When coping with a psychiatric condition or trauma, it is not uncommon for individuals to seek assistance. When dealing with trauma and its long-term consequences, friends and professional therapists may be invaluable resources. People from many walks of life are touched by a traumatized victim’s tale (Marsac & Ragsdale, 2020). Trauma to caregivers frequently has behavioral consequences that children unintentionally encounter. If a parent has Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), the child may ultimately suffer mental anguish, even if the youngster did not see the traumatic incident directly (Kellogg et al., 2018). When someone learns about the personal trauma experiences of another, they are put under emotional pressure, which is known as secondary traumatic stress. The trauma of maltreatment, violence, environmental catastrophes, and other unpleasant experiences affects over ten million American children every year (Secondary traumatic stress, N.D.B). Behavioral and emotional issues resulting from these events may have long-term effects on children’s lives, putting them in touch with child-serving professionals.

Review of literature

Trauma responses or PTSD may be “passed on” to children in two ways. For example, secondary trauma may be passed down through the generations in perhaps the most technical sense-via one’s D.N.A. Although the idea is still in its infancy, a recent study has shown that PTSD may be handed down from one generation to another (Smoller, 2016). For the most part, children who experience firsthand circumstances have close acquaintances or distant relatives. There is a lot of touch and interaction between them, and this affects their mental health. Such exposures may result in PTSD. Traumatic childhood experiences and early life stressors are associated with increased behavioral and health issues in children (Akinsulure‐Smith et al., 2018). Also, the authors added that traumatic stress contact has often had a link to emotional fatigue, depersonalization, eating disorders, sleep disruption, and decreased self-esteem due to burnout (Akinsulure-Smith et al., 2018).

It is critical to screen and evaluate children because it gives parents the chance to intervene and alter the course of their child’s life. Listening to the tales of traumatized children may be emotionally draining for psychiatrists, child welfare professionals, caseworkers, and other professional experts who deal with traumatized youngsters (Menschner & Maul, 2016). Protecting workers’ health and guaranteeing that children get the best medical service from those dedicated to assisting them begins with raising awareness regarding the consequences of indirect victimization among supervisors and employees alike.

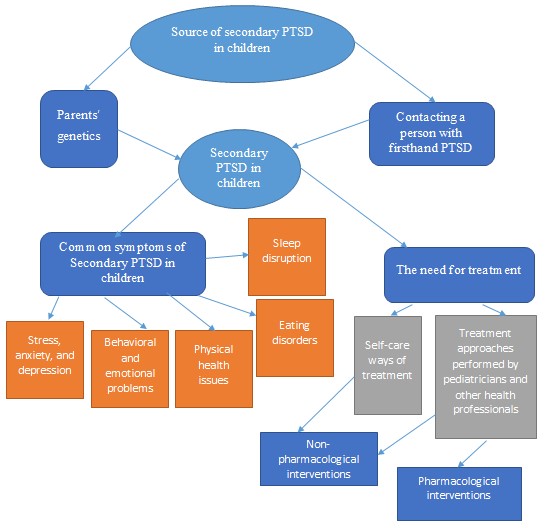

It is important to examine secondary PTSD in children to discover an effective method to protect children’s mental welfare and subsequent generations in the United States and abroad. It is crucial to examine the children of veterans who have PTSD (Katz, 2019). Additionally, the study analyzes ten different pieces of literature to enhance the understanding of the complex topic. Specifically, incorporating the facts from all the sources can help identify the specific factors exposing children to secondary PTSD and the negative consequences associated with the condition. Thus, this short discourse takes advantage of a mixed methodology to understand the complexity of this issue. The presented facts offer a foundation for future studies seeking to create community members—[See figure 1 that illustrates the conceptual framework].

The Definition and Significance of the Study

Understanding child PTSD is a fundamental element in determining or predicting the future tendencies and outcomes of future life in terms of health, behavior, and social well-being. Knowledge of this topic will help identify children undergoing traumatic experiences in society, either at home or school (Sachser et al., 2018). This will aid in the early diagnosis and treatment of the victims (Rezayat et al., 2020). It has also been proven that this information will contribute towards the apprehension of child offenders, a crime sector that has been on the rise across many areas in the United States (Cloitre et al., 2021). Most of the children who have PTSD are usually misunderstood, with a majority of them being tagged as rude, “different,” or anti-social (Cloitre et al., 2021).

This study aims at providing sufficient data that, in conjunction with the already existing information, will help formulate and, after that, ensure that the correct and prompt diagnosis is made. This study will advise on the appropriate treatment accorded as it has been noted that PTSD is misdiagnosed and treated as depression in most cases (Rezayat et al., 2020). Finally, the study will create awareness among public and medical practitioners as to what PTSD is, the causes and effects in children (Sachser et al., 2018). The relationship between parents’ experiences and interactions with the onset of PTSD in children will be explored.

The Quality of Existing Literature and Research on PTSD

Research has been conducted targeting various areas of interest in children’s mental health. Children’s primary mental health components include social well-being and psychological and emotional wellness (Grant et al., 2020). PTSD in children received less attention over the past few decades, because many believe that youngsters and adolescents are not stressed because they are cared for by parents (Garza & Jovanovic, 2017). This angle of view is not entirely proper, owing to the research and publications reviewed in this article. There is vast information on the management of treatment and prevention of PTSD in children (Hamblen & Barnett, 2018). Many law offenders in the United States have been found to have been victims of traumatic experiences in their childhood (Sherman et al., 2016). This discovery goes a long way in demonstrating the prognosis of the young victims of PTSD.

PTSD has just recently been recognized as a viable diagnosis in America. This late consideration is responsible for the scant research done on this topic. A lot more data is needed to ensure a better understanding of the aspects of post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents. This deficiency in information calls for an advanced study of this topic to provide enough information to supplement the existing data (Yue et al., 2020). The information will also inform the government policy, medical practice, and child support in providing better child care services (Van Ee et al., 2016). Therefore, there is an apparent need to conduct more detailed research soon concerning the areas that have not been adequately covered.

Study Gap in Literature Review

As determined in the review of existing scholarly literature, certain areas of PTSD in children have not been covered. This study aims to cover those areas to provide an adequate awareness of the condition. The following aspect will be explored upon the successful completion of this study:

- The causes of traumatic stress in children.

- The effects of post-traumatic stress disorder in children.

- The involvement and awareness of children’s PTSD.

Research Questions

What Causes Secondary Traumatic Stress in Children?

To delve more into this topic, it is essential to understand what exactly causes secondary childhood trauma. According to medical specialists, parental genes and contact with someone who has firsthand PTSD are critical contributors to the disorder. Trauma survivors might pass on secondary stress disorder to their children and grandchildren (Marsac & Ragsdale, 2020). In addition, talking to or listening to a disturbed person might harm the listener’s psychological health and perhaps set off the illness (Malarbi et al., 2017).

Due to proximity, it is not uncommon for children to be exposed to their parents’ distress. Children who hear their parents discussing, mentally reliving, or demonstrating signs of PTSD after experiencing trauma may begin to exhibit trauma responses of their own (Secondary traumatic stress, N.D.A.). Numerous triggers cause the rush of memories, including sounds, images, smells, and in some cases, nothing at all. These traumatic events are frequently accompanied by strong emotions such as fear, sorrow, and rage, and they might feel so vivid that the person with PTSD believes the incident is repeating itself (Malarbi et al., 2017). Even if it is difficult for a caregiver to go through the trauma repeatedly, the young ones who witness it can be worried and confused.

How does Secondary PTSD Affect a Child?

The other question relates to how secondary PTSD affects children and how a medical practitioner can determine if a patient has PTSD. The symptoms of vicarious trauma can range in severity from mild to severe. Some of the less severe symptoms include insomnia and food issues such as bulimia nervosa and anorexia nervosa. On the other hand, stress, worry, and negative behavioral and emotional alterations are severe indicators and symptoms (Smoller, 2016).

Anxiety and physical ailments, such as tiredness and a weaker immune system, can result from secondary PTSD in youngsters. When the first symptoms of a mental illness are noticed, parents should immediately take their children to see a mental health professional (Secondary trauma affects teens and young adults, 2020). Secondary PTSD necessitates treatment like any other illness or condition. This condition can be prevented and treated with the support of psychotherapists (Meiser‐Stedman et al., 2017). Compassion fatigue prevention and treatment strategies fall into two categories: non-pharmacological and pharmacological. Non-pharmacological approaches include seeing a psychologist, using self-validation and insight meditation, engaging in regular physical activity, daily scheduling, and keeping a sleep routine and journal (Menschner & Maul, 2016). Recurrent stress disorder can be prevented or treated with medication. Pharmaceutical approaches involve specific modulators and neurotransmitters that address the psychological adversities associated with the children’s exposure to traumatic events (Katz, 2019). In conclusion, both treatment approaches are crucial for the welfare of unfortunate children.

Are Parents Aware of Their Children’s PTSD?

Over the past many decades, there have been cases where parents have been surprised to learn that their child has had PTSD. Most parents observe a child’s behavior and classify them generally as quiet, emotional, rude, or high tempered (De Young & Landolt, 2018). Many of these parents are not aware that these traits may as well be an indication of PTSD. This study, therefore, aims at determining the level of knowledge parents have and involvement in mental health status of their children. Some of the questionnaires and interviews in this study will seek to obtain information that answers this phenomenon. Data obtained will help medical practitioners and child psychiatrists stipulate relevant guidelines and recommendations and inform government policy of prevention and treatment protocols.

Methodology

The extensive use of self-administered questionnaires is a suitable tactic to gain insight into the issue regarding PSTD in children. Such tools as interviews and self-administered questionnaires are more applicable to adolescents. Therefore, due to their high levels of responsiveness and impartiality, parents are among the most valuable interview and survey subjects. As a result, given the research’s emphasis on school-aged children, the study’s methodology will include both qualitative and quantitative research approaches. The study will focus on evaluating parents’ perceptions of children’s mental state and their awareness of PTSD among children. Additionally, the answers of adults will be analyzed in relation to family history of PTSD and current household situation.

Participants

In order to achieve the highest level of responsiveness and credibility of results, participants from a trusted circle of people were selected. Ten white adults participated in the questionnaire with children between the ages of 10 and 18. The participants were both male and female in order to gain insights and perceptions from representatives of both genders. Consequently, 30% of participants were male, with the remaining 70% being female. The age of participants ranged from 35 to 65 years old.

The selected individuals were reached via e-mail, containing an elaborated explanation of the research, the objectives of the study, and the content of the questionnaire. The participants provided full consent and agreed to provide sincere answers to help achieve reliable results of the study. The survey provided the participants with ten questions in order to determine whether they were aware of their children’s mental health conditions. For the sake of simplicity and convenience of the participation in the questionnaire and collection of the results, a platform, specifically Google Forms, was utilized.

Research Design

The researcher views the mixed methods approach as appropriate for this study due to the following qualities.

- It ensures that the findings of the study are focused on the experiences of the participants.

- It improves the accuracy of the study results.

- It accommodates all the variables of the study.

- It offers the best utilization of resources.

- It consumes the least time compared to other methods.

- It involves the collection of two types of data at the same time (Malarbi et al., 2017).

Questionnaire and Interview

The survey included the following questions to help ascertain whether the caregivers in Kern County and other American regions are aware of their children’s exposure to the secondary PTSD:

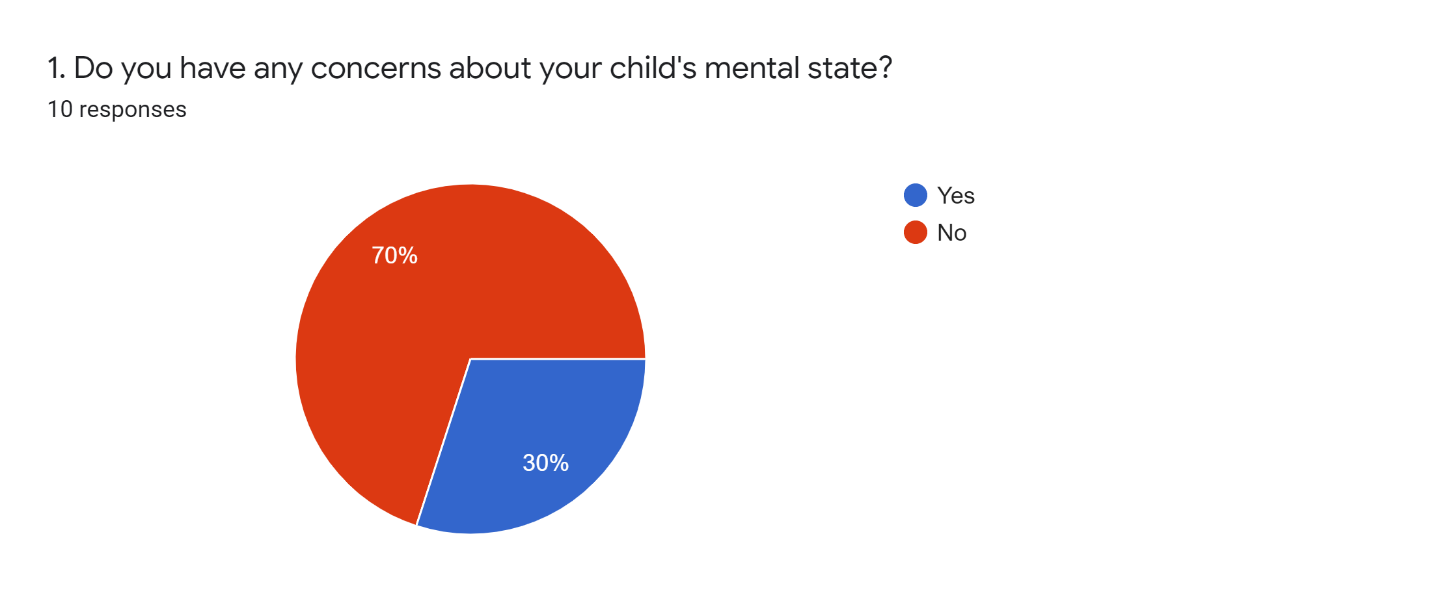

- Do you have any concerns about your child’s mental state? Why?

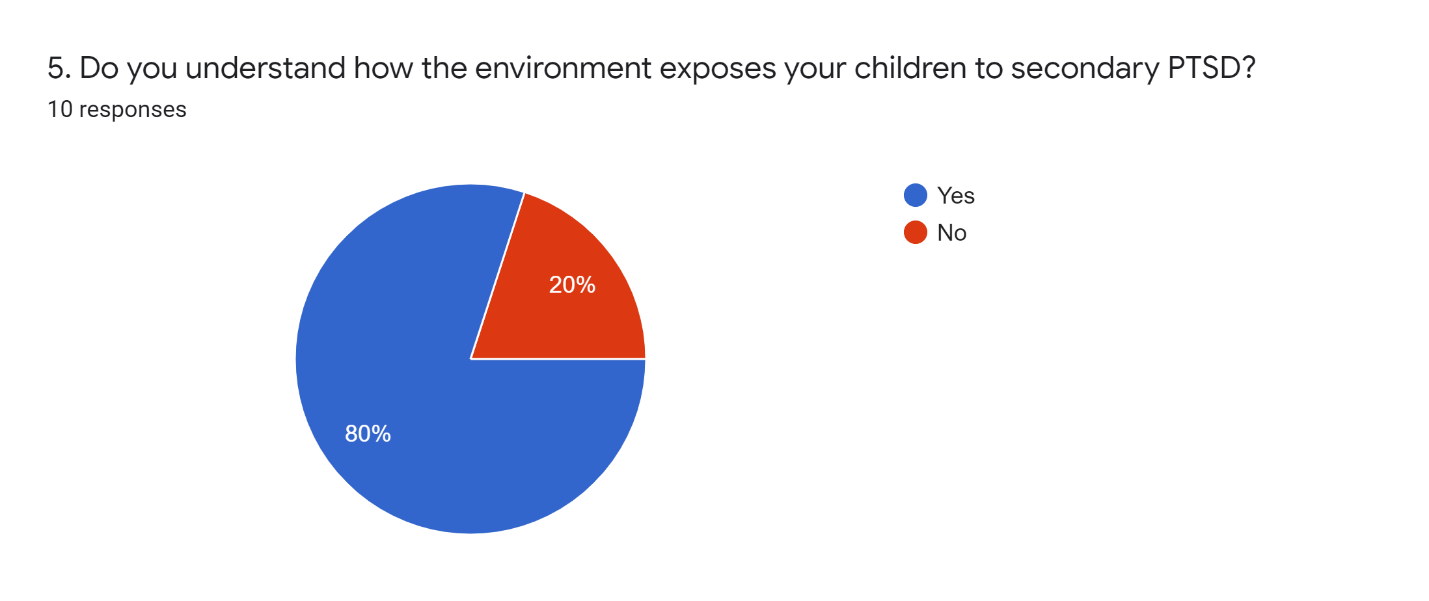

- Do you understand how the environment exposes your children to secondary PTSD?

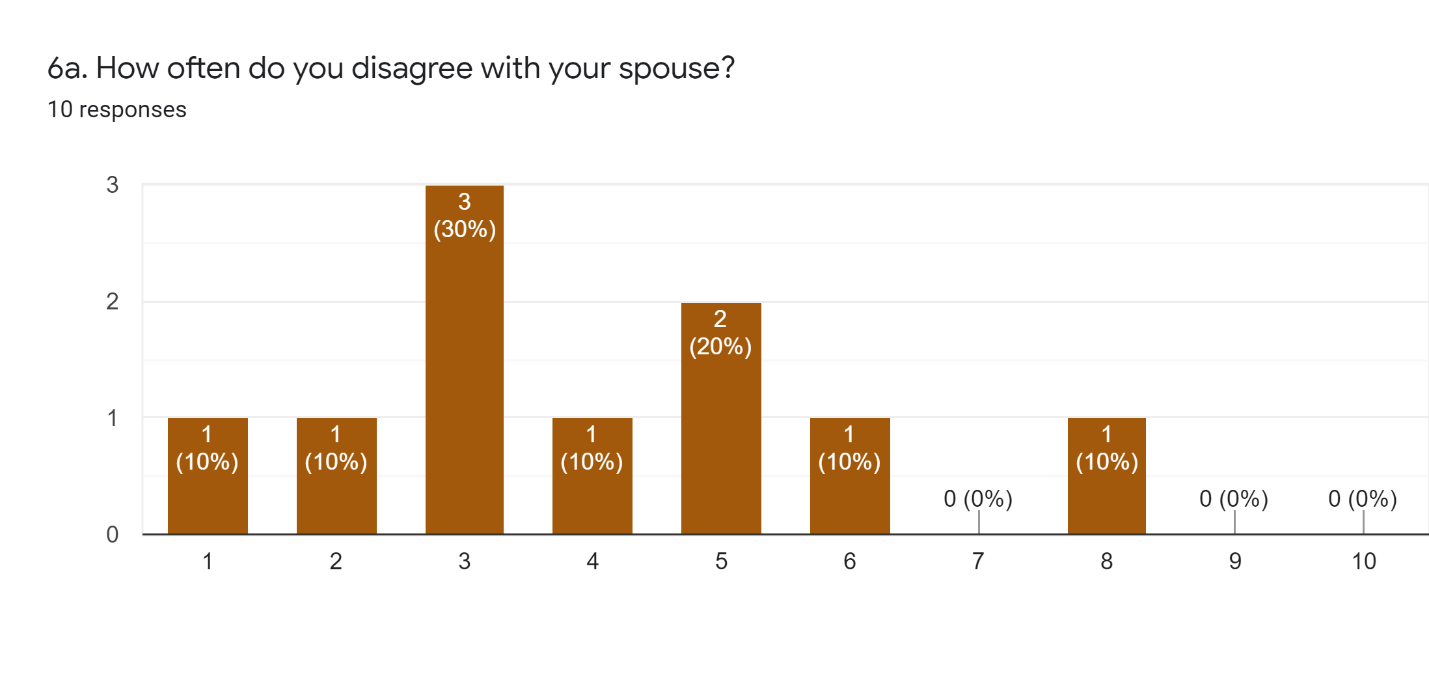

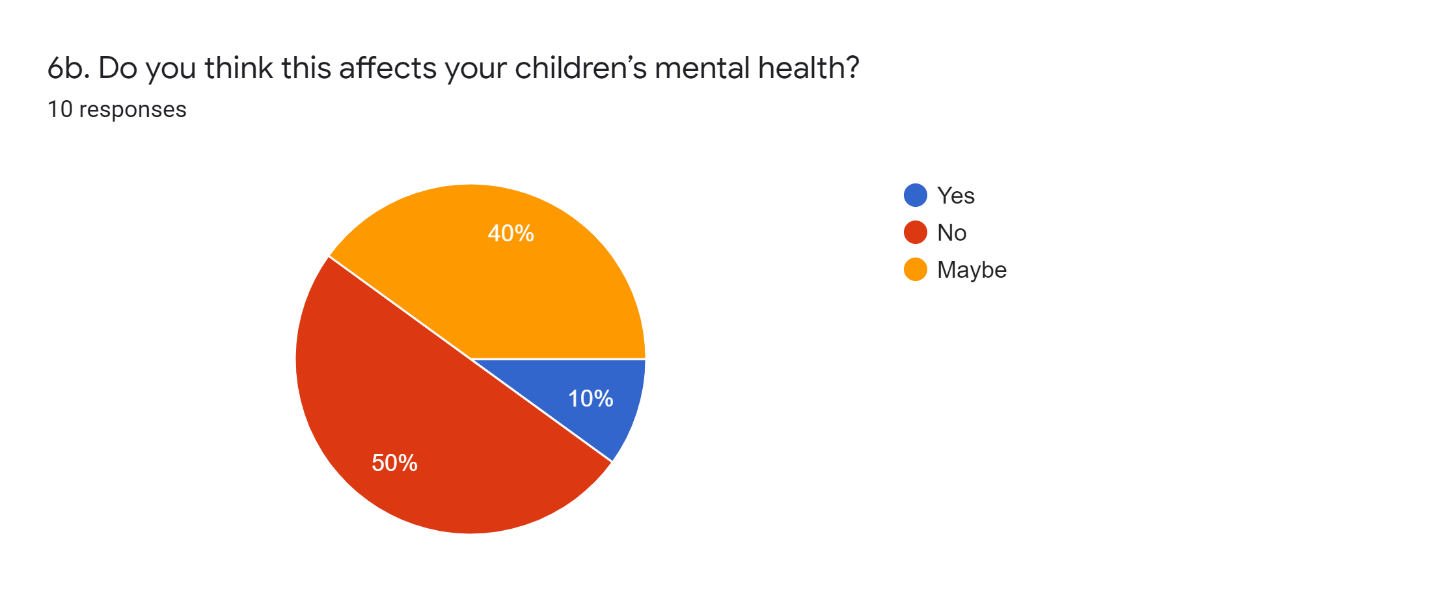

- How often do you disagree with your spouse? Do you think this affects your children’s mental health?

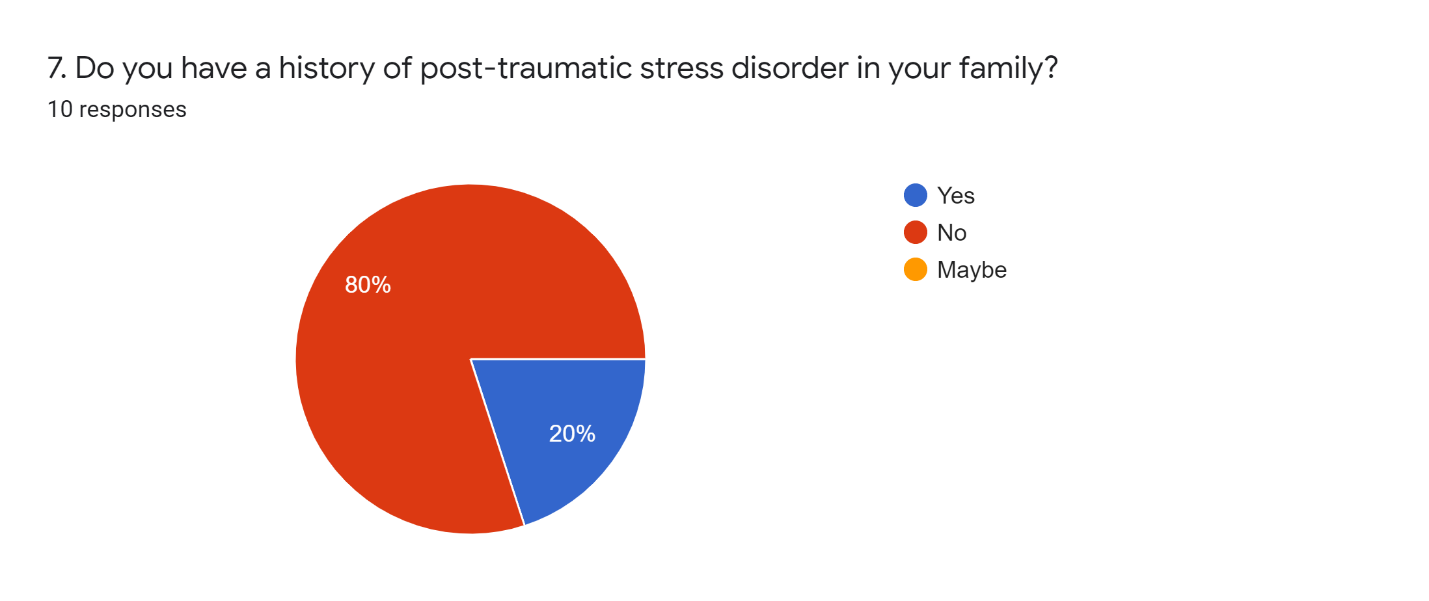

- Do you have a history of post-traumatic stress disorder in your family? Have you ever been worried that your children might develop the same undesirable conditions?

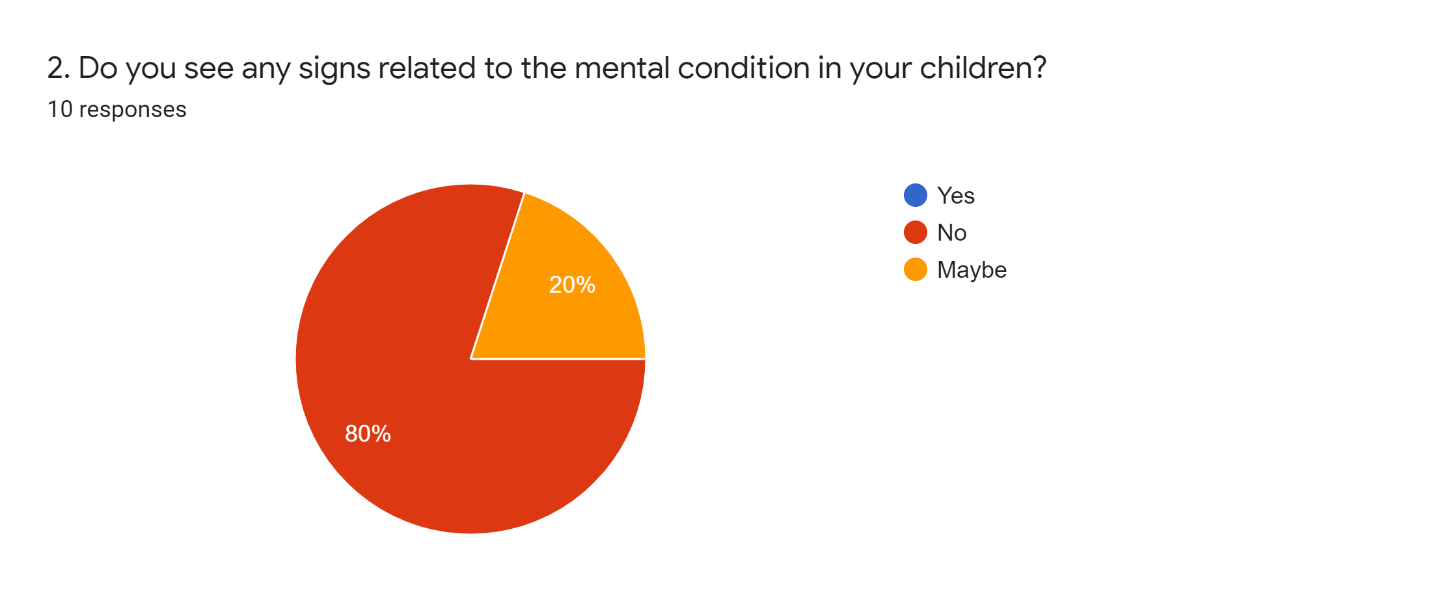

- Do you see any signs related to the mental condition in your children? What measures have you taken to ensure that your child does not fall victim to undesirable mental disorders?

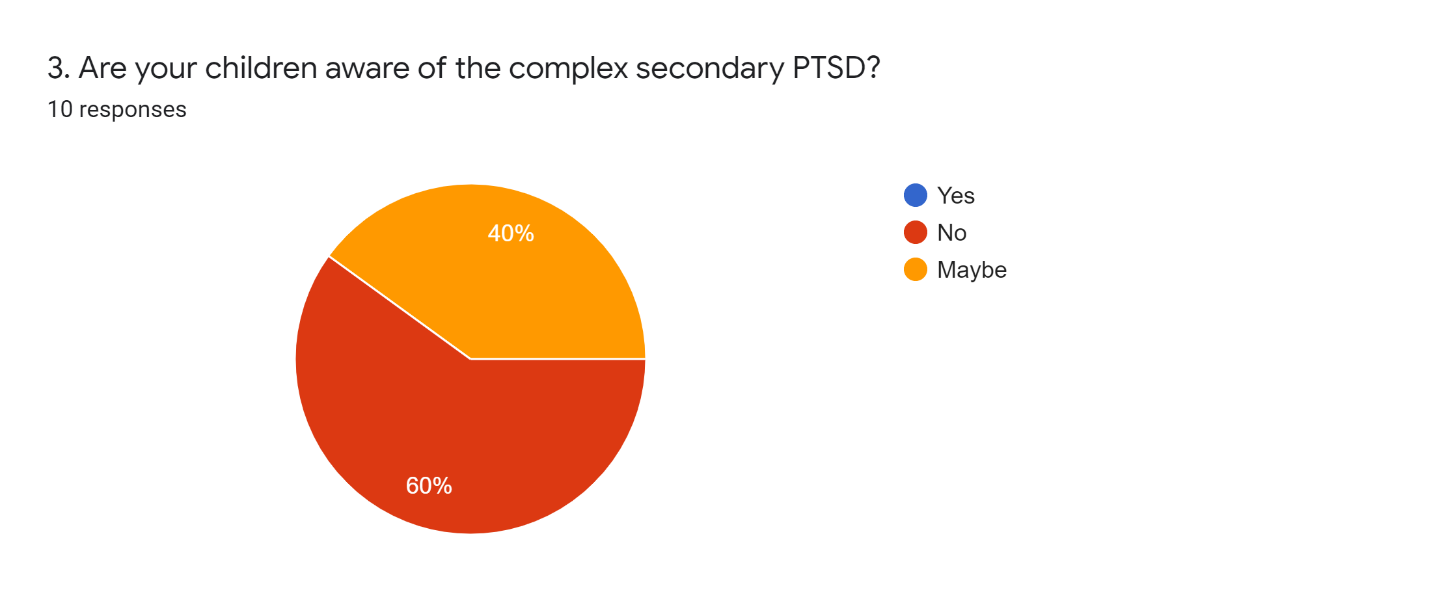

- Are your children aware of the complex secondary PTSD?

- Do you think your children are proud of your parenting strategy? Do your approaches safeguard their mental welfare?

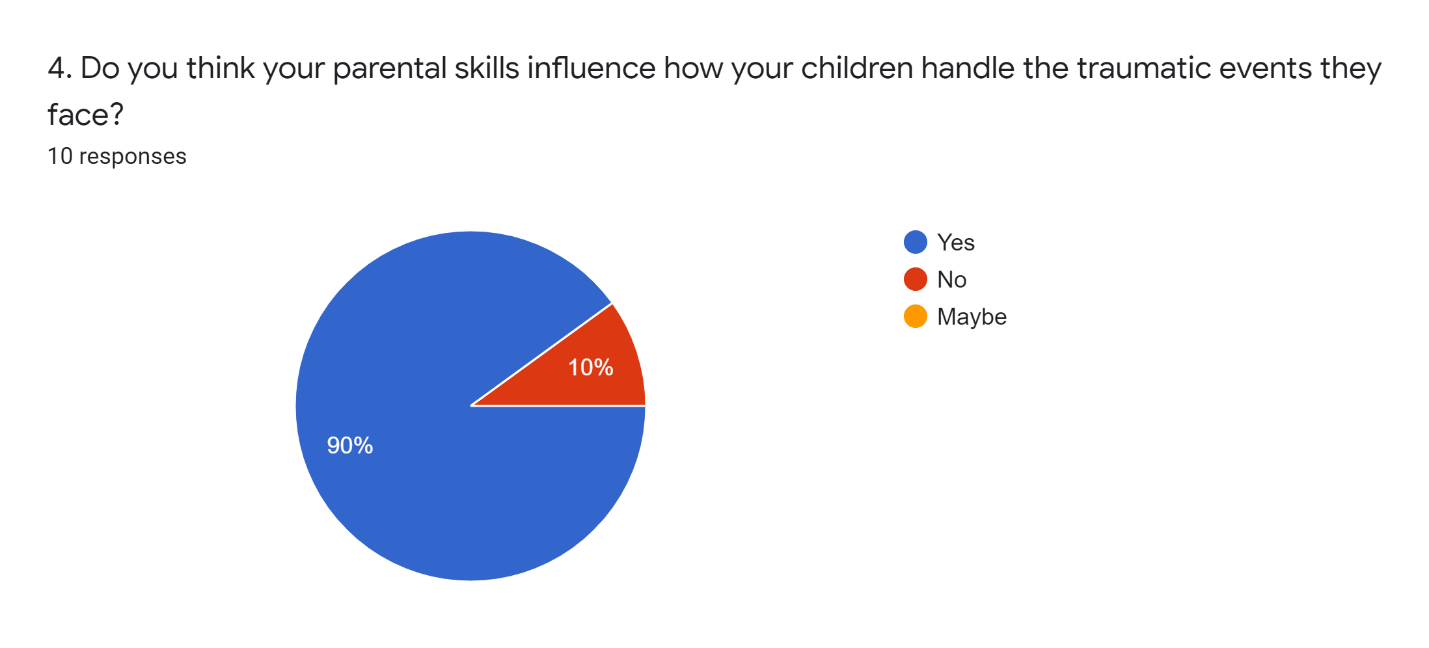

- Do you think your parental skills influence how your children handle the traumatic events they face? Can you support your argument?

- Do you think your children are optimistic about achieving their future goals? Are you sure you are motivating them to maintain their focus despite their interaction with traumatized persons?

- How do you feel about the need for regular screening and treatment of mental health conditions to reduce PTSD?

After collecting the data from the respondents, the researcher will use triangulation to analyze the data and provide recommendations to reduce the children’s risk of secondary PTSD. Thus, incorporating qualitative and quantitative research approaches would guarantee that the study efforts to enhance understanding secondary PTSD are successful (Shannonhouse et al., 2016). This research study will endeavor to guarantee the professionalism and qualification of the entrusted mental health specialists by ensuring an in-depth understanding of the complex secondary PTSD.

Results

Qualitative Findings

Based on the research conducted, several qualitative findings were identified. According to the previous studies on the issue of PTSD among children, childhood maltreatment and early developmental stresses have been linked to an increase in psychological and medical difficulties in children. Medical experts believe that genetic information and interaction with someone who has acute PTSD are important factors to the condition. Furthermore, interactions with a troubled individual may affect the recipient’s mental wellbeing and possibly trigger the condition. Trauma symptoms can vary in intensity from moderate to severe. Insomnia and eating disorders such as anorexia or bulimia are among the less severe symptoms. Stress, anxiety, and negative socioemotional changes, on the other hand, are extreme symptoms. Lastly, according to the studies, many parents are not aware of their children’s symptoms or mental state.

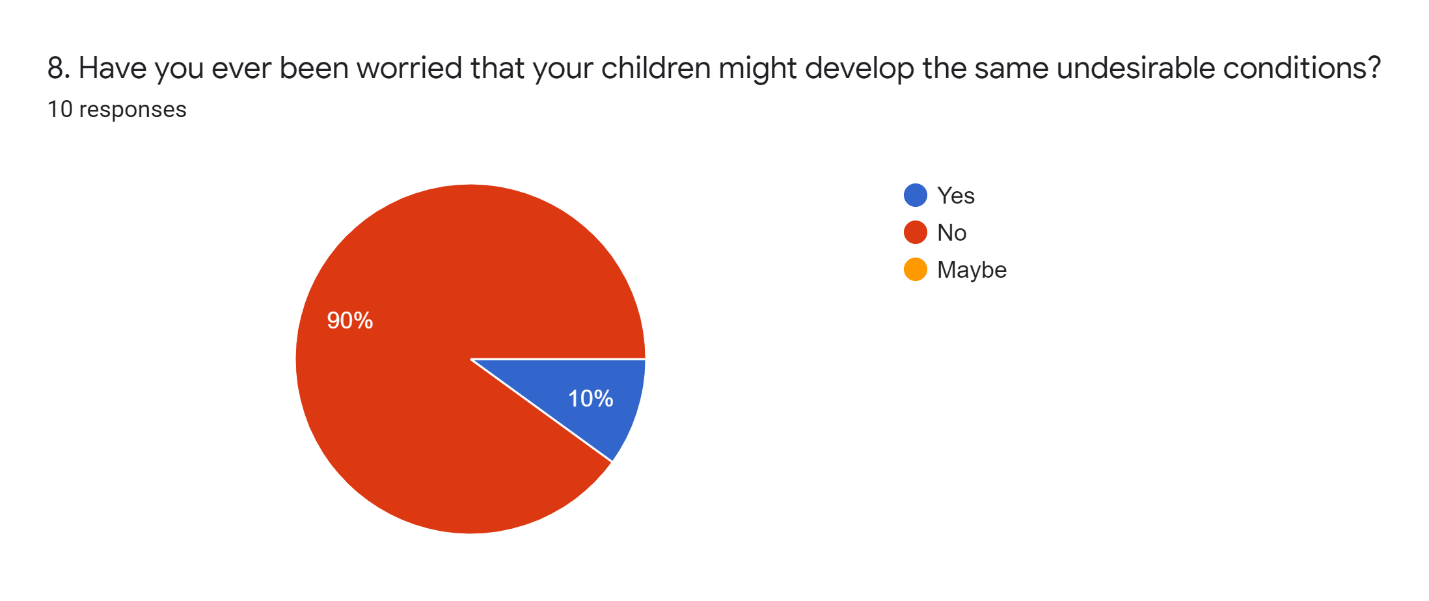

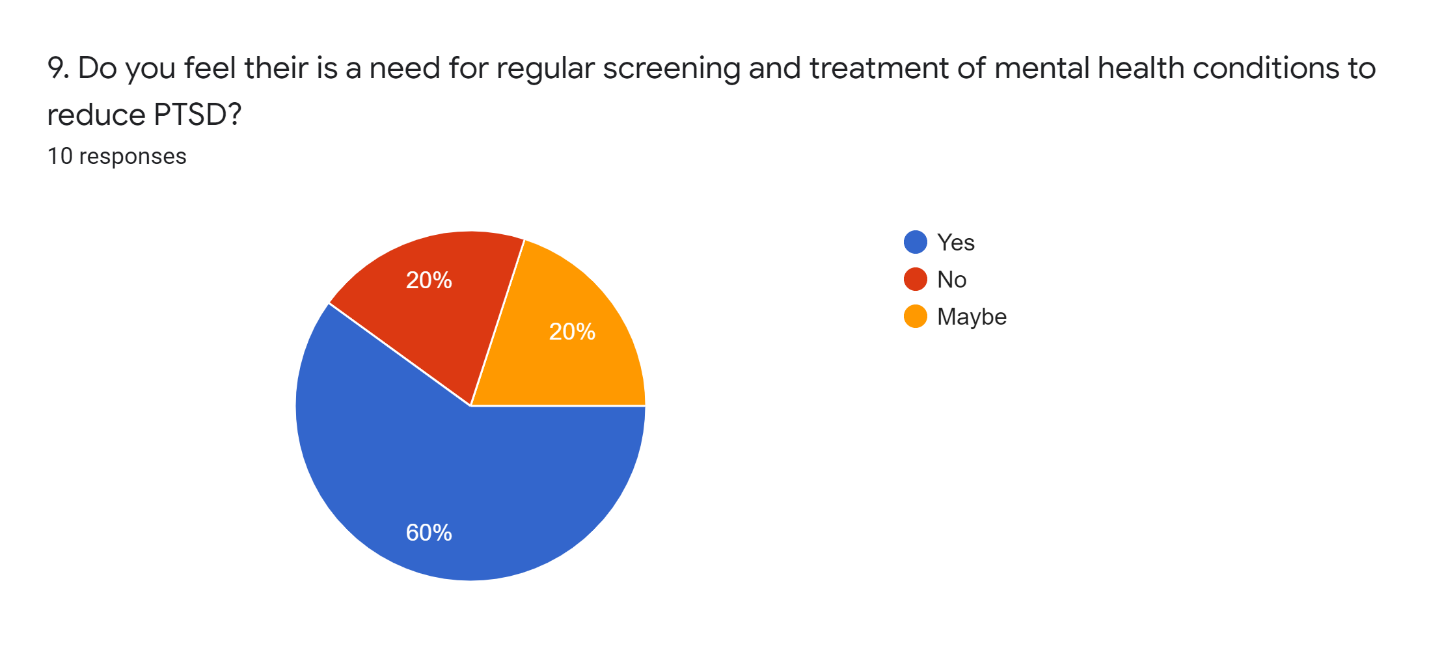

Quantitative Findings

As for the quantitative findings, the questionnaire revealed that at least 70% of the respondents have no concerns about their children’s current mental state. Moreover, more than half of the respondents did not contribute to their children’s awareness of secondary PTSD. However, the majority of parents agreed with the point concerning the influence of external factors on the condition of children. Though disagreements with spouses do not often occur in the families of respondents, and there are mild traces of PTSD in the family, 60% of participants agree to the significance of regular screening and treatments to reduce the levels of the condition.

Hence, both quantitative and qualitative results showed that most parents do not recognize psychological changes and mental state problems of children. According to the data provided by the studies, most of the secondary PTSD conditions are the results of constant stress and anxiety caused by the interactions with a troubled individual, either from family or other circles. However, according to the result of the questionnaire, most respondents do not have a troubled situation in households which allows them to believe in the absence of mental issues in their children.

Discussion

With the help of the respondents, it became evident that the issue of PTSD among children deserves more attention. According to the findings from the previous studies and empirical results provided by the questionnaire, there was a possibility to build a link between PTSD and parental influence. While most of the respondents disagreed with the statement concerning the correlation between disagreements with spouses and a child’s psychological condition, the parent agreed with the influence of their parental skills on the mental health of their offspring. As a result, the findings support the scholarly research and prove that, though the majority of parents do not have any concerns about their children’s mental state, they feel strongly about regular screenings and the correlation between societal influence and psychological conditions of the youth.

Limitations

The empirical results reported herein should be considered in light of some limitations. The first limitation of the study concerns the sample bias. In the conducted survey, which served to acquire the research results, only selected individuals from a trusted circle were asked to participate. As a result, there was a limited ability to gain access to a wide geographic scope of individuals from various backgrounds. In this case, the people who responded to the survey questions were not truly a random sample.

Another limitation of the study concerns an insufficient sample size for statistical measurement. The results of the questionnaire were provided by ten individuals, which may be considered insufficient to gain precise insight into the issue. A greater number of participants was required to guarantee that the results provided by the survey were considered representative of a population and that the statistical results could be extended to a broader population. As a result, a lack of participants could make it difficult to find significant relationships in the data.

Directions for Future Research

As for directions for future research, the first direction concerns the scope of the sample. In order to acquire the valid results of the research, there is a need to recruit respondents from various backgrounds. Individuals from different regions could provide answers which could help set the average variable. Additionally, it is necessary to include more observable parameters to complement questionnaires. For example, to fully observe the issue of PTSD among children, it would be helpful to interview children. As a result, the scholars will be able to estimate concrete statistics and obtain more trustworthy and objective data from the surveys.

References

Akinsulure‐Smith, A. M., Espinosa, A., Chu, T., & Hallock, R. (2018). Secondary traumatic stress and burnout among refugee resettlement workers: The role of coping and emotional intelligence. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 31(2), 202-212.

Cloitre, M., Brewin, C. R., Kazlauskas, E., Lueger‐Schuster, B., Karatzias, T., Hyland, P., & Shevlin, M. (2021). Commentary: The need for research on PTSD in Children and adolescents–a commentary on Elliot et al. (2020). Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(3), 277-279.

De Young, A. C., & Landolt, M. A. (2018). PTSD in children below the age of 6 years. Current Psychiatry Reports, 20(11), 1-11.

Garza, K., & Jovanovic, T. (2017). Impact of gender on child and adolescent PTSD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 19(11), 1-6.

Grant, B. R., O’Loughlin, K., Holbrook, H. M., Althoff, R. R., Kearney, C., Perepletchikova, F., & Kaufman, J. (2020). A multi-method and multi-informant approach to assessing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in children. International Review of Psychiatry, 32(3), 212-220.

Hamblen, J., & Barnett, E. (2018). PTSD: National Center for PTSD. Behavioral Medicine, 366-367.

Katz, S. (2019). Trauma-informed practice: The future of child welfare. Widener Commonwealth. L. Rev, 28, 51-83.

Kellogg, M. B., Knight, M., Dowling, J. S., & Crawford, S. L. (2018). Secondary traumatic stress in pediatric nurses. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 43, 97-103.

Malarbi, S., Abu-Rayya, H. M., Muscara, F., & Stargatt, R. (2017). Neuropsychological functioning of childhood trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 72, 68-86.

Marsac, L. M., & Ragsdale, B. L. (2020). Tips for recognizing, managing secondary traumatic stress in yourself. A.A.P. News. Web.

Meiser‐Stedman, R., Smith, P., McKinnon, A., Dixon, C., Trickey, D., Ehlers, A., & Dalgleish, T. (2017). Cognitive therapy as an early treatment for post‐traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial addressing preliminary efficacy and mechanisms of action. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(5), 623-633.

Menschner, C., & Maul, A. (2016). Critical ingredients for successful trauma-informed care implementation. Trenton: Center for Health Care Strategies, Incorporated.

Rezayat, A. A., Sahebdel, S., Jafari, S., Kabirian, A., Rahnejat, A. M., Farahani, R. H., & Nour, M. G. (2020). Evaluating the Prevalence of PTSD Among Children and Adolescents After Earthquakes and Floods: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Psychiatric Quarterly, 1-26.

Sachser, C., Berliner, L., Holt, T., Jensen, T., Jungbluth, N., Risch, E., & Goldbeck, L. (2018). Comparing the dimensional structure and diagnostic algorithms between DSM-5 and Psychiatry. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 27(2), 181-190.

Secondary Trauma Effects on Teens and Young Adults. (2020). Sandstone Care. Web.

Secondary traumatic stress. (n.d.a). Administration for Children & Families. Web.

Secondary traumatic stress. (n.d.b). The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Web.

Shannonhouse, L., Barden, S., Jones, E., Gonzalez, L., & Murphy, A. (2016). Secondary traumatic stress for trauma researchers: A mixed methods research design. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 38(3), 201-216.

Sherman, M. D., Gress Smith, J. L., Straits-Troster, K., Larsen, J. L., & Gewirtz, A. (2016). Veterans’ perceptions of the impact of PTSD on their parenting and children. Psychological Services, 13(4), 401-410.

Smoller, J. W. (2016). The genetics of stress-related disorders: PTSD, depression, and anxiety disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41(1), 297-319.

Van Ee, E., Kleber, R. J., & Jongmans, M. J. (2016). Relational patterns between caregivers with PTSD and their nonexposed children: A review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(2), 186-203.

Yue, J., Zang, X., Le, Y., & An, Y. (2020). Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Current Psychology, 1-8.

Appendix A

Survey Response

Appendix B

Survey Data