Introduction

Bandura’s social cognitive theory (SCT) is among the interpersonal models that find multiple applications in healthcare and behavior change interventions to promote patients’ well-being. The theory was proposed by Bandura to display the links between human behaviors and their determinants, including a person’s environment, personal-level factors, and cognitive or behavioral factors. This paper will use the mapping approach to discuss the theory’s internal structure and detail its application to health education for a smoking patients.

Main body

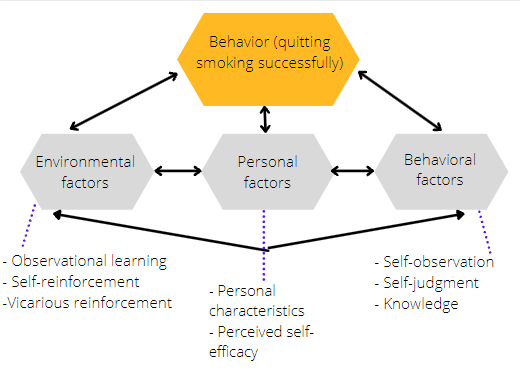

J. is a 26-year-old American who has been smoking cigarettes for the past four years and has a history of chronic cough and gingivitis. Working in a stressful environment, he started smoking as a way to relax and gradually developed the pernicious habit, resulting in the tendency to smoke 3-4 cigarettes a day. As figure 1 demonstrates, SCT describes the determinants of behavior, so this theory could inform effective health education to reduce and gradually eliminate nicotine use in the described hypothetical case. By analogy with SCT-based behavior change interventions focusing on type II diabetes and obesity, the patient should be provided with the knowledge to increase his self-efficacy and self-regulation (Bagherniya et al., 2018; Ghoreishi et al., 2019). Aside from promoting beliefs about a full-fledged life without tobacco products, the theory calls for the application of modeling or observational learning to expose the client to reference models (Ghoreishi et al., 2019). Possible examples of this are other patients’ smoking cessation cases. Education based on the mentioned theory could alter the client’s perceptions of his habit’s power over him, resulting in improvement-promoting changes to the man’s thinking.

The health education program for J. based on SCT should emphasize relevant environmental factors by promoting both self-reinforcement and modeling in smoking cessation activities. As for self-reinforcement, one of the methods of self-conditioning, the patient might be advised to implement the consequences approach in an appropriate form. Possible strategies might include spending a certain amount of money on charity for increasing nicotine consumption during the first stage of cessation or experiencing smoking relapses during nicotine replacement therapy. The elements of vicarious reinforcement could be incorporated in patient education by using national statistics and real but anonymized patient cases. This would enable the educator to demonstrate the effects of long-term smoking, such as lung disease, heart disease, and cancers affecting the mouth, the lungs, and the throat. Next, as for modeling or observational learning, the educator would provide the client with information on offline or online support groups for those quitting smoking (Al Onezi et al., 2018). J. would be able to engage in the exchange of experiences with peers who refrain from smoking tobacco successfully. These efforts would make his social surroundings aligned with the expected behavioral outcome.

To continue, the personal factors that SCT emphasizes would be considered to provide effective education. Bandura’s theory posits that observational learning occurs when a person is motivated to explore and produce the behaviors being modeled (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020). This motivation is predicted by several factors, including “the perceived similarity to the model” (Schunk & DiBenedetto, 2020, p. 4). It would be beneficial to use reference models (successful smoking cessation cases) and sources of vicarious learning (cases of smoking-related disease) that would be close to J. both culturally and demographically.

The need for relevant sources of observational learning can be justified scientifically. For instance, drug abuse research indicates that women’s smoking relapses are linked with psychological stress, whereas in men, cigarette craving is more intense in response to environmental reasons (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2020). Moreover, cultural factors, such as the normalization of smoking by society, can affect smoking cessation behaviors (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2020). These findings suggest that quit-smoking advice received from male peers raised in J.’s native culture would promote optimal coping strategies in the patient’s case. With that in mind, apart from selecting relevant disease cases for demonstration, the educator would encourage J. to develop and maintain contacts with male peers who have already achieved his desired goal.

SCT singles out behavioral factors that influence health choices, and they would inform the skills training part of the health education program to improve J.’s health outcomes. Among these factors are health-related knowledge and self-regulation skills enabling a person to choose the best possible course of action and remain cognizant of one’s issues and reactions (Bagherniya et al., 2018). In J.’s case, to achieve knowledge improvement, the educator could apply andragogy principles to explain the physiological and psychological mechanisms of nicotine addiction in plain terms. If retained properly, this knowledge would support the client in rationalizing his sudden desire to smoke and understanding social situations in which craving intensifies. Finally, an improved understanding of the psychology of addition would promote the client’s ability to engage in self-observation and keep track of thoughts and circumstances that increase or decrease the likelihood of smoking relapses.

Summary

To sum up, in the context of smoking cessation, the main propositions of SCT could be used to alter personal, environmental, and behavioral factors in a way that is conducive to adopting healthier behaviors. Specifically, SCT demonstrates the effectiveness of observational learning and can inform interventions to maximize the influence of positive or negative role models on health-related choices. Positive changes to behaviors also require new knowledge and improvements peculiar to self-observation abilities.

References

Al Onezi, H., Khalifa, M., El-Metwally, A., & Househ, M. (2018). The impact of social media-based support groups on smoking relapse prevention in Saudi Arabia. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 159, 135-143. Web.

Bagherniya, M., Taghipour, A., Sharma, M., Sahebkar, A., Contento, I. R., Keshavarz, S. A., Darani, F. M., & Safarian, M. (2018). Obesity intervention programs among adolescents using social cognitive theory: A systematic literature review. Health Education Research, 33(1), 26-39. Web.

Ghoreishi, M. S., Vahedian-Shahroodi, M., Jafari, A., & Tehranid, H. (2019). Self-care behaviors in patients with type 2 diabetes: Education intervention base on social cognitive theory. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews, 13(3), 2049-2056. Web.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2020). Tobacco, nicotine, and e-cigarettes research report: Are there gender differences in tobacco smoking? Web.

Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 1-47. Web.