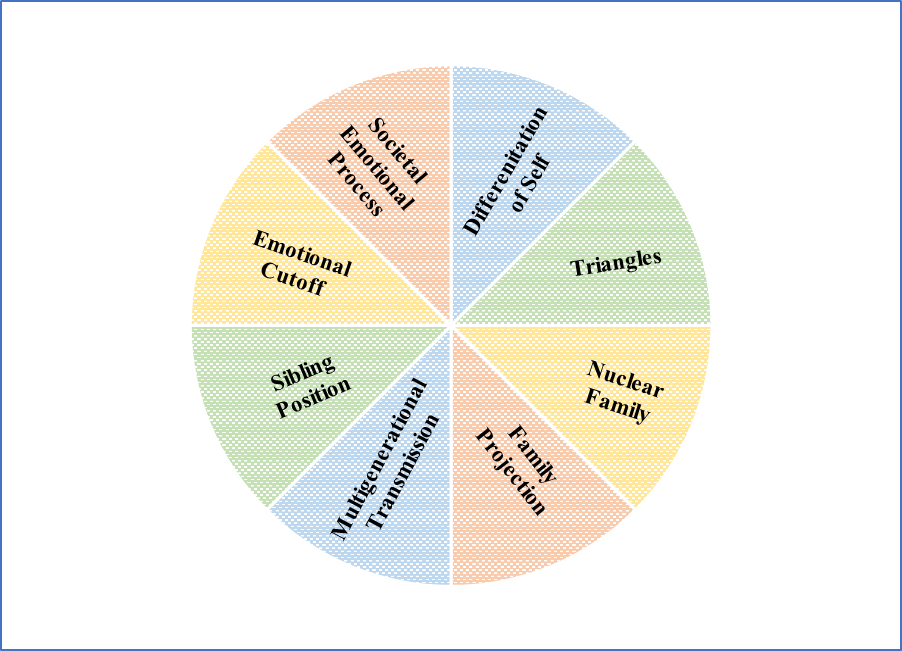

The family systems theory is an approach that heavily relies on a theoretical rather than practical basis. At the core, it is a view of the family as a system with subsystems that continuously change and interact. Such systemic thinking guides the practitioner in introducing the theory to their practice, and it becomes the main framework for all client sessions (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019). Bowen introduced eight concepts of the family systems theory – each of them cannot be viewed in separation as they all play a role in the family dynamic, as shown in Figure 1.

The first concept, Differentiation of Self, refers to the necessity of a person defining themselves in a family. While absolute differentiation is not possible, highly differentiated people can think through crises rather than rely on their emotions (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019). Differentiation allows one to have coping mechanisms and principled personal beliefs that do not waver under other people’s influence (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019). The second concept is one of the most important – Bowen states that twosomes, relationships between two people, are highly unstable and always attract a third person to maintain balance. Triangles develop in any setting as the most stable form, in which the connections between members continuously change (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019).

Family members respond to change and adapt or absorb any emotional responses that the other individual expresses (Kerr, 2019). Children, in particular, become the target of projection, through which parents direct their negative perceptions towards a child. Bowen further discusses the projection across generations as children grow up and create their own families (Kerr, 2019). Another concept is that sibling positions impact family relationships both for siblings themselves and their future potential romantic relationships. As siblings develop specific roles in a family, they may prefer a partner with complimenting characteristics (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019). Finally, Bowen suggests that a family system’s influence extends outside of personal relationships inside a family into the outside world, affecting society (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019).

These concepts are used in therapy as a guideline for helping clients reach within themselves and understand their family problems from the perspective of family roles and connections. Bowen’ theory implores therapists to act as a distanced observer who establishes rapport but does not interfere with the relationship triangle. Moreover, psychotherapy based on this theory deters specialists from giving specific advice, allowing families to listen to one another and come up with their own solutions. The intervention targets the most motivated person in the family and encourages all participants to voice their “I positions” (Crossno, 2011; Kerr, 2019). The therapist provides teaching about emotional systems and gives family members a framework through which they solve their problems at home.

Application in Families Impacted by ID

Bowen’s family systems theory is considered in a variety of settings. However, it is often used in scenarios where the balance in family relations has been recently disturbed, or the anxiety has reached a high level (Crossno, 2011). In families where one member has an ID, other members may turn to therapy with a specific goal of changing or “fixing” this individual (Crossno, 2011; Haefner, 2014; Hill‐Weld, 2011; Kerr, 2019). However, family systems therapy offers a different approach, where each person works only on changing themselves and not interfering with others’ behavior, as the theory focuses on the reciprocity inside a family (Crossno, 2011; Haefner, 2014).

As an outcome, it has been found that family system therapy helps to depathologize the ID and move the focus away from the disability towards family dynamics (Fidell, 2000; Haefner, 2014; Hill-Weld, 2011). Instead of treating individual symptoms, the therapy suggests each willing family member consider their own beliefs and actions and see how they impact the relationship with other people (Carr, 2019; Kerr, 2019). It is notable that most cases of this theory implementation focus on parents as responsible for changing the family dynamic, regardless of who has an ID among the family members (Haefner, 2014; Hill-Weld, 2011). The essential concepts of Bowen’s teachings place parents in a leadership position, potentially explaining this finding.

Behavioral Parent Training

In contrast to theory-focused family systems theory, behavioral parent training (BPT) is a skills-based intervention. It is mostly known as an approach to helping families where children have attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Carr, 2019). However, it has been researched in family members with ID. In this approach, the main idea is to provide parents with skills to respond to children’s non-compliant, aggressive, or otherwise disruptive behaviors (Feldman & Werner, 2002). In particular, parents learn about techniques to reinforce positive and desirable behaviors and to discourage unwanted behaviors. Communicative skills are also a part of education, as they assist in strengthening parent-child interactions (Crnic et al., 2017; Feldman & Werner, 2002). Therefore, this particular intervention is a form of therapy that dictates specific ways of behaving for parents and gives them tools to observe and respond to their child’s behavior.

Application in Families Impacted by ID

Similar to the application of Bowen’s family systems theory, BPT has been researched for families where parents or children have ID. In cases where children have an ID, parents are taught to respond to actions as well as monitor their own stress levels (Crnic et al., 2017; Weeland et al., 2021). After completing a BPT course, parents report fewer problems related to child behavior, a better quality of family life, and fewer disruptions based on child actions (Crnic et al., 2017; Feldman & Werner, 2002). They also feel less stressed when dealing with problem behavior and more confident in their abilities as parents (Crnic et al., 2017; Feldman & Werner, 2002). Specific BPT programs for ID have been developed to address the needs of children with ID, as their behavior differs from those with ADHD (Crnic et al., 2017; Feldman & Werner, 2002). Consistent with the systems theory, it is found that parents’ behavior mediates the children’s actions (Crnic et al., 2017; Feldman & Werner, 2002). Thus, research suggests that BPT is effective for helping family relations and parents’ preparedness to raise children with ID.

Another type of BPT program is the one that deals with parents with ID raising children with or without ID. A review of such interventions performed by Coren et al. (2018) found a number of studies that aim at teaching parents with ID the necessary social skills and safe parenting techniques to improve their family interactions. While the evidence quality is low, the findings suggest that BPT can be effective for parents with ID. It creates better and safer home practices, helps parents recognize their children’s health needs, and decreases parenting-related stress (Coren et al., 2018). BPT seems to be an effective practical intervention that helps families where parents and children can have ID, but more evidence is needed to review different family dynamics.

Discussion and Implications

Critique of Bowen’s Family Systems Theory

From the evidence about the implementation of systems theory in psychotherapy of families impacted by ID, it becomes apparent that this approach can improve family relations. Bowen’s strategy challenges the idea that one particular person is at fault in a family conflict or that there exists a “fix” for ID. Thus, it helps destigmatize disabilities, shifting the focus on interpersonal connections and all family members’ internal change. This is a strength of the approach that is supported by the evidence discussed above. Another potential advantage of the theory is that it does not give clear instructions, keeping the authority in clients’ hands instead. During such sessions, the therapist does not include a personal view of the problem, rather acting as a communication channel between family members (if they are attending together). If a client is visiting the specialist alone, there still exists a chance to give them tools for self-reflection that will lead to better relationships in the family.

Simultaneously, family systems theory has limitations that weaken its potential effect. First, as the approach is theoretical, it requires the client to do a lot of thinking without structured guidance. They also do not have any “homework” that would tell them how to act or what to do to work on their relationships. Upon leaving the therapist’s office, a client may not have any solid instructions on what they should choose the next time they face a conflict situation. The theory encourages them to come up with their own solutions. Therefore, a specialist has limited power over the family’s change, and the client does not have clear guidelines they should follow. This is a disadvantage, especially if clients expect to be guided rather than given basic tools. However, it can also positively influence clients who are disobedient or do not enjoy practical exercises.

The main weakness of therapy based on the systems theory is that it is effective with clients who are willing to put significant time and effort into changing their situation. As noted above, many parents of children with ID expect therapy to “fix” their child and remove unwanted behaviors. In these scenarios, parents are unlikely to see their actions as a potential factor in their parent-child relationships and their children’s undesired behavior. As a result, if a client does not actively engage in thinking about how family systems in their particular case interact, the family may not see a major change.

Critique of Behavioral Parent Training

BPT programs are advantageous in cases where parents want to have clear guidelines on how they can improve their family relationships and the behavior of their children. In contrast to the systems theory, this approach is direct and practical – it explains to parents which skills may be necessary to acquire. Thus, parents leave the office with directions and knowledge that they can use in crisis situations and any interaction with their child. At the same time, BPT is similar to Bowen’s theory in that it does not focus on the effect of ID on the family but places much responsibility on parents. In cases where a child has an ID, parents are shown that their behavior is a vital factor in successful parent-child interaction. If a parent has an ID, then such training is used to work with potential limitations to increase children’s safety without trying to undermine the parent’s disability.

Nevertheless, by offering practical solutions and providing parents with instructions, BPT potentially limits the parent’s ability for self-reflection. As an intervention, training does not focus on the parents’ thoughts and feelings about their family issues, as well as their other relations (for example, with their parents). While it may not be necessary in all cases, the tools offered by a theoretical approach have the potential of influencing their thinking on a deeper level. Moreover, as parenting skills offered in BPT are likely to be standard rather than individualized, parents may feel frustrated if their new skills do not work in their particular case. Here, a comparison with Bowen’s theory can be shown – the theoretical approach leaves the clients in charge of creating solutions. Thus, it is highly flexible and adaptable to any case. BPT may not offer the same freedom, leaving parents who did not engage in introspection dissatisfied with therapy.

Conclusion

Psychotherapy for families with ID can deemphasize one’s disability as the main factor in family conflict. Both approaches reviewed in this paper – Bowen’s family systems theory and BPT shift the attention away from disability towards family members’ behaviors and their interconnectedness. Bowen’s theory places significant responsibility on parents, but it also applies a systemic view of all connections and actions inside and outside the family unit. Its goal is to give clients tools to interpret their situation, encouraging them to develop a personal solution. BPT, in contrast, poses that parent’s preparedness to raise children directly affects the family’s relationship and children’s behavior. While having many similarities, the two types of therapy are different in their strategy.

As the research of the approaches shows, there exists some evidence of their effectiveness. Nevertheless, future research should be conducted in order to support the findings and test other scenarios. For the family systems theory, more studies are needed to appraise the long-term effect of therapy on families with ID. In the case of BPT, much of the current evidence has low quality, and it does not demonstrate how exactly BPT influences family relationships. Another consideration for future investigation is whether it is possible to combine the two approaches, uniting their strengths and mitigating their weaknesses.

References

Bowen, E., & Swift, C. (2019). The prevalence and correlates of partner violence used and experienced by adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and call to action. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 20(5), 693-705. Web.

Carr, A. (2019). Family therapy and systemic interventions for child‐focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 153-213. Web.

Coren, E., Ramsbotham, K., & Gschwandtner, M. (2018). Parent training interventions for parents with intellectual disability. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, (7), 1-47. Web.

Crnic, K. A., Neece, C. L., McIntyre, L. L., Blacher, J., & Baker, B. L. (2017). Intellectual disability and developmental risk: Promoting intervention to improve child and family well‐being. Child Development, 88(2), 436-445. Web.

Crossno, M. A. (2011). Theories in marriage and family therapy: Bowen family systems theory. In L. Metcalf (Ed.), Marriage and family therapy: A practice-oriented approach (p. 39-64). Springer.

Feldman, M. A., & Werner, S. E. (2002). Collateral effects of behavioral parent training on families of children with developmental disabilities and behavior disorders. Behavioral Interventions: Theory & Practice in Residential & Community‐Based Clinical Programs, 17(2), 75-83. Web.

Fidell, B. (2000). Exploring the use of family therapy with adults with a learning disability. Journal of Family Therapy, 22(3), 308-323. Web.

Haefner, J. (2014). An application of Bowen family systems theory. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(11), 835-841. Web.

Hill‐Weld, J. (2011). Psychotherapy with families impacted by intellectual disability, throughout the lifespan. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities,5(5), 26-33. Web.

Kerr, M. E. (2019). Bowen theory’s secrets: Revealing the hidden life of families. WW Norton & Company.

Lara, E. B., & de los Pinos, C. C. (2017). Families with a disabled member: Impact and family education. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 237, 418-425. Web.

McDonnell, C. G., Boan, A. D., Bradley, C. C., Seay, K. D., Charles, J. M., & Carpenter, L. A. (2019). Child maltreatment in autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disability: Results from a population‐based sample. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(5), 576-584. Web.

McGuire, D. O., Tian, L. H., Yeargin-Allsopp, M., Dowling, N. F., & Christensen, D. L. (2019). Prevalence of cerebral palsy, intellectual disability, hearing loss, and blindness, National Health Interview Survey, 2009–2016. Disability and Health Journal, 12(3), 443-451. Web.

Totsika, V., Hastings, R. P., Emerson, E., & Hatton, C. (2020). Early years parenting mediates early adversity effects on problem behaviors in intellectual disability. Child Development, 91(3), e649-e664. Web.

Weeland, J., Helmerhorst, K. O., & Lucassen, N. (2021). Understanding differential effectiveness of behavioral parent training from a family systems perspective: Families are greater than “some of their parts”. Journal of Family Theory & Review. Web.